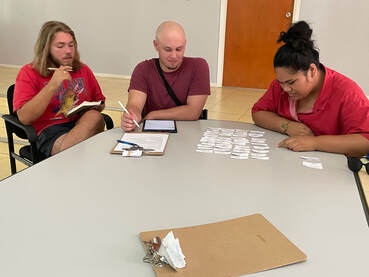

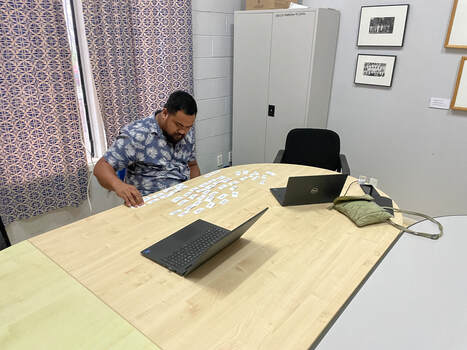

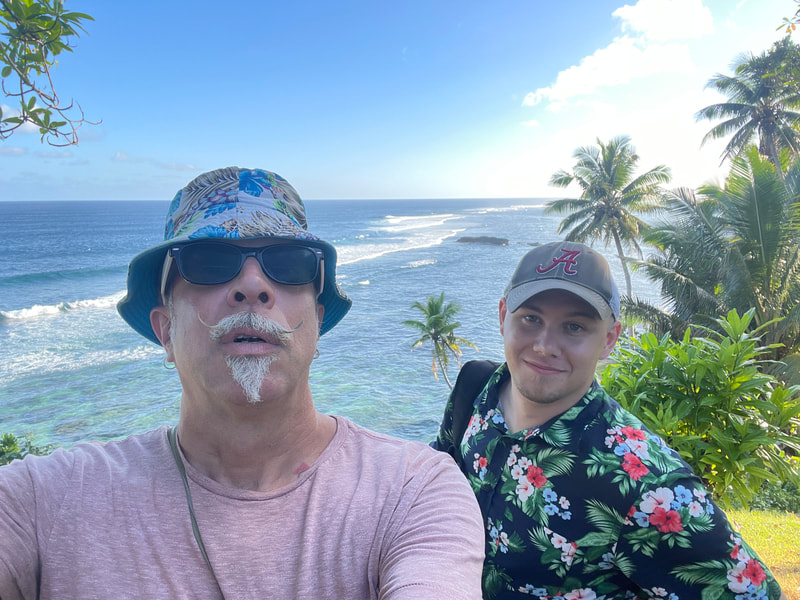

Thursday, July 20, 2023 Leota sees us onto the ferry to American Samoa. Leota sees us onto the ferry to American Samoa. The scheduled time to go to the ferry for the overnight ferry to American Samoa was something like 6pm. I was originally going to drive there and leave our rental in the parking lot. Leota didn't feel comfortable leaving us to our own devices nor with us leaving our car in the lot, so he volunteered to drive us there and keep watch over our car at his house. He didn't think we needed to be there at 5, as I suggested, to ensure we weren't late. He said we could be there at 8pm and be fine. He didn't think the ferry would leave before 10 or 11pm. I was naïve, and Leota would turn out to have been optimistic. When we told people we were taking the ferry to American Samoa, we got a variety of reactions. Some were impressed by our mettle; ours warned us of the weather and conditions. Many Samoans have never taken the ferry to American Samoa. I think it is a bit of a status thing to take the flight over the ferry, but it is also a time and comfort thing. The financial savings are not worth the trouble, and we would've paid more to avoid it if we could have. he wait for the ferry while they loaded took several hours in a crush of humanity. No one seemed to know how the loading worked, so everyone kind of crowded in, us included. We crowded near the front until someone finally told us how to read our ticket, and we realized we would be loading among the last groups, so we got out of the way and sat down. Families were stocking up on food for the trip, buying meals from vendors at the station. We should have done the same. At any rate, we finally boarded around 8:30 or 9. We initially thought we'd have to sit on the floor of the cafeteria, but we ultimately found seats. Josh had been worried about getting seasick and purchased Dramamine from a pharmacy in Apia. We took the meds and slumped in our seats. Grant went wandering. I think I woke up before we even left and eventually got down on the floor with everyone else to try to sleep. The storm kicked up before we left and buffeted us all the way there. The boat continually went up and slammed down, up and slam down. It was jarring and relentless, but I never felt unsafe inside the cabin. The boat never tipped side-to-side. Just the steady up and SLAM. I thought the only entrance to our cabin was the one on the far side of the room, as people kept climbing over sleepers throughout the night to reach it. But it turned out there was another door right behind us that just wasn't being used, except by Grant, who found it eventually during his wanderings. Josh and I didn't leave the cabin we were in, trying to stay settled, not vomit, and get some sleep. I did in fact sleep on the floor most of night, nodding in and out of consciousness. Most of what I know that went on comes from Grant and Josh. People were laying over every available floor space, so I had no compunction about sticking out into the aisle. My main memory is of being stepped over repeatedly throughout the night. I heard the coughing, but I didn't realize it was seasick vomiting. Apparently, a guy behind us was just throwing up on the floor in front of him as he lay trying to sleep. Grant spent the night wandering the ship and surfing the storm up top with a bunch of Samoan guys he befriended. He was sopping wet when he finally came down. Because Samoa is now at the beginning of the day and American Samoa at the end, the trip lasted about 6 hours, and we landed the morning of the day we'd left. Very confusing. I am time-zone challenged under the best of circumstances--this was breaking my brain a bit. I had made reservations for us at Sadie's By the Seashore, one of two decent hotels in American Samoa. I tried to book the Tradewinds, the other decent hotel, which is near the Olaga offices in American Samoa, but they were booked up. Sadie's had vacancies, and was right next to the ferry terminal, so we were set.  Here we are at Sadie's getting a meal & multiple Cokes with ice. Stupid. You'll be paying for that ice for a few days, dummy. Here we are at Sadie's getting a meal & multiple Cokes with ice. Stupid. You'll be paying for that ice for a few days, dummy. When we walked out, I looked around and thought I knew where we were. We'd go to the right, and Sadie's should be right there. We walked for about 15 minutes, and I said, "wouldn't it be funny if we walked the wrong direction?" We had a running joke of some sort, so we kept walking, but after another 15 minutes, I questioned my own impeccable sense of direction and asked a guy coming out of a store. He pointed the direction we were walking, so we thanked him and kept walking. After nearly an hour, we reached the tuna canneries, which I knew were well beyond our destination. I flagged down a cab, who gave us a ride to Sadie's for $10. It was all the way back around Pago Pago Harbor from where we'd come, just a few steps to the left of the ferry. He was a retired Filipino-Samoan schoolteacher, born and raised in Samoa. I didn't have the bandwidth to chat, but Josh and Grant kept up the banter for us. Grant was fading however. We got ourselves checked into Sadie's early and crashed out in our room. We'd tried to reach our families back home to let them know we were safe, after ominously texting "taking the ferry in a storm" before an extended radio silence. However, we were too fried to move immediately and crashed out in our room for a few hours. Then we got up, had some food, drank some Cokes over ice that would later give us serious traveler diarrhea, and sent out emails to try to make arrangements for Friday. I reached out to Joe Ioane from Off Da Rock Tattoos, who was our main collaborator and data collection site back in 2017. I'd had to leave a week early that summer due to a family emergency and did not say goodbye properly. I also got in touch with Joshua Naseri, who runs the Olaga programs in American Samoa and made arrangements to meet for a happy hour beer or three tomorrow. Friday, July 21 Riding around Nu'uuli & Tafuna in the back of a pickup. Riding around Nu'uuli & Tafuna in the back of a pickup. We were at lunch in the restaurant at Sadie's when I see someone familiar. I keep looking and keep looking. I finally decide that it's Leuila Ioane, Joe's wife, and the person with his back to us therefore is probably Joe. I'd told him in my message that we were staying at Sadie's, and he'd responded, so if he was here, wouldn't he look us up? Apparently not. I finally went up to them, and indeed it was. Joe and Uila are a powerhouse couple. They're both Army Reserve, fitness buffs, and driven entrepreneurs. When we were there in 2017, Joe was building a workshop attached to the tattoo studio for Off Da Rock Fashions, Uila's business. She designed cloths, and they had a team of seamstresses making them. I have two great handpainted ties. Joe and Uila and their kids (four now, two more since last time) all look like rock stars modeling her designs. Anyway, I ask Joe if he can recommend a rental agency, as I'd decided we really did need a car and was about to go try to rent one. Instead, Joe offered to rent me one of his extra cars for a flat rate if I could drive manual. I definitely prefer island cars from friends when I can get them. Cuts right through the bullshit, and I trust Joe. Unfortunately, neither Josh nor Grant had any experience with stick shifts, so I would end up doing all the driving. After lunch, we jumped into the back of Joe's truck and accompanied him on errands until he got back to his neighborhood in Ottoville. He hooked us up with the car, and I gave Josh and Grant a brief tour of Leone until we realized Grant was flagging. So we went back to Sadie's. Grant took a nap, and Josh and I went to meet Joshua Naseri in the restaurant. We had a few beers with Josh and told him about our project in person. I'd been emailing back and forth, but this was the first time we got to meet in person, and the project is much easier to explain in person. Furthermore, he was really intrigued by the methods. His team would be able to try out data collection over the weekend, then we'd debrief on Monday and go from there. We were thrilled. The Olaga team were locals, so they'd be able to collect data much more easily than we could. One of the adjustments that we'd all agree should be made it that we'd pay more in American Samoa. I don't think I've mentioned the payment, but it was made very clear at the beginning of our data collection that anything but cash would be seen as colonial and paternalistic. In Samoa, we were paying $25 tala per participant for pile sorts, which seemed like a reasonable amount to our collaborators and participants. Given the exchange rate, that would be around $9.33 USD, which is both a ridiculous amount and too low for participant reimbursement. We ended up paying $25 USD in American Samoa because it felt equivalent to people, even though it wasn't and everyone acknowledged it. Weird. Time to convalesce and watch Women's World Cup Soccer, which was being played in New Zealand and Australia, so near our current time zone. Josh and I are sports fans and looked forward to having something to watch when we weren't out and about. Grant was still sleeping and would be down and out for most of the next two days with a fever. I was paying for that ice non-stop all day. Good times. Tuesday, July 18, 2023 University of Alabama researchers Josh Lockhart and Grant Pethel administering pile sort activity at National University of Samoa. University of Alabama researchers Josh Lockhart and Grant Pethel administering pile sort activity at National University of Samoa. Josh Lockhart, Grant Pethel, and I went down to the shipping terminal to buy ferry tickets for American Samoa. We were planning to travel to Tutuila to collect data. Tutuila is American Samoa's main island, the Manu'a Islands the other. I had planned to go to Ta'u in the Manu'a Islands of American Samoa as well, but it was impossible. Flights among the islands are touch and go. The second airport in Samoa just reopened in July, so more flights had become available. However, the bottleneck of people traveling back and forth to see family was such that they were booked up for several weeks. The only way to travel to American Samoa during the six weeks of the field season without having known ahead of time was to travel by ferry. This would be rather difficult because our return flights to the US were out of Samoa. Had I planned better, we'd have flown into Samoa and out of American Samoa and saved ourselves considerable stress. We had gone directly to the ferry the day before after getting back from Savai'i, but Josh did not have his passport with him so we were not able to make the purchase. We planned to come right back with the passport but were tired and by the time we got back and didn't want to drive back downtown. We would have bought the wrong tickets if we'd done that because of the time zone issues. We would have to buy a ticket that would leave on Friday from Apia at around 8pm and arrive in American Samoa on Friday around 2am. The return ferry would leave American Samoa around noon, and that would get up back in Apia on Saturday around 2am. It's very confusing to me. We'd chatted with our host, Lai, and he'd told us which tickets we needed to buy. So we did that and then went to the CSS offices to conduct some pile sorts of participants we had recruited. For lunch we went to Burger Bill's. We thought it was funny and kept accidentally ending up in their parking lot for some reason and had a hankering for a burger or something and went there. Bad idea. I have not been a fan of much restaurant fare in Samoa, but this was gross. I got a mushroom swiss burger for some reason. I should have known better because my first job was at Hardee's, and Hardee's had a mushroom swiss burger that I found gross then when I liked fast food (working at Hardee's soured me on that place forever). Burger Bill's burger was similar, so I left it unfinished. Grant and Josh had underwhelming experiences as well. Wednesday, July 19 Left tray: pulasami, oka, fish is coconut milk; right tray: chicken, pork, yams, seaweed, cucumber-tuna, and bread? Left tray: pulasami, oka, fish is coconut milk; right tray: chicken, pork, yams, seaweed, cucumber-tuna, and bread? The best food we have eaten in Samoa has been what people have served us at their homes, for the most part. I'm not a fan of the curries I've had there. They are simply flour based sauces, I think. Fortunately, we were eating at Leota's for dinner, which would include the #2 pig. He also promised to make a couple versions of Oka (fish in coconut milk and lime juice), which is one of my favorite Samoan dishes. In the meantime, we ran errands and tried to meet up with Su'a Alaiva'a Sulu'ape. We'd been popping in, and Ata finally gave me his cell number and told me to call him. I did but just got voicemail. I also texted. We had arrangements to meet that day but could not nail the time down. Su'a will often roll in a few hours after the arranged time, but he is Su'a, so no one says a word. However, we were on a schedule, so we could wait an hour or so but then would have to jet. We sat watching Junior, and he introduced us to the family he was working on. It was the son/nephew of the Nu'uuli fautasi team in American Samoa. I told Josh and Grant how important these guys are, and they were very friendly and receptive. They live in Pago Pago, so we made arrangements to meet up with them the following week for data collection when they'd be back home and we'd be over there. We went over to Leota's around dinnertime and met his family. This included his wife, young daughter, and baby son. His wife is a teacher a Samoa College. They also live with Leota's brother and three cousins, who go to university and help with the kids. Basically, all land is family land, and they are from Savai'i. So when they are in Savai'i, they obviously have places to stay as any kid would going home. But when they are in Apia, this is an extension of their village, giving them a family to stay with in Apia too. Leota tells me that from now on, I will stay with them and in the village when I am in Savai'i. Leota's mother bought the property they have in Apia, and she is buried there. This was a big deal for Leota and a decision he is unsure was the best political move for him. He aspires to be High Chief some day, and he certainly has the character and aptitude for it in all the best ways. His mother was an important chief, and she should have been buried on the traditional family land, rather than a new piece of property on another island. However, Leota was so close to his mother that he could not bear to be separated from her, so he pleaded with the High Chief to be allowed to bury here in Apia. In previous years, I've puzzled about the Samoan custom of burying family in the front yard. This year we got a thorough education about it from Leota. According to Leota, fa'alavelave are more important than the Christian holidays, even though Samoans are very Christian. Fa'alavelave are gift-giving celebrations that accompany important village events, such as weddings and funerals. Funerals are as lavish as weddings for Samoans, with family flying in from all over the world. The celebration of the deceased lasts several days and includes lots of event planning. We witnessed one next door from our Air'B'n'B that lasted several days. They had multiple Taula party tents set up and were outside cooking in the traditional style near the edge of property near us. There were ceremonies we caught glimpses of in the distance, and there were crowds of people.  Research teach with Leota's family in Apia. Research teach with Leota's family in Apia. Like weddings, professional photographers capture it all on film, and Leota showed us the video of him wailing atop his mother's coffin. Fa'alavelave are important and expensive, but Samoans don't think of money as something that needs to be squirreled away for personal use. They are a communal-oriented culture, especially compared with my own midwestern US background. In Samoa, everything is owned by the family and village, not individuals, so money flows through the family and village and is not kept by individuals. For the most part. Banks accommodate this; fa'alavelave loans are easy to get, have no/low interest, and you can get multiple fa'alavelave loans even if you haven't paid off previous ones, because of the value these events have in the culture. Burying family in the front yard is very important in Samoa. By doing that, family remain close. They are buried in the front out of respect, and the size and design of their monument often indicates their status in life. Untitled people may have unmarked graves in the yard but are still with family. In Savai'i, Leota pointed out several graves around the monuments that we had thought were simply landscape decor. The cemeteries I've photographed in previous posts are often graves of displaced, foreigners, or those whose family land is gone. There is one such near NUS. Leota regaled us with these stories, and he and his family served us dinner and entertained us with some ukulele playing and singing. I will have to ask him to teach me a Samoan song next time, as I usually travel with a small stringed instrument to pluck on (uke or stick dulcimer). He family is lovely and daughter is charming, and the food was fantastic. Leota's oka is spot on, and even though there was too much food, I ate two servings of oka. Leota explained to us that their tradition of hospitality requires that they serve guests and make sure they are satisfied and retired because they eat. He told us this in Savai'i, which is why he was always sitting before us as we ate and never eating himself. So again, he sat before us and talked with us while his wife and cousins brought us food. By this point, Leota felt comfortable giving us friendly cultural advice on how to behave, which we appreciated. He had told us going to Savai'i that humility is the thing. Josh and I would like be seen as flashy because of our hair. Josh has long hair, and I put product in mine and have a somewhat extravagant mustache. Grant had his head shaved, which is seen as simple. So he reinforced that I should be sitting in the middle as the important person. They would bring us a tray of food and extra of everything as soon as we tried to finish a dish. It was a Sisyphean effort to finish a meal because they would refill everything so fast. Fortunately, we had learned from Dionne the trick of at least having a bite of everything and not feeling guilty beyond that. Like money, food flows through the village. It is not wasted if it is not all eaten. It will go to the untitled people serving us later, and what they don't want goes to the pigs or the dogs, and it will replenish itself.  Grant, Leota, me, and Josh outside the RSA, Western Samoa. Grant, Leota, me, and Josh outside the RSA, Western Samoa. We managed to not be completely distended by the end of the meal because Leota wanted to take us out for some beers before we left for American Samoa. So after the obligatory photo of everyone, we went down to the famous RSA. I say famous because apparently it is known as one of the best nightclubs in the South Pacific. I thought this was odd, as there are a lot of clubs popping up around Samoa and American Samoa it seems. However, it turns out this was one of the first, and it is one of the few places a touring band might play if they went to the South Pacific (which I think is probably rare, expect among islanders musicians themselves). Grant is very good at putting himself out there to get the party started. He jumped out on the dance floor and had local women dancing with him. We had a great time with Leota and learned a couple other lessons. He thought it was weird that each of us paid for ourselves going in, and I covered him so didn't notice; but the custom in Samoa is that the first person in a group walking in pays for everyone. And when someone gets a beer, they get one for everyone. I actually had been covering Josh and Grant for most things on our National Science Foundation Grant, but they don't cover nightclubs and drinking, so I'd toggled to the American style of covering ourselves. Having friends there willing to tell us these things has been great. I'm very torn about staying with Leota's family in the future, not because I'm not thrilled by the offer and opportunity. I have an excellent relationship with our hosts Lai and Renon, and I learn a lot from them too. Lai and Leota are both talking chiefs, so they are very knowledgeable about Samoan culture and history.  Grant gets parties started and keeps them going. Grant gets parties started and keeps them going. Leota showed us the genealogy of his family he has memorized and written out. As a talking chief, it is his responsibility to know the family history and names. The titles are passed around to indicate status and lineage in the hierarchy. For instance, the title Leota is an important one in Gataivai and widely used. Several of the chiefs we interviewed were also called by their chief name Leota. I promised not to publish it, but Leota let me take a photo of the genealogy. Leota says he has memorized 72 generations but has not completed his memorizing. He knows ancestors that predate the colonial encounter, however, making me wonder about the validity of the concept of prehistory/history with regard to Samoa. Leota says that Samoans know more about their culture than has ever been written down because it is palagi who write things. Samoans live them. But he is worried that his children will lose access to the truth of their culture through learning to read if the truth isn't written by Samoans for the children to read. Matai are responsible for preserving their culture, so he considers this his mission as a scholar. He says the chiefs don't really value the university education, but they appreciate that it must be done to protect them, and they support Leota in this role. The woman who had been dancing with all of us but especially Grant was a US Customs Officer and was trying to get Grant to continue the party with her friends, but he politely declined and we dropped Leota off and went "home." Monday, July 17, 2023 My gifts from the untitled men of Gataivai. My gifts from the untitled men of Gataivai. On Monday we got up and prepared to leave to catch our ferry. The High Chief asked us to stay for the leaving ceremony or if we could come back for the final ceremony before leaving. It's a ceremony presented by the untitled women, as the 'ava ceremony had been hosted by the untitled men. We had exchanged gifts with the untitled men on Friday. We strolled around the area a bit. I was following pigs around because they reminded me of my chihuahuas! I think I found the #4s, and I decided not to get any closer.  Full breakfast and full lunch together! Full breakfast and full lunch together! Since our ferry ticket was technically for 2pm, the village considered us under their care until we left the island, even though we'd have to leave the village a few hours early to get lined up for the ferry and because we wanted to go to the market beforehand. That meant they wanted/needed to feed us breakfast and lunch, so they brought it to us together. Breakfast was awesome. I was still a little overfull from the day before, so koko aris (cocoa rice), fruit, eggs, and bread were fine. But then they brought "lunch," which included hot tuna and cucumber. After the hot tuna last night, I couldn't do it again. Nope. We had so much food from the 'umu the night before that we had a whole cooked #2 pig and a chicken to take back to 'Upolu. We agreed that Leota would take it back to his house, and we'd all go over there for a Samoan meal before we left for American Samoa later in the week. We took photos with the family before leaving, then stopped to see another star mound on the way to the ferry. This was the most visible mound we'd seen yet. This mound had been cleared off in conjunction with the Centre for Samoan Studies (CSS), and the owner had been advertising it for tourism. But they'd taken the sign down and were no longer maintaining the site, using it as a plantation for taro, coconut, and cattle instead. But Leota stopped by the home of the owner and received permission for us to visit with Leota. Not only was this mound the most visible, the low walls or walkways that CSS archaeologist Greg Jackmond had told us about were clear. They were the most obvious route to the mound, so you are walking on them before you realize what it is and that it's a human-made feature you're walking on.

Sunday, July 16, 2023 Grant Pethel, Josh Lockhart, and I watch Leota prepping food for the 'umu. Photo by Tala Esekielu Lealamanu'a. Grant Pethel, Josh Lockhart, and I watch Leota prepping food for the 'umu. Photo by Tala Esekielu Lealamanu'a. When Grant, Josh, and I woke up in the fale tele at 8 am, we were surprised that we'd managed to sleep so late. We were ushered to a shed in the back where Leota and his family were preparing the 'umu. They'd been up since 6am and had already butchered a #2 pig in preparation. 'Umu is food cooked in an earth or stone oven. It's generally prepared on Sunday for after church. The untitled men prepare the feast to be ready when the family returns. Our 'umu would contain pig, taro, yams, and octopus. It was raining outside, and we could see the neighbors up cooking as well. They had a spigot out back for water and cooked in rigged cookware suspended over a fire in the rain. We at least had a roof for our cooking. Leota had purchased an octopus in the market when he arrived from 'Upolu ahead of us Friday. He was about to prep the octopus when we wandered up. Leota's cousin Kalama seared the octopus on the fire to firm the flesh and make it easier to cut. Leota first cut the tentacles off, then squeezed the ink from the head into a bowl of coconut milk. He cut the entire octopus and all the tentacles into bite sized chunks and put it in the ink coconut milk mixture. Leota then filled taro leaves with octopus and the juice while Kalama held the giant leaf like a bowl, then wrapped it up in foil to seal it. They made probably a dozen of these. Next they prepared the #2 pig. Samoans rate the pigs 1-4 by size. Fours are the biggest and are reserved for fa'alavelave or very special occasions. The pig's viscera had been previously removed. Kalama used a coconut rib folded in half to make tongs and picked up a hot stone from the fire and crammed it inside the pig. He then stuffed a bunch of wet leaves in the fill the remainder of space, but we were told that we do not eat those leaves. I am guessing they either help maintain the moisture inside or they simply keep the stone from falling out. The taro and yams had already been prepared and were in baskets around us. Kalama and his wife Tala pulled the wood off and out of the rocks with help from their son and a young cousin. They then spread the rocks out a square sheet of metal, exposing as many red hot coals as possible. They placed the pig directly on top of the coals, then piled all the taro, yams, and packets of octopus. They covered all of this with fresh taro leaves, then dry taro leaves, then several old mats, and finally an old blanket. This would all cook in about 45 minutes!  Clockwise from left: Saimin, fish, taro, pulasami (taro leaves in coconut milk), pork and chicken, octopus. Clockwise from left: Saimin, fish, taro, pulasami (taro leaves in coconut milk), pork and chicken, octopus. While the food cooked we conducted some pile sorts. Then we got dressed to dine with matai. Several families from the village had also contributed to the 'umu meal with the chiefs. We had three #2 pigs, including the one we'd watched being prepared, 4-5 chickens, and twice as many fish. There was also the yams, taro, and octopus! It was all delicious and super filling. I particularly enjoyed the octopus. We ate with the chiefs, exchanged greetings and took photos, and then several of them stayed to be interviewed and administered the pile-sort activity. After the pile sort, we received a special gift from the High Chief. He had had his family made a special sweet taro dish that takes over 24 hours to prepare and is a treat (I think it was fa'ausi). We were grateful, though we were extraordinarily full from the 'umu.  Leota conducts pile sort while Josh and Grant take notes. Leota conducts pile sort while Josh and Grant take notes. We went to the High Chief's house in the evening to conduct more pile-sorts among his family. It was Sunday, and I wondered how much Christian piety the Samoans would show toward drinking in Savai'i on Sunday. They'd apparently appreciated the beer we'd brought and drank with them on Friday, and we'd had more with them on Saturday night. The High Chief was drinking a Taula when we arrived, so that answered one question. Then he broke out a bottle of red wine to share with us, which answered the other question. I wasn't really looking to drink while we were collecting data, but I accepted a glass. However, my stomach was full as hell from all the food, and the wine did not sit well with me. They wanted to feed us too, and even though we were full from the 'umu, they brought us grilled tuna sandwiches. I nibbled down half a sandwich. As Josh conducted a pile-sort with one of the High Chief's family, I felt the nausea creep up on me, and I started breathing deeply to prevent losing it. I started sweating, and my eyes glazed over as I tried to get a grip. Grant noticed these signs, so when I popped up and stepped into the darkness for a minute, he knew why. The High Chief asked where I was going, and Grant told him I just need to get a little air. As I stood off behind a car in the dark, I lost the wine, after which my stomach felt better. I stepped back over and continued the interviews without anyone else the wiser. After data collection, we went back to the fale tele and settled down for the night. I can't recall if it was Saturday or Sunday night, but we got a big storm one of those nights. The wind blew so hard that rain came into the fale tele sideways. I was far enough from the edge that I pulled the sheet over my head and kept sleeping. Leota and Kalama got up in the middle of the night and put up tarps to keep the rain out. Leota thought we were cold because of the sheet over our heads and brought us more sheets. Leota got a photo of me looking like a mummy under the sheets, but he never did send it to me. Saturday, July, 15, 2023

We stopped at another site too see the pe'a pe'a birds (white rumped swiftlets) that nest in lava tubes. Pe'a pe'a bird are nocturnal birds that use echolocation to navigate. Again, yes, you have to pay to see these sites, but consider the impact we are all having on the environment through our tourism. The fee is minimal, and I pay for all of us at each site. Here they get a flashlight per person so we can shine it in the eyes of these poor nesting baby birds. This lava tube is cave not much taller than a human that extends relatively straight off into the darkness, but the nests are all relatively close to the entrance Supposedly this tunnel goes all the way to France, according to another story Leota told us. Our next stop was the lava fields in Saleaula that covered an old LMS church but did not cover a nearby virgin's grave. Mount Matavanu is a volcano in Savai'i formed during the eruption that started in 1905 and waxed and waned until 1911. The lava flowed overland at a pace that allowed the district of Gaga'emauga to pack up and move to 'Upolu. By 1906 it had largely ceased flowing overland but had destroyed the village. Lava continued to flow through the tubes until around 1911. Decades later they were able to return and found that the upper story walls of LMS church ruins were still standing and that a mythical virgin's grave had not been covered by the lava. They took these as signs to their land was protected and returned, though they also maintained their new community in 'Upolu. So their family now reside in the two villages on both islands. The church is made of Samoan concrete, which is made from crushed coral. It's super sturdy apparently. Some of this info I read on the signs, some Leota told us, and some the people running the attractions told us.  NUS linguist Leota Sanele administering a pile-sorting interview. NUS linguist Leota Sanele administering a pile-sorting interview. We were running late getting back to the village in time. Another local chief had asked that we attend a cultural event taking place in family that he had invited me to, but we would not be able to drive back in time, since we were only halfway around the island. We stopped to buy a fish on the way back. Samoans have fish in the water in front of them, but when they want it for dinner, it is easier to grab it from a stand at the market than go fishing. When one goes fishing, it is easier to sell the fish at the market than try to save it to eat every night. The same seems to be true of eggs and other perishables. Have I said that hospitality is their ethos in Samoa? It was wonderful. The food was the best we had the whole time we've been in the Islands. Our bodies never thanked us so much for the good quality food. As middleclass Americans, I think being treated with the courtesy accorded people of high status was a little uncomfortable. Leota and his family served us, and only when we had eaten and were completely finished did they eat. We are grateful for this experience and feel so welcome there. The photos below were taken by Tala Eslekielu Lealamanu'a, one of the many lovely members of Leota's family who hosted us. The respect being shown by our host and guide Leota in the center photo is apparent. Again, I am both honored and embarrassed by this, as Leota is a chief in the village. He is one of several chiefs, but he is important here nonetheless. After eating, we conducted pile sorts with several participants, which I will talk more about in a future post. Then, we went for a swim. Leota had been offering to take us swimming since we'd arrived, but we'd been running late on Friday, then we'd needed to get gas for our tank in the morning. So we finally went in the inlet just across the road from the fale.

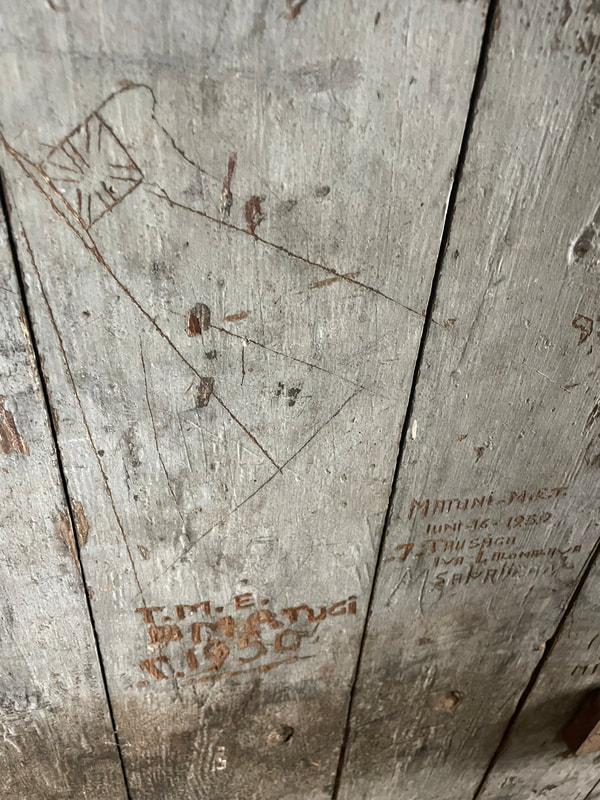

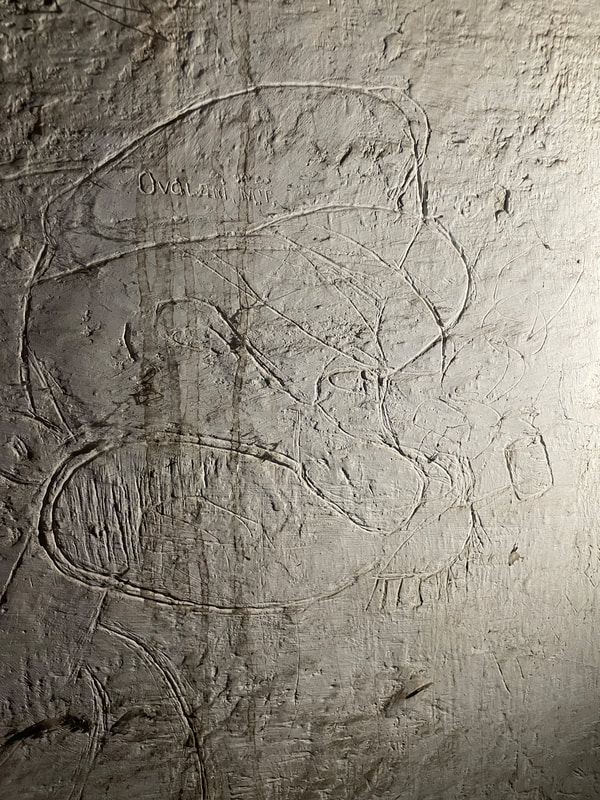

We had been getting to know Leota all day. He told us stories as he drove us around. He preferred to do the driving in Samoa, both because it was easier than for him to tell us how to navigate and also because I think he likes to be in control. I understand that myself, but I am happy to work with people who like to take charge of things. Hanging out in the water gave us an even better opportunity to get to know him. The High Chief had given us special permission to drink beer anywhere we want, including the fale tele and while in the village pools and streams. He'd also given special dispensation for Leota to drink with us. It wasn't something I'd expected though I'd given the money for the beer. Kalama and his son had arrived on the bridge with the beer. We said we were going swimming, and I thought they'd take the beer back to the fale tele. Instead, they walked through the water to a log where we could drink while we were swimming. Apparently, it's a thing. Just like anywhere else in the world--of course it's a thing. Leota and I talked more about our understanding of each other and goals for this visit and our project while drinking beer and floating in the water. Kalama opened them for us and kept the case of warm Taula afloat while the boy looked on. He was relieved by our attitudes and we talked about how we could truly collaborate on things. One of the issues according to Leota, is that Samoans don't really value write their history down. They believe that they live it; why should they record it? The only real Samoan historian they have, he says, is Malama Meleisea. Leota is inspired by Meleisea and wants to record some of the true stories that have remained hidden. But not for palagi, he says, for his own children. When the only stories written in English are the versions told to palagi writers, the children reading those works in school believe them about their own history. So, Leota reasons, it is anti-colonial to be able to resist the complete brainwashing of his children by making sure their legends are also preserved in the colonizer language. It may seem like a weird duality, but I understand it. Hearing Leota, reading what I have about Meleisea, and meeting him personally, I very much want and need to read more of his work, and I'm really excited by the opportunity to work with Leota more closely. Wednesday, July 12, 2023 Example of a pilot pile sort. Example of a pilot pile sort. Last week, when I was first introduced to our translator-liaison Leota Sanele by Centre for Samoan Studies Samoan Language and Culture director Matiu Matavai Tautunu, Leota was told that we would like to go to Savai'i to collect data. Leota laughed and asked if we wanted to sleep like Samoans in the open fales, and we assured him we would. Leota had said to us that this past weekend would be too soon for us to go but that he would be going there to visit his family and would make arrangements. Leota has a home in Lalovaea with his wife, daughter, brother, sister, and cousins, but he is from the village of Gataivai in Savai'i and has a home there with his extended family. However, I did not want Leota to feel like we were foisting ourselves on his family, per se, so much as helping us get by in Samoa. As we were to learn, the ethos of hospitality and service is central to Samoan identity, though that doesn't mean it's not an imposition. Having a bunch of palagi (white people) descend on a family is as much trouble in rural Samoa as it would be in suburban Alabama, so my impulse was to find a hotel or AirBnB to stay in and only come in to conduct interviews if the village chiefs allow it. However, that is not the Samoan way, and I kind of already knew that but was unsure they would want to honor us in the customary way. I panic-booked an AirBnB just in case, and on Monday, Leota told me that the arrangements had been made for us to come for the weekend. This was wonderful, I said, and by the way, I booked an AirBnB because I don't want to be a burden. "The chiefs would like to welcome you with an 'ava ceremony and are prepared for you to stay with us." "I should probably cancel that AirBnB, shouldn't I? Yes, I am canceling that AirBnB." At this point, Leota and I were still getting to know each other, and there were language and cultural barriers. Mind you, Leota has more knowledge of my language and culture than I do of his, but we needed to learn about each other as individuals and our values. An 'ava ceremony is a special ritual reserved for VIPs, so we were being extended a great honor, but such honors entail gifts for the chiefs, the High Chief, the ministers, and the untitled men and women. They would be presenting the same for us. I have partly experienced preparation for one 'ava ceremony before (we prepared but did not ultimately receive the honor), and seen gifting around the sama ceremony after tatau, so I had some idea. Things and time cost, so I would need to reimburse the chiefs and the family in some form and be prepared to do so up front in ceremonial fashion. Leota would give me a budget later in the week, which was really a means of kicking the issue down the road for him. Leota did not know what I know, so he was justifiably concerned that I might fear they were trying to extract resources from palagi. This is the heritage of the colonial encounter after all. Furthermore, I should book our ferry right away, said Leota, since we would be taking our rental car over with us, so we did that on Monday (I forgot to mention that fascinating detail in the previous post), buying tickets to leave at one time on Friday and returning a different time on Monday. The date format is New Zealand style too, which causes me a little confusion sometimes. This is foreshadowing. On Wednesday, we met up with Leota to create our test pile and pilot the pile-sorting activity. After developing a set of bilingual cards with Leota, we walked him through the activity. The free-listing and pile-sorting methods were developed for research in cognitive anthropology. Terms elicited from cultural experts in the free-listing stage are sorted into categories based on how a person thinks about them in their minds. Leota is a linguist interested in Samoan folk knowledge, so this was inherently interesting to him. We found that he and many Samoans we interviewed enjoyed the activity and liked talking about how they organize Samoan concepts in their minds. We eliminated some redundant terms that we had not caught before, corrected our Samoan spellings, and ran another pile sort at Leota's request. One of the issues with the activity is that people may categorize things in their minds differently at different times and when they have different understandings. After the first time around, Leota thought he understood the purpose of the activity better and, reflecting on his initial piles, wanted to do it again. This desire to repeat the activity would take place several times in the field, though in some cases this may have been an innocent effort to earn another subject fee, which were all being donated to a church youth group. That evening, we finalized the card terms for Savai'i. These cards were not considered final at the time because we were still awaiting terms from our colleagues in American Samoa, but we received them by email while in Savai'i. We were able to quick check for any glaring terms that hadn't previously been mentioned and conducted a recount upon return from Savai'i. There were new terms, but their mention rates weren't high enough to be included in the final pile set. Thursday, July 13This was a glorious day (sarcasm) of catching up on other work on the computer that isn't worth taking photos of, such as filling out expense reports and stressing about our funds. We also did a little shopping for supplies and getting multiple sets of our cards made up so we could conduct multiple pile-sort interviews simultaneously. Grant also bought some Koko Samoa paste. Koko Samoa is ground cacao, mixed with something to form a paste. A tablespoon or so is mixed with hot water to make a beverage that is kind of chocolatey but also just a little oily. It's what many Samoans drink instead of coffee or tea as a stimulant, and Leota's family drink it with every meal. I've never made it myself, so Grant was interested in experimenting. I emailed Leota about the budget and finally got a quote of the amount of cash I would need to compensate the families for our accommodations, as Samoa is still a cash economy for the most part, and the only international ATMs are in downtown Apia. Getting large amounts of cash out of the ATM has to be planned for, as I have a UA purchasing card to use for research purchases, but it doesn't allow cash withdraws. So I have to make the maximum daily withdraws from my personal account, family account, and personal credit card to cover expenses, then quickly fill out an expense report to submit for reimbursement before it negatively impacts my family back home. Stupid nonsensical bureaucracy. Friday, July 14 Mommy's Baby couldn't take care of us. (Photo taken March 2023) Mommy's Baby couldn't take care of us. (Photo taken March 2023) Friday was quite an experience. While I was packing up the car, Grant made the Koko Samoa. He didn't know how to make it so he looked it up on the internet. In retrospect, I think either the internet or Grant got the ratios wrong because, well, we'll get to that. Grant offered Josh and I some, but we weren't interested, so Grant drank the whole pot, reasoning to himself that he didn't want to waste it or leave the pot to mold while were were gone. I had told Leota that we had tickets for the 2pm ferry, which meant we needed to be there to board by 1pm because of the maneuvering it takes to squeeze as many cars into the ferry as possible. As a tulafale (talking chief), Leota was the orator on behalf of NUS as well and had a role in the commencement ceremony taking place Friday morning. He suggested we pick him up at noon, so he wouldn't have to leave his car at the ferry parking lot over the weekend. I was concerned that Leota had given us a low budget, so I wanted to go to the ATM again before we picked him up. Unfortunately, I chose a terrible time, as the ATMs are in the center of the business district, which is the most traffic-congested area. We also realized we were low on gas, so we tried to stop and get gas, but first I missed my turn, then found the station on the way to NUS temporarily closed, so we would have to get it on the way to the ferry, which is about an hour's drive from Apia. On the way to NUS, Leota had called to see where we were and suggested we meet him at the ferry because commencement traffic was so bad on campus that he was concerned we would be delayed getting to the ferry. However, I didn't hear my phone and called him when we got on campus to ask him if he could come to us, since we were stuck in a jam, at which point he relayed the suggestion. It cost us about 30 minutes getting onto and then back off of the campus, which meant we would have to drive like a Samoan taxi driver (weaving in and out like a bat out of hell regardless of speed limits or double-yellow lines) and didn't have time to stop at a gas station either. As we're hurtling toward the ferry, Grant suddenly says, "Guys, I'm not feeling well." And I ask with alarm, "Um, what do you mean you're not feeling?" I've just gotten to know Grant over the past few weeks, but he's the kind of person who likes to will himself to be fine and fight through things, not the kind to just casually mention that he's not feeling well. "It's the Koko Samoa. I feel like I might get sick." "Do I need to stop?" This sounds incredibly selfish of me. Of course I should stop. On the other hand, Grant is the type of person who would almost rather die than be the weak link, so he literally might not want us to and have other plans. "No, I'm gonna hold it in. I refuse to be sick." As we approach the airport, which is about 5 or 10 minutes before you get to the ferry, I pull out the ferry tickets to have them ready and look again at the dates and times. And what do you know? I have flip-flopped the departure and return times in my head and not doublechecked myself before making plans. Our tickets were actually for the 12pm departure, and we should have been here by 11am. Our collective stomachs drop.  They'll fit about six more cars in here with us. They'll fit about six more cars in here with us. We pulled up to the lot where cars park to await the ferry, and I told the guys checking tickets my problem. I tried to supplicate myself as a dumb palagi (true) who gets confused by the day-month-year format (also true) and got the days and times reversed in my mind (sigh, true), and the guy said, "OK, that's cool, you can go ahead and get in line for the ferry there." We breathed out, thanked whoever each of us thanks, and pulled the car up. I was shaking from the blood sugar crash that comes after acute stress. Then the same guy comes up to my window and says, "Your ticket is for 12. You were supposed to be here at 11." "Yes, " I said, "I just said that, and you said to pull up here." "Ohhh, you'll have to go on standby," responded the agent. "You'll probably get on today." "Probably? Today?" I supplicated myself. "There are...five cars ahead of you, so maybe the next one even, but probably today. You'll have to pay a ticket change fee though," the agent assured me. "How much is that?" I asked "$40 tala plus surcharge," he said apologetically. That's around $15 USD, so not much for such a dumb mistake on my part in my opinion. According to Samoans we interviewed, part of the Samoan ethos of service is to be agreeable. Agreeableness is a critical mode of interaction between superiors and subordinates in Samoan society, but it is not always immediately clear when meeting strangers who is higher and lower status. Being generally agreeable to strangers is a way of hedging bets and ensuring no social boundaries are violated, especially on a small island where everyone is somehow related. But I think it's also sometimes true when Samoans address foreigners, whose statuses relative to their hierarchical society is harder to discern. I think what at first seemed a bizarre misunderstanding--the indignant voice in my head wondered if this person was not actually listening to me--was a manifestation of this Samoan impulse to be agreeable. Or I may have just talked quickly and nervously in my American accent, and he didn't understand anything I said, waving me forward when he saw my ticket and only noted the time was wrong when he took our names and went to check us in... Leota arrived and found us in the standby lot. I told him what happened and could see the concern on his face. The 'ava ceremony that was planned for us was a big deal, and he worried about upsetting the chiefs by keeping them waiting. At first he suggested that I come ahead with him and leave Josh and Grant to bring the car over (you can get a ferry ticket without a car easily and on-site without reservations). "But what if they don't get on. I can't leave them here." He agreed. Leota decided he would go ahead and tell the chiefs about the delay. If we got on the 2nd ferry, we could still conceivably get to the 'ava ceremony just in time for it to start but without any time ahead of time to settle in. Under the circumstances, I considered that quite a relief. We could adjust to that, but what we wanted to avoid doing is giving the chiefs the impression that we were not honored or that we did not take it seriously enough to make sure we had our arrangements straight. Leota went ahead on the 2pm ferry. Grant wandered off to get air. Josh went to the snack bars to find lunch. I also grabbed a snack--a nourishing bag of chicken Bongos and a refreshing bottle of Coke--and returned to sit in the hot car just in case something happened involving our chances of getting on the 2pm ferry. We had the hour to wait while the ferry was loaded with ticketed passengers and could not even make use of the time to get gas, so we were going to have to get gas on the other side. There were not many gas stations in Savai'i according to Google Maps, and the few were near the ferry, so we gambled they would be open when we eventually got over. When the last scheduled car went aboard, they started slowly bringing standby cars on one by one, slowly maneuvering each into a crevice before bringing the next on. The four cars in the front row went one by one, then the car next to us was put on. Then, they waived us over. "We're going to get on?" "Yes," said the agent. I handed my money and tickets. "What about theirs?" the agent asked me about Josh and Grant. I collected it and stuck my hand out the window, but the agent had stepped away. A guy loading the cars had just given the "cut" signal. My hand was still sticking out the window with money and tickets. "Ohhh, sorry, no more. You'll be first on the next one." So I got my money and ticket back and backed the car back into standby line. We got on the 4pm ferry, as Leota had anticipated. The cars were packed so closely together that doors could not be opened. Grant climbed out the window at one point to find a restroom and explore. I hunkered down for the hour and took a little powernap to prepare for the rest of our evening.  Ferry to Savai'i Ferry to Savai'i When we rolled off on the other side, we were a little bewildered. It was a much smaller lot, and we rolled quickly out of the lot and onto the main street, where we saw Leota driving a van with an older man in the passenger seat. I got out and went to greet them. "This is the High Chief," Leota introduces me. I am startled but greet him graciously. I did not expect to meet the High Chief until the 'ava ceremony, but here he is in the van with Leota drinking a beer. I found it disarming. However, the ride, nap, surprise, relief, whatever had washed the need to get gas from our minds until we passed the gas station. We looked at our gas gauge. It still had two bars. It had had two bars all day. The first tank had lasted a long time, so we agreed that two bars would be fine until we could get back to these gas stations tomorrow. Five minutes later, I hear a "ding" and look down. We had zero bars, and the "empty" light was flashing. Our stomachs were back in our mouths. I called Leota. and babbled in panic about how the bars had been this and that and how far was it to a petrol station? This is not what we call them in the U.S., but the ones we'd pass all say "petrol" on the signs, and the colonial heritage in Samoa tends to be primarily New Zealand (British Empire) and German. By contrast, the colonial heritage in American Samoa is primarily US and some British. "You need gas?" Leota clarifies. I stop babbling. "Yes." "There's no more gas stations to the other side of the island." This is no longer true, but even Leota did not know this, as several have popped up along the road beyond his village in the past few months. "We're almost to the village. You will make it." "Oh, okay," I say. The reality, as Leota and I discussed later, is that we were still struggling to understand each other, as Samoan is his first language and American-English is mine. Samoans from Samoa tend to speak English with New Zealand accents, and Samoans from American Samoa speak English with American accents. This is pretty intuitive, I know. But Leota is a linguist, and words are important to him, and he was wondering if stereotypes about Americans were true. We don't all fit the American stereotypes, but they have been earned by Americans as a culture. Leota was wondering if we would behave like entitled palagi from one of the current hegemon cultures of the world--would we be offensive and offended? During this phone interaction, I was making things tense because he couldn't understand a damn bit of what I said and worried I was having some weird palagi overreaction to needing to get gas when clearly the goal was to get the High Chief straight and directly to the 'ava ceremony. So on we drove. "Almost" was about 45 minutes, but we had to make a stop at a local store as we approached to buy the 'ava, which comes in 1 lb. bags for about $10 Samoan tala or ~$4 USD. I turned off the car to save any fumes we had left and prayed it would start again to finish the trip. It did. We arrived at the village without running out of gas! We are overcoming challenges today by dumb luck. We are shown into the bathrooms to change. One is in a partly enclosed fale with its own toilet stall and shower constructed for a family member who had grown up in an enclosed American-style home in American Samoa but now lives here in Savai'i. The other bathroom stands alone behind a few fale. All the land is owned by families organized in villages, and they build fale for family members to live in where the extended family as represented by the chiefs have agreed it's okay for a family member to live. Each family is expected to work the plantations on the land, and the families all live communally in mostly open fale and share in the work and rewards. I'd had the boys buy new ie faitaga, the tailored style of lavalava with pockets and straps worn for more formal contexts like church and work, and I'd brought mine. However, I hadn't put an ie faitaga on in several years, have only worn it a few times to begin with, and have never put one on in a dark bathroom with an anxious Samoan linguist waiting for us to join the chiefs, who were already gathered in the fale tele. Fale tele are the large fale in the malae or gathering square in front of several houses in all Samoan villages. The presence of these fale tele signify hospitality, welcome, and love, which are the highest values of Samoan beliefs and folklore, according to Leota, who is a Samoan folklorist as well as linguist. We struggled poorly into our ie, but it was good enough. Leota met us before we went in and was anxious. The 'ava ceremony is a special event that does not happen very often and is done for important dignitaries. Many chiefs want to meet the dignitaries, and so there were more chiefs in attendance than Leota had anticipated who we would need to provide gifts of respect for. This was literally the only possible crisis I'd been sage enough to plan for and handed him the cash. He would be in charge of distributing gifts during the oration as our representative. His relief was palpable. We were seated in the fale against one side with me in the middle and Josh and Grant and either side of me. I was the guest of honor. My status there is based on my academic credentials as a full professor from US university, and so I would sit against the center pole. I forgot to tell Josh and Grant to sit against poles, so they were simply to my right and left until they were told later to use the pole during ceremonies. They were being honored as titled guests because they were my assistants, whereas Samoan assistants would be the untitled people outside the fale and carrying items between chiefs and guests. Most of the chiefs sat across and to the left of us. The High Chief and Leota sat along the right side. The untitled men assisting were just inside the entrance to the left side, and the untitled and titled women were outside the fale taking photos on their iPhones (fortunately--thank you, Tala!). We all sat cross-legged on the floor. Leota was our orator, so he spoke for us and translated, though most of the chiefs also spoke varying degrees of English. The orations are formal actions of the 'ava ceremony, and we sat as centerpieces and essentially took it in. A staff of 'ava was brought to each of us as a symbolic gift as Leota told the story of 'ava, which he related to us later in English. 'ava or kava is Piper methysticum, a bush that only grows in the South Pacific. Throughout those Pacific cultures, kava root is ground into powder and strained through water. It gives a mild analgesic effect and pharmacologically is a GABA agonist. It tastes like dirt, so the convention is to drink it down in a single swallow a shell (half coconut) at a time. Kava bars have popped up in cosmopolitan places around the world that gussy up the tastes sometimes while retaining some of the Pacific trappings. I actually like to drink kava at work to help me focus while staying hydrated. In Samoa, 'ava is used ceremonially, but it is also like beer for them. As Leota says, before they had alcohol (I find it surprising that the peoples who settled Polynesia didn't have fermentation technology), they had kava, and one sees men gathered around 'ava bowls at markets like one would see men doing with alcohol in other locations and cultures. After Leota and the chiefs tell the 'ava story and thank us for coming, I give an impromptu speech on behalf of the three of us thanking them that Leota translates for the chiefs. Then they begin bringing us food. In Samoa, the highest status people eat first. In families, children serve the adults and only eat when the adults finish. When chiefs gather, they are served first, and untitled people eat when the titled people have finished. Thus, we were served with the chiefs, while Leota (who is titled but serving us as a gesture of hospitality) and the untitled men and women brought us food. And they started with cocoa Samoa. I heard Grant groan. The food they brought us was magnificent, and there was so much! There was a whole fish, a quarter chicken, coconut soup, a bowl of caper-like seaweed, yam, niu (baby coconut opened for coconut water), and a never-ending cup of Koko Samoa. And warm Taula, the local beer. This was our contribution to the party. As we leaned over our knees to pick up our food, the High Chief took pity on us and instructed the untitled villagers to bring chairs and tables in for us to sit on because palagi aren't used to sitting on the floor for long periods of time. He laughed. He was not wrong. My hips and knees scream after 10-15 minutes in that position. As we ate, the untitled men and women were watching us. No sooner did we put a morsel of food in our mouths than they swooped in and presented the serving dish to offer us more. I love eating and especially love eating new food, but I was quickly full and had been feeling nauseous on much of our trip, so I could not finish the first round and had to beg off offers of more. Grant however reminds me of a younger version of myself and likes to prove himself by doing more and better than people might expect from an average-looking white dude, and he took it on as his personal duty to make us look good as palagi who could hang with the perceived Samoan diet. And if it weren't for the Koko Samoa that Grant poisoned himself with that morning and the warm beer we'd contributed. We were sitting on chairs to the side now, not directly facing the chiefs. Instead, we were sort of facing the High Chief and Leota but more to one side and not in direct view. The High Chief smoked hand-rolled cigarettes and Leota sat there talking with the chiefs and still not eating, since he was acting as our servant. Grant took a drink of beer, which he wasn't a big fan of to begin with because of the way it foams up in one's stomach. And it had foamed up in his stomach and come right back up his throat. And suddenly Grant vomits across the table in front of us and on his own and Josh's ie faitaga. I scooted away just in time as I saw it out of the corner of my eye. Leota noticed something had happened but not what, and I was able to tell him that Grant was sick without attracting any attention. Leota called the untitled women over, who took Grant and Josh to bathrooms to wash up. Josh was back quickly while Grant took longer. We felt terrible for poor Grant and whispered to Leota what had happened with the Koko Samoa that morning. He assured us that the 'ava ceremony was over and the chiefs had not been paying attention to us. When Grant returned, he was embarrassed and upset with himself for not willing himself to not become sick. We assured him that no one seemed to notice, and truly, it seemed that even the untitled men and women did not realize why Grant and Josh had been ushered to the bathroom. Perhaps they thought they'd spilled something or wanted to wash up in the traditional American style, rather than use the bowls of water brought for us to rinse our hands in after eating. We could tell when we later stripped the coverings from the pillows on the chairs and table covering to be washed. They were mystified as to why until we said that someone had been sick. The family left the table and chairs in the fale tele, as that was also where we were to sleep at night. The High Chief had given us permission to sleep there and to do so with wearing lavalava, which are otherwise required in this sacred space. We were set up to sleep uncomfortably close to the table and chairs where Grant had vomited, so I selfishly made Grant take the side nearest the table and slept closer to the middle. Our bedding was the pandanus leaf mats on the concrete floor and two pillows and a sheet apiece. They set up citronella incense spiral burners to keep away the mosquitos, and brought us an extension cord so we could charge our phones.  Our space in the fale tele Our space in the fale tele Several village dogs adopted us. The animals and people have interesting relationships. The animals wander freely and have clear roles, but they're not really treated like pets or farm animals. Dogs run around and protect each family's area from the usual passersby, as well as keeping the pigs from getting into things they shouldn't. But even the puppies don't get named and played with by the kids. They seemed amused that we kept putting our hands out to befriend the dogs. Nevertheless, the dogs protected us in the fale tele. Lucky us. They barked at people passing by on the road throughout the night, and at one point they protected us from what sounded like a roving gang of other dogs based on the chaos of their very loud fighting. Leota was also sleeping with us it turned out and had a cell phone that chirped notifications all night. Grant ended up getting a headache and could not sleep. I slept OK for being on the ground but awakened frequently throughout the night. At one point I noticed that Grant was not laying down and had not been for a while. He'd paced the fale tele for a while, then gotten into the car to sit in a different posture and ease the tension to his head to get rid of his headache. As soon as the sun rose, those of us who had slept awakened. That wouldn't be the case every morning, but it was that first morning. Sitting up, we could see everyone in the nearby community was rising. Twenty feet away on most sides of the fale tele was family fale full of people coming to life--five in this one, twenty in that one, three in another. No walls, no rooms, not much in the way of dividers. No kitchens. We could see our neighbors sitting on the floor looking at their iPhones, while we saw others preparing us breakfast. Starting with Koko Samoa. Actually, we still had Koko leftover from the previous night, and Koko Samoa may be like coffee for Samoans but not for me. I like Koko Samoa and drank it every time it was offered, but I've got a coffee addiction and get a headache if I don't get a certain amount a day. I travel with instant coffee singles just in case, so I'd grabbed a few of them to mix in for Josh and I.

"None?! Oh, i just thought you would need to get gas before we drive around today. You won't make it to the ferry."