|

I am excited by the prospects of returning to the field next summer to do more research, as I’ve been digging into relevant theory in cultural evolution that is, I believe, spot-on in outlining what is going on with the resurgence of Pacific tattoo cultures. I’m struck by how completely so-called traditional tattooing practices were quickly purged from many Pacific cultures in the 19th century. (I use the term “traditional” as shorthand, since Pacific cultures have maintained tattooing practices to varying degrees during this period and never been isolated from the influences of each other or outsiders—according to Samoan poet and activist Albert Wendt, as quoted by anthropologist and Te Papa Museum Senior Curator of Pacific Cultures Sean Mallon in “Against Tradition”—there is no such thing as “traditional.”) Mind you, we all know what shits missionaries and colonial agents were in trashing native cultures, but it wasn’t one-size-fits-all trashing. For instance, the French were more interested in trade alliances than enforcing decorum, such that it appears many French colonials got tatted up in native styles to show their sincerity (e.g., Bienville). It’s like when our ALLELE guest speakers throw out a gratuitous “Roll Tide” at the beginning of their talks to ingratiate themselves with the audience, except, well, way more committed to their cause (I wonder if LSU ichthyologist Prosanta Chakrabarty will say “Roll Tide” this week when he gives his talk two days before Bama whips LSU’s patootie…). https://twitter.com/PREAUX_FISH/status/1055465915033247744 I’m a few chapters into reading Makiko Kuwuhara’s 2005 ethnography on tattooing in Tahiti (efficiently titled Tattoo: An Anthropology), and she notes that Tahitian tattooing almost completely disappeared right out of the missionary gate in the early 19th century (perhaps why we don’t see any tats in any of those Gaugin paintings). Tahitian tattooing reappeared like it did in the mainland U.S., among fringe and “deviant” types and in similar motifs. Then, what is so fascinating to me, traditional tattooing was reintroduced by Samoan tufuga ta tatau (tattoo masters). I am imagining the Samoan tufuga who reintroduced traditional tattooing to Tahiti was the Sa Su’a Sulu’ape guild, but I haven’t read far enough in to confirm. However, based on our ethnographic interviews with tatau historian Christian Ausage in 2017, the Sulu’ape branch of the Sa Su’a guild was all that remained and that persisted of traditional Samoan tattooing. Sulu’apes have, as far as we can tell, ensured that the Samoan tradition remained unbroken and taught all active Samoan tufuga today. At least this is one of the things we’ll be investigating. Some of these answers are no doubt in the new book by Sean Mallon and Sébastien Galliot, but I have yet to get my hands on a copy.  Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author). Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author).

I am imagining that a variety of environmental/social factors are at play here, which, in theory, we can mathematically demonstrate with the data in hand. Joe Henrich, Bob Boyd, Pete Richerson, Christopher von Lueden, Alex Mesoudi, Maciej Chudek, and others I’ve been reading over the past few weeks make the case and provide the models we can use to test a few predictions in this regard. Robert Shaffer’s giant coffee table book American Sāmoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag indicates that tattooing and other native practices were banned by missionaries in Samoa but that Samoans just tended to compartmentalize and ignore some of those dictates, while becoming über Christian. Some have derisively called Shaffer’s history a biased account of governmental propaganda, but he was good friends with several Samoans I’ve come to respect immensely, such as Reggie Meredith and Wilson Fitiao, so I don't dismiss it out of hand. The book essentially indicates that, in the mid-19th century, American Samoa asked to become a territory of the U.S. so German mercantile companies did not take them over as was happening with Western Samoa. According to the book, Germans came into Western, set up trade, took land from native peoples, made tons of money, were pricks, and that led to the infamous standoff between British, U.S., and German navy ships that was interrupted by a hurricane (the summary of most brief histories of American Samoa). The colonial powers then simply divided the Samoas up instead of fighting over them, with Western Samoa going to Germany, Eastern going to the U.S., and the U.S. giving Britain Guam. After WWI, New Zealand was gifted Western, which became independent in the 1950s. After that, a quote from former American Samoa Historic Preservation director John Enright from his noir detective series (Fire Knife Dancing, in this case) based in American Samoa seems aptly to describe the circumstances, though it also brings into question the whole please-help-us-U.S. of Shaffer:

But I digress. The simplifying model I’m imagining (great quote from someone via Katie Hinde during her recent visit by the way—“all models are simple; some are useful”) is that:

Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption] Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption]

Among the sources I know I’ll be returning to again and again as I explore this, Joseph Henrich “Cultural Transmission and the Diffusion of Innovations: Adoption Dynamics Indicate That Biased Cultural Transmission Is the Predominate Force in Behavioral Change.” I think everything we need to know right now is right there in that title. [Nerd drops mic]

0 Comments

One of the reviewers for my recent article on tattoos among undergraduate athletes turned me on to another tattoo researcher who I'd previously overlooked. Andrew Timming is an associate professor of human resource management at the University of Western Australia whose focus is the social psychology of work. Of interest to us in particular is his research on perceptions of tattooing in the workplace. How do employers/potential employers view them? How do customers view tattooed folks in businesses they patronize? I like his work because the perception of tattooing research has largely been so coarse-grained. We've been focusing on how people perceive others with tattoos---usually as open-minded people who take a lot of risks---but we all know that a lot goes into that perception and which we struggle to measure in our studies: style of tattoos, quantity, location, quality, how it fits the person, context, other stuff about the person, etc. and so on. Timming's work is digging into specific situations with ingenious nuance. Since he's interested in human resource psychology, his focus gets at a locus where a lot of these opinions and the possibility that we act on them matter. And one of his major findings is something I've been interested in my work. In "Body art as branded labour," he

His intuitively logical finding is that some employers market in hipsterism and edginess and value visible tattoos. Their employees looking cool makes them look cool. I say this seems intuitive, but maybe that's because I worked in the music industry for several years. Working in records stores and music distribution, it was people who dressed in suits or conservatively who had a more difficult time. Of course, it's not all about having tattoos or not having tattoos. What makes tattoos so important is that they are unique as a permanent commitment to style or attitude. Jack Black's attitude comes across quite clear in the movie Hi-Fidelity, but maybe it takes asking for "I Just Called to Say I Love You" to learn that (probably not, but you get my point). https://youtu.be/-ECyX8A3iP0 (Incidentally, I have acted just like this in my former life as a record store clerk. It was because I didn't like the store owner and didn't want people shopping there, but the owner saw me and didn't care. It's really a thing.) I wanted to introduce Timming's work because a new article is out that is getting a fair amount of press. Though it's sort of meta. When I search "tattoo study" on Twitter (yes, to RT my own press □), I get: https://twitter.com/guntrust/status/1053107010898681856 Which leads back to a study that was just published in August in Human Relations called "Are tattoos associated with employment and wage discrimination? Analyzing the relationships between body art and labor market outcomes" by Michael French (lead author) and Karoline Mortensen at University of Miami. They collected survey data from 1323 females (women? men? trans?) and 685 (males) via MTurk and found that

This does not suggest that tattoos are accepted in all walks of life now, but it does suggest what it means to say that tattoos have gone mainstream. The number of occupations where tattooing is now OK has crossed the cultural Rubicon (it's now cool to be a tattooed college professor---elbow patches are only cool if you're ironic or not ironic that you're 'cute'). OK, now this part gets a bit confusing. Another new article out in 2018, this time in Journal of Social Psychology, is "What do you think about ink? An examination of implicit and explicit attitudes toward tattooed individuals" by Colin Zestcott and colleagues. (This is not to be confused with "What do you think of my ink? Assessing the effects of body art on employment chances" by Timming and colleagues the year before.) Zestcott is as assistant professor of social psychology at SUNY Geneseo (note, while neither Andrew Timming, Michael French, nor Karoline Mortenson appear to be tattooed hipster doofuses like me, Zestcott is fully ironic with shirt, tie, and tattoo-sleeved forearm! □). This is a survey study using MTurk as well (40 females, 36 males---again, I self-righteously ask---it's 2018, can we use self-identified gender and not sex, if it's nuance we're looking for, as well as more accurate representation). Zestcott previously conducted a similar study of tattooed individuals with neck tattoos and found evidence for an implicit bias against people with neck tattoos even if they said they were acceptable, suggesting there are still latent negative feelings in the general public against tattoos. While tattoos may be mainstream in general, some tattoos are still not so common or accepted, including neck tattoos. But in this new study, they had folks rate 27 different tattooed people across a variety of dimensions, some of whom had neck tattoos, and took 6 that received the most average ratings to be compared compared to a variant of the Implicit Association Test. While participants expressed negative explicit and implicit biases toward tattooed individuals, those biases were not associated with strong negative emotions or disgust. This is an important point because

Cool, so I don't disgust you... □ All summer after our fieldwork for the Inking of Immunity project at the Northwest Tatau Festival (see video about our project here and follow along on Facebook here), I was asked the same two questions: did you get any tattoos at the convention? And, why are you tattooing yourself? This post is the FAQ to answer those questions, because people seem to find the answers (and the sausage that goes into the science) interesting. Did I get any tattoos at the Northwest Tatau Festival, where around 100 tattooists were working, including some of the most celebrated Polynesian and traditional tattoo artists in the world? Um, no, dammit. I wish. No, I didn’t get any tattoos at the convention because that would have meant I was spending the money folks gave me for research on personal tattoos (and one specifically said, don’t get any tattoos with this). I hoped to maybe get some work done before the convention started, but we were literally working (observing, networking, training) the whole time. The convention was two days, but the malu and pe’a Sometimes this is followed up with this question: You know all those tattoo artists and are doing this research—you don’t get any freebies? Nope, no freebies. First, we were working a convention, where many people had appointments already set up. Second, if they were tattooing me for free, they’d be passing up on paying clients. Three, if I were getting tattooed, I wouldn’t be collecting data—there was literally no time to get a tattoo while collecting data. Believe me, I would love some Poli tat work, and I would have spent donor money on it in a hot second if that’s what it Why are you tattooing yourself? My answer to this question is longer. After the last year of watching and learning about hand tapping and thinking through some of the issues underlying our study, I’ve become intrigued with the mechanics of tattooing, not just the biological mechanisms of the immune response (Do different techniques affect immune response different? Does how much it hurts matter? Do different inks matter? A friend of mine noted the issue with carriers and immune response). While conducting the crowdsourcing campaign on Instagram, I went down a stick-and-poke or handpoke tattoo hole as well. Handpoke tattoos are fashionable at present. Many of you learn about handpoke and recognize them for their previous slang derogation—jailhouse tattoos. And, indeed, if you search handpoke tattoos or stick-and-poke tattoos on Google or Instagram or Pinterest, the aesthetic among many of the twentysomething EuroAmerican hipsters out there doing it is, get drunk with your friends, draw designs, tattoo them on each other. They tend to be small, ironic, and potentially embarrassing. However, they’re also quite popular and prominent in music culture, from Ninja of Die Antwoord to Post Malone. But when I went down the Instagram hole, I found some really amazing handpoke stuff too. It simply looks different than work done with multi-needle tattoo machines. I became interested in what could be done, the inks that were being used, how deep people were going, how it felt, and if I could understand traditional hand tapping better by tattooing myself. In other words, a little participant observation meets autoethnography. And, to me, the And of course with YouTube, we can figure out how to do almost anything nowadays (there’s a great series called AfterPrisonShow on how to make jailhouse tattoo guns and how to teach yourself to use them to become good). https://youtu.be/3qn9FcZZe7E I picked a design I like and thought I could pull off and a part of my body I didn’t care if I screwed up on. I tend to be ambitious, even when doing things for the first time and know I have a decent hand for art, so I chose an ouroboros design. I’ve always loved the symbolism of the ouroboros and feel like life—and particularly our consciousness (see the book I’m writing for more on this)—is a tension between devouring ourselves and thriving. It’s death and birth literally, it’s the cycle of the day, cycle of the year, winter vs. spring, you name it.  I chose to try to make this ouroboros design for my very first self-handpoke tattoo. I chose to try to make this ouroboros design for my very first self-handpoke tattoo.

For the first one, I started with a sewing needle taped to a pencil with a bit of thread wrapped around the end as an ink reservoir and non-toxic, water-soluble blotter ink. The ink was very thick, almost like toothpaste. I shaved the spot on my ankle, then cleaned it with alcohol on cotton balls. (Those cotton balls end up getting stringy and make a mess. The pads used to remove makeup are much better, but I discovered that later.) I bought a light blue thin tip sharpie to draw the design on, but it didn’t work. I had to revert to a regular ink pen. The trick I eventually learned is that as soon as I start wiping away extra tattoo ink to see better, I wipe away the drawing. Therefore, it’s best to get enough pokes to make an outline before wiping it all down and losing the drawing. It can be redrawn, but if you’re using a stencil and not drawing by hand or aren’t steady and accurate with your drawing, you might be in trouble—again, stuff I would figure out along the way.) Before wrapping the thread around the needle, I sanitized the needle with the flame from a lighter, then cleaned it with alcohol.  My first handpoke kit. Note: There's a reason tattoo artists use those little plastic caps to put ink in and stick them in petroleum jelly. This lid is way too big to use to dip, and it moves around too much without something to stick it in place. My first handpoke kit. Note: There's a reason tattoo artists use those little plastic caps to put ink in and stick them in petroleum jelly. This lid is way too big to use to dip, and it moves around too much without something to stick it in place.

That first night, I could not get much of the pasty ink to go in. It was too thick and didn’t flow well, so I accomplished an outline of my design, but it was a raw red outline of punctures. The punctures were not deep and not exactly bleeding, as I was tattooing my inner ankle, and only going about 1-2 millimeters deep, but that spot is apparently very sensitive, and it hurt so bad after an hour or so that I had to stop for the night. This problem led me to wonder what carriers are and why people had mentioned that. So I investigated, and it turns out there is pigment, which varies in density and brilliance, and there are carriers, which hold the pigment and interact with your skin. For instance, alcohol is a good carrier because it moves into skin. And it’s antibacterial. If you watch tattoo artists set up, many will squirt a little alcohol or alcohol-based soap into their ink to get the viscosity they want. So then next night, I played with that, which worked much better. I also tried working with two needles. Most tattooing is done either with machines using various needle configurations to cover more skin faster or various head lengths when hand tapping. I put two sewing needles close together to see if I could speed up this process and make heavier outlines. However, the sewing needles aren’t thin enough to do this well, and I toggled back to the single needle after a time. Also, I don’t think my blotter ink had much pigment, because I had to keep going back over and over the same areas to get enough ink in for the design to show. I did this again until it hurt so bad I couldn’t stand it anymore.  I tried a couple different configurations with the sewing needles, playing with different diameter needles and doubling needles. I tried a couple different configurations with the sewing needles, playing with different diameter needles and doubling needles.

Many hand tappers simply use tattoo needles and tattoo ink, since they are so cheap and readily available on the internet. So I decided to wait till it healed up and go over it again with tattoo ink. And, indeed, I found a bottle of black and a box of 20 sanitized individual needles for $6 each ppd on eBay.  First handpoke effort, using sewing needles and blotter ink.[/caption] First handpoke effort, using sewing needles and blotter ink.[/caption]

Now, in the meantime, all the data collection I’ve already written about happened. Let me recap some of what I've written about over on our crowdfunding site, at least the part relevant here. After the 2nd day in Seattle/Tacoma, I believe, of watching Su’a Petelo Sulu’ape (affectionately known by the tatau community as “The Old Man”) administer malu, Mua of Paka Polynesian Tattoo, the shop hosting Su’a Petelo and his son Su’a Paul Sulu’ape, told me to go out and chat with the Old Man. “He’s been drinking so he’s in storytelling mood. Go have a drink with him.” (Also, as later would become apparent, the Old Man is a high-ranking matai, or chief, and, really, probably equivalent if not literally the Paramount or high Chief of the tatau community, so everyone is expected without needing to be told to go pay their respects to him—this was a way of telling me to pay my respects). It was just me and the Old Man outside the shop, and I asked him about the tool innovations Su’a Peter (another of his tufuga or master artisan sons) had told me about the previous year. The Old Man reiterated the stories of those innovations in great detail. Then I asked him about his inks, since I know Intenz has branded an ink in his honor called Suluape Black. He said the Intenz guys marketed that ink with his blessing based on his ink formula, which he developed personally. He told me about the formula he and his brothers were using to make ink and the secret change he personally had made to get a darker black. I commiserated that I’d played with blotter ink and alcohol to try to understand the issues he’d been facing and showed him my ankle tattoo. This is what got me thinking more about the importance of pigment and what specifically is used as the carrier and how some carriers may dilute or dull pigments more than others or cause them to seep out into the surrounding skin (for instance, I’ve noticed that using alcohol to wipe mine down seems to facilitate the ink to spread out over a broader area, so that there appears to be a grey shadow around my tattoos where the ink has bled beyond the boundaries of the tattoos themselves).  Stick-n-poke kit #1 (left) and kit #2 (right). Stick-n-poke kit #1 (left) and kit #2 (right).

After fieldwork, I went back to experimenting on myself. Long story short, the tattoo needles and tattoo ink work way better. The ink is darker and more fluid, so I can tattoo faster and darker with it. The tattoo needles are also much thinner and sharper, so it hurts less and penetrates better. I completely redid the ouroboros tattoo, then, because the needles was so much finer, it enabled me to have the precision to add some detail work that required a fine hand. The most difficult part was building up thick outlines  Re-done ouroboros tattoo with a bit of my revised kit above. I sketch with the yellow sharpie, then go over it with the green to get the lines right and ensure I can see them. Re-done ouroboros tattoo with a bit of my revised kit above. I sketch with the yellow sharpie, then go over it with the green to get the lines right and ensure I can see them.

For years I’ve wanted a rooster and a fish on my knees. My rule of thumb (which I’m violating literally left and right [both my legs, get it?] lately). When my wife and I were trying to have our kids, I was in a painting phase where I was using acrylics and painting designs on our furniture (e.g., filing cabinets). I painted several with magical symbols of fertility I found in a coffee table book of cross-cultural magical icons. I painted three roosters and three fish, and we ended up with three babies. (Maybe I painted them during the pregnancy, knowing I had three on the way—I don’t recall. My point is that these were important to me and have remained so.) Therefore, my next tattoos were a rooster on the inside of my left knee (it’s easier to reach the inside when one is tattooing oneself, and it’s less subject to distortion when flexing) and a fish on the inside of my right. Most handpoke tattoos tend to be small, but as I noted previously, I tend to be ambitious and enjoy the detail work, so they both ended up larger than first intended. However, I like them, so why not?

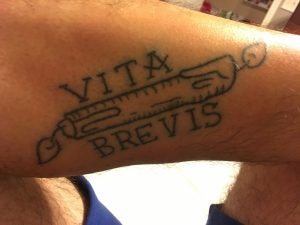

The last one I’ve done to date is something I picked from handpoke flash on the internet. I used to hate flash as unoriginal, but through my research I came to appreciate the Americana style like old Sailor Jerry stuff, and of course Sailor Jerry has become one of the markers of the rock’n’roll, punk, rockabilly, greaser, gearhead, Rat Fink, tattoo subculture I’ve identified with throughout much of my life. So the last one I share with you is “vita brevis,” which I placed on my inner left calf. Vita brevis means “life is short,” and it’s a candle burning at both ends. The full quote, attributed to Hippocrates, is “ars long, vita brevis” or “art is long, life is short,” and perhaps I’ll do an art is long tat on the other calf, but school has started back up and I’m back in Alabama with a thousand other projects calling to me and saliva samples from the field season to get analyzed, so who knows when that will happen.  (Art is long, but) life is short. (Art is long, but) life is short.

One funny thing that won’t happen is that several of my students have seen my tats (handpoke is popular, I’m telling you, so many have them) and not only asked me to tattoo them but offered to pay me to do it. Not. Gonna. Happen.  UA Anthropology graduate student Mackenzie Manns (Photo courtesy M. Manns).[/caption] UA Anthropology graduate student Mackenzie Manns (Photo courtesy M. Manns).[/caption]

Do my tattoos make me look more fit, or fit at all? Gosh, I hope so. Look over here at my guns—er, arms---and not at the middle age gut I’m fighting to suck in. In a study of 6528 undergraduates we conducted nationwide, we found that tattooing may be used by those who are generally more fit, especially among men, to highlight that fact. There is extensive ethnographic literature suggesting that tattoos are signs of status and social roles. They indicate marital status, age, success in life, affiliation, and so on. But contemporary tattooing seems so dispersed and idiosyncratic—do those same motivations still apply in today’s world? In 2012, Rachael Carmen, Mandy Guitar, and Haley Dillon suggested tattoos (and piercing, but we’ll come back to that) fit two evolutionary patterns of behavior—these body modifications may indicate our affiliations with successful groups or injure our bodies so we can heal and show off our healthy immune systems. In 2016, Cassie Medeiros and I wondered if media portrayals of tattooed athletes amplified that signal out of proportion—in other words, are there really so many tattooed athletes or do they just get the most press: ...Or both, in a positive feedback cycle? ...Or are fans more likely to get sports tattoos? After all, athletes at the intercollegiate or professional level are already obviously highly fit people, for the most part, and being recognized for such through through athletic performances---especially if they win! Maybe it’s the folks who aren’t on the teams getting all the ESPN attention who need to shout, "Hey look at MY hot bod!" Or, "Yes, I AM the 12th (hu)man responsible for the decade of football success at the Alabama, as you can see from my 'Roll Tide' tattoo." We tested these hypotheses in two online studies, asking undergraduates if they were tattooed, pierced, athletes, had any college or pro sport-related tattoos, and had ever had any related medical complications. The first study was a national study of 524 respondents but was inconclusive because of the low number of intercollegiate athletes who responded. For the second study, we surveyed all 31,000+ University of Alabama undergraduates and received 6004 usable responses, including 50% of UA’s 572 student athletes and 31 of our national championship (ahem, repeated championship) football team. Here's what we found:

I tweeted yesterday to David Samson that Asher Rosinger is making me look bad, so all the collaborations that make him so productive. Of course, I'm not really competing with Asher. We just profiled Asher's productivity on a recent Sausage of Science podcast for the Human Biology Association, but it is motivating. https://twitter.com/Chris_Ly/status/1048337483220627456 David and I spoke in 2016 about collaborating on a study of sleep and fire. Truth is, both of these guys have been very productive, and David has already taken the first step in this research direction already. In a paper that came out last year (Hadza sleep biology: evidence for flexible sleep-wake patterns in hunter-gatherers. American Journal of Physical Anthropology), David and his colleagues examined sleep patterns among the Hadza with regard to fire and other factors. They did not find an influence of campfires on sleep patterns, but they make a thoughtful suggestion for our future research. How does fire influence waking cognition? We know smartphones, televisions, and the associated blue light has influences on attention and such. It's time to delve into the light that influenced our brains for most of the last 400,000 years. ![A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]](http://evostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/samson-et-al.jpg) A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com][/caption] A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com][/caption]

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed