|

I was heartened this week by conversations with visiting ALLELE lecturer Nina Jablonski, one of the world's foremost experts on skin biology and evolution. I was glad to see that she discussed tattooing in her 2006 book Skin: A Natural History, though she did not go deep on the biology of tattooing. One reason is that there is not much out there about the biology of tattooing that is not essentially alarmist and negative. What heartened me is that she said she gets a lot of queries about tattooing that are beyond her expertise and interest and that she will start referring the (non-quack) queries to me. Which made me realize I'm something of a expert, having conducted one study on the biology of tattooing, read a lot about it, and currently conducting another in the South Pacific with my main collaborator Michaela Howells.  Interviewing Nina Jablonski for "Sausage of Science" and "Science of Race" podcasts with Jim Bindon, Erik Peterson, & Jo Weaver (taking the picture). Interviewing Nina Jablonski for "Sausage of Science" and "Science of Race" podcasts with Jim Bindon, Erik Peterson, & Jo Weaver (taking the picture).

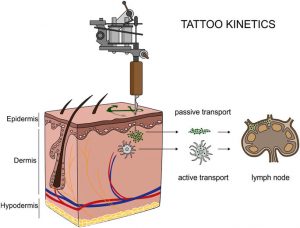

That recognition obliges me to speak up about the study just out in Scientific Reports (a Nature journal) that I have been sent press links about in the last several days. I heard one of the researchers speak about the study on a podcast I listen to regularly (I think BBC World Serivce but can't relocate at moment) and was not impressed. The gist of the study is that tattooing has become extremely popular, but the inks are understudied as toxicants. I beg to differ. The potential dangers of tattoo inks is in fact among the most reported on and studied aspects of tattooing addressed in the biomedical literature, alongside the correlations between tattooing and risk behavior (which is a cultural phenomenon, with little to do with the biology of tattooing aside from the signaling function it serves). < href="http://evostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1-2.jpg"> Translocation of tattoo particles from skin to lymph nodes. Upon injection of tattoo inks, particles can be either passively transported via blood and lymph fluids or phagocytized by immune cells and subsequently deposited in regional lymph nodes. After healing, particles are present in the dermis and in the sinusoids of the draining lymph nodes. The picture was drawn by the authors (i.e., C.S.).1SCIentIFIC REPORTS | 7: 11395 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11721-z[/caption] Translocation of tattoo particles from skin to lymph nodes. Upon injection of tattoo inks, particles can be either passively transported via blood and lymph fluids or phagocytized by immune cells and subsequently deposited in regional lymph nodes. After healing, particles are present in the dermis and in the sinusoids of the draining lymph nodes. The picture was drawn by the authors (i.e., C.S.).1SCIentIFIC REPORTS | 7: 11395 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11721-z[/caption]

The fetishism of tattooing in Euroamerican culture over the past few decades is reflected in the alarmist focus of the dermatological literature. Mind you, I don't dispute the findings of the researchers this this Scientific Reports study at all. They find that nanoparticles from tattoo inks migrate to lymph nodes over time. OK. However, one has to dig to the end of the article to the methods section that comes AFTER the Discussion to discover that these findings are based on a sample of 4 corpses with tattoos and 2 corpses without tattoos. There is no indication of the age of the deceased or how long they had their tattoos. There is no indication of where on the body these tattoos are relative to the lymph nodes. And the word "toxic" is used throughout, which has strong cultural bias. The authors conclude:

The piece that finally got me to sit down and write this is titled "Nanoparticle Scientists Warned Tattooed Folks." The fact is that, because of hygiene and sanitation practices around professional tattooing in much of the world, infection is exceedingly rare. The exceptions get all the press. This title alone feeds into the mysticism of nanoscientists and people with doctoral degrees, huge biomedical grants, and big expensive toys as having access to a deeper insights on the human condition. Furthermore, the warning to "tattooed folks" plays into the cultural narrative that tattooed people are a monolithic group that need protection. I may be overreacting in the this latter evaluation somewhat, but the implication is there, at least in part. I appreciated the podcast interviewer's question to lead author Ines Schreiver, asking her if she actually has any tattoos (I will keep looking for this and provide a link). Whether or not she has them is immaterial, but the way she deflected the question and gave the impression that she does not have any was telling. It suggests to me that she is dismissing the cultural context and meaning tattoos have to make a case for an objective scientific study. There is no complete objectivity in science and even less when we try to disconnect it from context and avoid hidden but potential meaningful variables, like who these corpses were, where on their bodies their tattoos are, and how long they've had them---frankly, these are basic and shamefully overlooked demographic factors. So, I am more concerned with what is not discussed about the corpses than the researchers, but scientific agendas matter. This study doesn't yet tell us much, as this CBCNews piece points out. I'm glad that we are applying neuroscience approaches to cultural practices, but a neuroanthropological approach is warranted in studying tattooing. There is no link between tattooing and disease, disorder, or death in any of these corpses. There is limited evidence that tattoos can cause some reactions in some people. My lab has an as yet unpublished epidemiological study of tattooing, piercing, and adverse reactions in athletes, following up on two studies (2002 and 2008) at Pace University by the late Lester Mayers and colleagues. The rates of adverse reactions reported by respondents in all of these studies is extremely low, and our study sampled over 1000 people from around the US. Sometimes my tattoos raise up on my skin and itch. This experience is common among tattooed people I have talked to. But is it adverse? I have injuries from playing sports going back to when I was a child that act up. I am frequently sore from going to the gym, but I just need to be careful. Skin response to pigments is worth investigating, but the framing of this scientific article and some of the media coverage leave much to be desired. I have some experience with this. On the other end of the spectrum, my colleagues and I conducted a small study of the health benefits of tattooing a few years ago. We found that the stress of tattooing MAY prime the immune system. We framed our interpretation in evolutionary signaling and allostasis theory in that article and in a book chapter that makes hypotheses about the signaling functions of tattoos for athletes and fans. The press ate it up and widely reported that, essentially, tattoos are good for you. Except for Jezebel. Caroline Weinberg interviewed me about our study and wrote a measured piece titled "How One Study Produced a Bunch of Untrue Headlines About Tattoos Strengthening Your Immune System." It is no wonder the public does not know what to believe when it comes to scientific recommendations and health. It is hard to go into the weeds on these studies if one is not an expert. The devil is in the details, and they are exceedingly hard to discern. The public needs to trust us, but it is obvious why they don't. I am saying tattoos can be beneficial. These scientists are saying tattoos can be toxic. Who is right? The truth is in the middle and linked to context. Let's be honest and say that the benefits are probably negligible for the everyday and so are the detriments. These factoids are interesting for scientists but have few implications for everyday people the way they are reported. They are most likely additive benefits and detriments that may even cancel each other out within a contingent biocultural context that is a diverse as are humans. That is not to say these studies are not important and should not be reported. I think that understanding the biology of tattooing can have implications for understanding the immune system better. I think there's a link between the priming effect we think we see, autoimmune disease, and the hygiene hypothesis. But I don't think this is related to tattooing alone. Tattooing is one cultural practice that may stimulate immune function, but there are others. We can examine these biocultural interactions to better understand human health in context. But without context, we are just in spin city.

0 Comments

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed