|

I’m writing a book proposal for my work on dissociation, and it’s hard not to include every pop culture reference as I come across them. So, for the time being, I’ll place this right here. A great nod to Gordon Gallup’s hypothesis that mirror self-recognition is indicative of self-awareness, from Big Mouth. My students turned me on to this show, so I’m watching it with my teenage son. He, of course, has already watched both seasons twice, but it’s a nice opportunity to bond and is funny as shit.

0 Comments

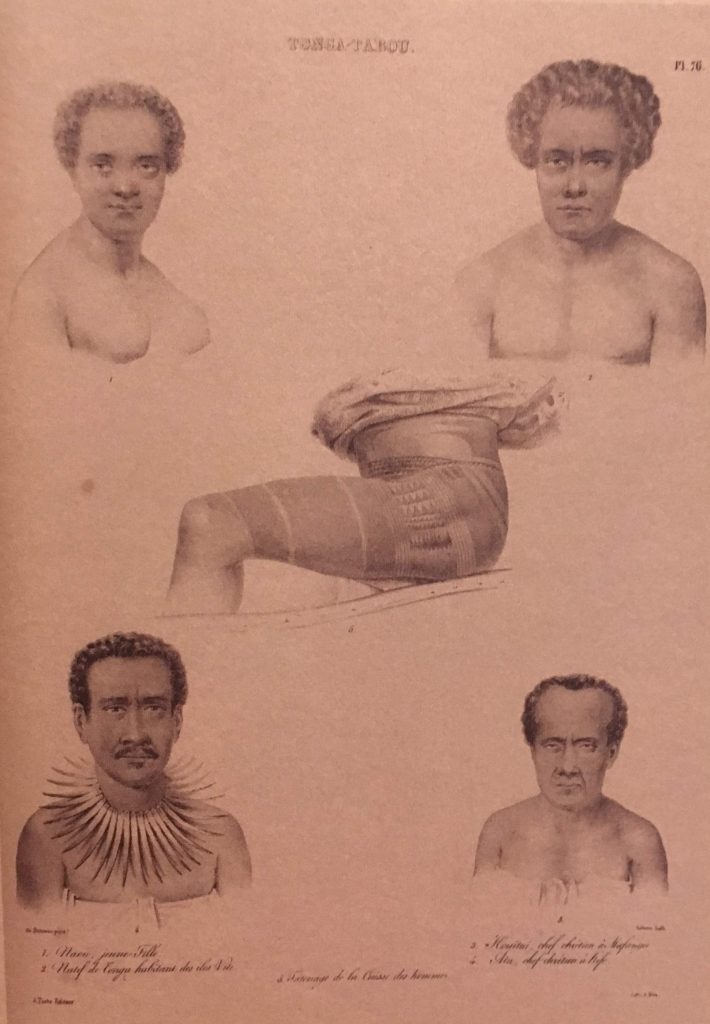

Oh, they tried. According to Mallon and Galliot, the decentralization of Sāmoan authority may have played a large role and been abetted by the later arrival of the missionaries in the Sāmoan archipelago than to other islands. The initial missionization of Sāmoa was conducted by John Williams and the London Missionary Society, which had gone first to Tonga. Tonga and the Sāmoan Islands are close and have a long (and tense) history of close interaction (this according to a book I picked up published by the Samoan Studies Institute of the American Samoa Community College that I will have to track back down to cite appropriately). Thus, there have always been lots of Sāmoans in Tonga and lots of Tongans in Sāmoa (with the requisite slanders against each other--see my previous post for a bit on this in my field experience). In Tonga, they met a Sāmoan who had already converted to Christianity (not sure how, but there were vagabonds, outlaws, and castaway Europeans who had arrived in the Sāmoas earlier and set up heretical little Christian cults for themselves before) and who became their emissary and assistant in Sāmoan Christianization (this is my memory from reading Robert Shaffer’s coffee table history, American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag) while sitting in Off Da Rock Tattoos waiting for Joe to finish tattooing so I could collect another saliva sample).  Drawing of Tongan tatatau by Louis Auguste de Sainson, official draughtsman of the voyage of Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumon d'Urville 1826-1829 on the corvette Astrolabe (From Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 31)[/caption] Drawing of Tongan tatatau by Louis Auguste de Sainson, official draughtsman of the voyage of Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumon d'Urville 1826-1829 on the corvette Astrolabe (From Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 31)[/caption]

Importantly, early European reports of South Pacific tatau have it that Sāmoan and Tonga styles were similar or the same and characterized mostly by description of the pe’a, the male tatau the looks like nearly solid blue shorts. But Tonga was centralized under King George Taufa’aahau, who was Christianized by 1831 and banned tattooing in 1839 in the Vava’u Code, Tonga’s first set of laws. This effectively ended “traditional” tattooing as practiced by Tongans, but this did not apparently stop the Tongans from getting tatau—they simply traveled to Sāmoa for them! The same was true in other Pacific Islands. Makiko Kuwuhara indicates that tatau had disappeared in Tahiti shortly after the arrival of missionaries in the early 1800s in Tattoo: An Anthropology, and Tricia Allen notes the same pattern for Hawai’i in Tattoo Traditions of Hawaii. According to Mallon and Galliot:

Part of the issue was that not enough missionaries were in the Sāmoas to have the kind of impact they’d had on other islands without the help of a central native authority. A previous Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS) mission had made a small number of converts, but the mission was ended early because John Williams of the London Missionary Society (LMS) convinced the Wesleyan London HQ that the two missions (WMMS and LMS) had agreed to give LMS free reign over the Sāmoas. WMMS didn’t return until around 1857 and seems to have been somewhat indifferent to tatau. Reports about missionary indifference to tatau are ambivalent though—the issue seems to be that missionaries were aware of their limited numbers, precarious support, and potential for backlash if they were too heavy-handed in banning everything Sāmoans liked about their own culture. Tufuga tā tatau (tattoo master craftsmen) were considered matai (chiefs) and garnered high rank, status, prestige, and honor. Tatau ceremonies were huge village expenses lasting weeks to months that bonded alliances together. For instance, German colonial efforts to limit the authority of matai is what led in part to Sāmoan colonial resistance and forging allegiances with the U.S. and British to push the Germans out.  Auta collected before 1871 and now in the British Museum collection (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 43). Auta collected before 1871 and now in the British Museum collection (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 43).

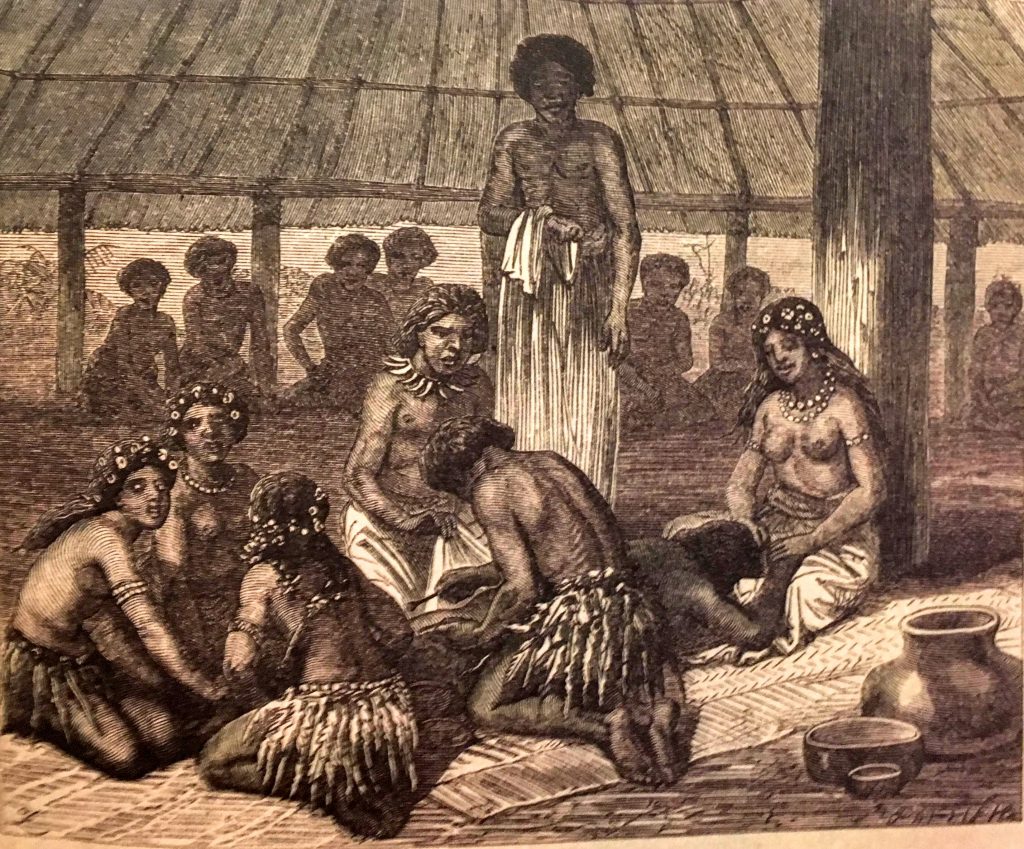

Sāmoan culture may have also benefited in ways from a period in which several matai were struggling to attain dominance over others but not succeeding. Part of Williams’ LMS missionization strategy in the Sāmoas was to convert chiefs who would impose Christianity in their territories. Not long after he arrived in 1830, he converted powerful chiefs Mālietoa Vaiinupō and Tui Ā’ana Tamalelagi, who made it possible to establish long-term missions in several districts. However, other districts resisted specifically because of traditional oppositions to the ‘āiga sā Mālietoa (Mālietoa clan). Williams realized he couldn’t institute laws without backlash by the powerful opponents and thus trained his missionaries to apply a light hand, making themselves available to give advice and so practice a more subtle form of evangelizing. Thus, Sāmoans were able to pick and choose what aspects of Christianity they wanted to abide by and which they did not. The ability of some matai and their villages to hold out—and, ironically, an extended period of civil war among Sāmoans in the 18th century—may have protected much of Sāmoa’s cultural traditions, including tatau, from being relegated to the wastebin of the Christian missionization. Many districts on the big islands of Upolu and Savai’i remained untouched by LMS even 30 years after Williams’ arrival. Not far from where John Williams first landed in Savai’i, for instance, Chief Su’a of Salelāvalu remained faithful to native beliefs and maintained the last temple shrine in Sāmoa, a temple of Taimā (Taemā and Tilafigā are the twin women fabled to have brought tatau tools to Sāmoa and gifted them to ‘āiga sā Su’a).  Tattooing day in Samoa 1868-70. Illustration for a publication titled 'The Natural History of Man: Being an Account of the Manners and Customs of the Uncivilized Races of Men' (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 49) Tattooing day in Samoa 1868-70. Illustration for a publication titled 'The Natural History of Man: Being an Account of the Manners and Customs of the Uncivilized Races of Men' (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 49)

Despite how über-Christian Sāmoans are today, their adoption of Christianity was reportedly very strategic. Missionaries arrived with cool swag (metal stuff, linen cloth by all accounts was just way more comfortable on the loins than siapo bark cloth—go figure), and chiefs could obtain prestige in their communities by allying with them. But the missionary period coincides with a struggle for the four pāpā—the four supreme titles of the Sāmoan hierarchy that comprised several large alliances—to become Tafa’ifa or sovereign over Sāmoa. The previous tyrannical Tata’ifa has literally just been offed by villagers from Fasito’outa weeks before Williams arrived. Thus Williams was faced with converting chiefs who were in the process of consolidating power for their own purposes. Thus, they would promise to obey Christian rules not to kill thy neighbor…right after they killed all those SOBs in the districts that opposed them. Ultimately, Sāmoans chiefs allied with various missions and colonial powers in attempts to attain hegemony in the archipelago, but no one power ever actually succeeded. Since there is little record or description of Sāmoan tattooing before the colonial and missionary period, it is unclear how much tattooing changed. It appears to have varied throughout the islands, consistent with the prehistory of political instability across not just the Sāmoan Islands but also in conjunction with the extended relationship with Tonga. An ethnographic account by German naturalist Augustin Krämer (probably largely co-authored by Sāmoan chief Tofā Sauni), who worked in Sāmoa from 1897-99, suggests that the missionary impact on tattooing was that it transformed from being a large public ceremony to being a private one. The political system of Sāmoas remained largely intact; thus, tattooing was preserved in Sāmoa. Some of the larger changes in how Christianity appears so ubiquitous today in Sāmoa would come later with the arrival of the Mormons, Seventh-Day Adventists, and Pentecostals; but, while some of these continued to ban tattooing, some of the staunchest defenders of tatau today are among Sāmoan Christian pastors. More on that in a future post as I continue to explore this amazing book! |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed