|

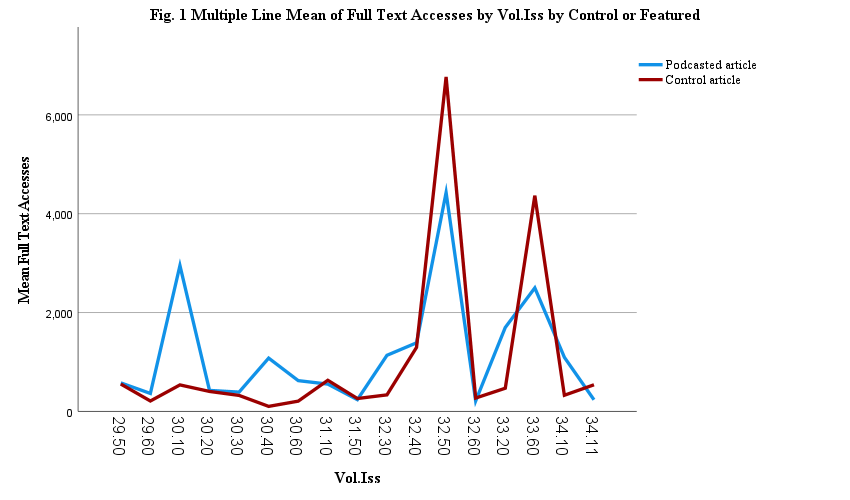

Our lab has new publications! The first is an article about podcasting, written by me with Courtney Manthey and Cara Ocobock. We compared listens to episodes of the Sausage of Science podcast that were highlighted on the pod to those that weren't from the same issues and, save for COVID outliers that were accessed at extraordinarily high rates, podcasted articles were significantly more likely to be accessed. This is good news for academic podcasters! Check it out while it's open access: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajhb.24105

0 Comments

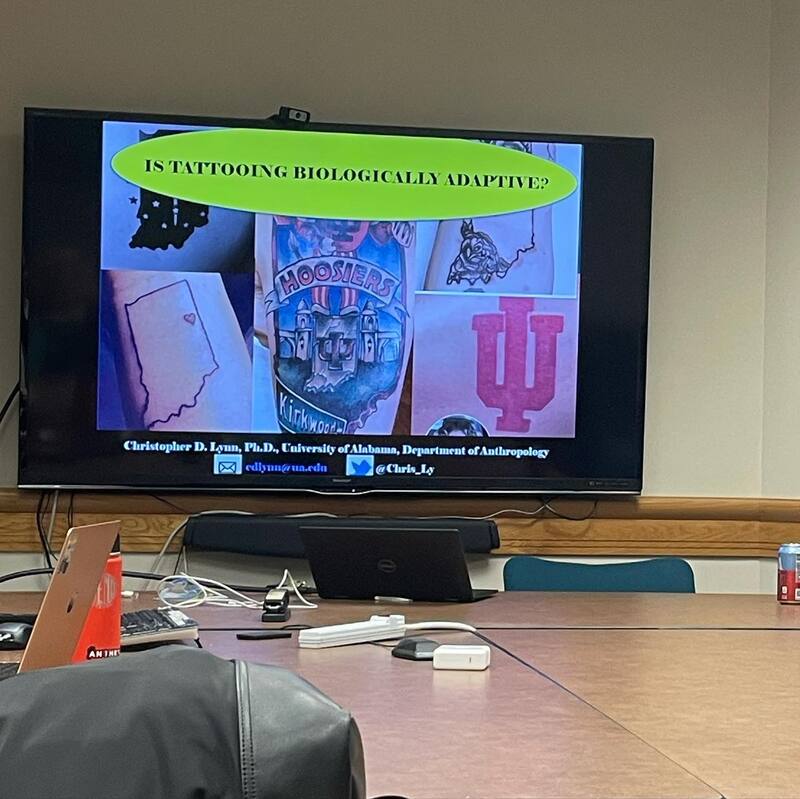

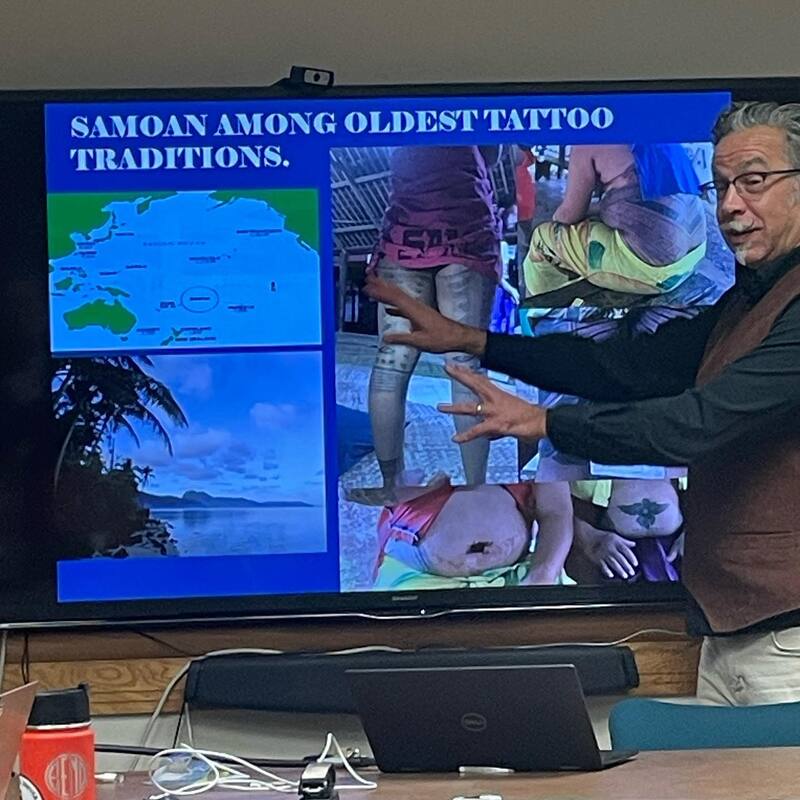

In 2019, I was one of the last cohorts of fellows for the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) Leshner Fellowship for Public Engagement. I thank my friend and colleague Dr. Julie Lesnik for recommending this program to me and me to this program. The program was designed for mid-career professionals and helped me and other fellows take another step up from what we've achieved in our careers and efforts at public engagement. We thought we were ahead of the game, but we learned what more we could do and that publicly engaged scholarship is a discipline and not just something I thought I could do because I can talk to a public audience. The requirements of the Leshner Fellowship were to administer a public engagement project related to our research and another for a scientific institution (usually our own university). I developed a documentary project about tattooing in Samoa and proposed to develop tenure and promotion guidelines at my university for evaluation public engagement.  Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. In 2021, I received a Provost Faculty Leadership Fellowship from UA to develop the T&P project, and this past year we piloted the Public Engagement Learning Community (PELC). It's been renewed for another year, and the goal of the program is to develop a UA community trained in and supportive of publicly engaged scholarship. A community will support the development of public engagement initiatives and shepherd scholarship, as well as be available to evaluate dossiers containing significant publicly engaged scholarship. This semester has been a pique experience in publicly engaged scholarship for me in a way that I didn't realize until I started writing this. It really started before the spring because the PELC program began last year. In the fall, we invited several scholars to campus for the workshops, but, ultimately, they became Zoom presentations for one reason or another. These included a recorded interview with Dr. Timothy Eatman from Rutgers, a presentation and discussion with journalist John Hammontree, and a presentation by Collette Cann and Eric DeMeulenaer, authors of The Academic Activist. By contrast, all of our presenters this spring were in-person speakers, which I have always found make more of an impression. We had a Zoom presentation by Tricia Allen in January, but in February we had a visit by Dr. Timothy Shaffer from University of Delaware and visits from Drs. Diane Doberneck and Timothy Eatman in March. Hosting these workshops and learning about the field of publicly engaged scholarship influenced how I approached the talks I gave and meetings I've attended throughout the past month. The week after Dr. Eatman's culminating workshop, I went to Florida Gulf State University to give an invited book talk, went to Reno for the annual meetings of the biological anthropology organizations, gave a book talk in Birmingham for a bar audience, and went back to my homeland Indiana to give a series of all of my talks. The lesson for all of the talks I gave throughout April as a publicly engaged scholar is to invite oneself to give talks. When I worked in the music industry, bands didn't get record deals or make any money if they didn't tour and promote themselves and their records. In academia, we put books out via academic publishers and rely on those publishers to get our books into university libraries. In many cases, academic books are neither written for nor available to a general audience. In my own publishing experience, my sole authored book that I've been promoting is print on demand. I think this means there are no copies on hand to ship to stores for any urgent demand because when I have tried to order them for my talks, the books are in no hurry to be shipped. The order takes time to process, then the book takes time to be printed and shipped. I am not a fan of this business model. Publisher support aside, invite yourself to give talks. Say you're in the area of a university because your mother paid to bring you home and gave you access to a family car, offer a free talk to the local departments related to your work. This is the best way to recruit graduate students to your program, to introduce potential buyers to your book, and, most importantly, the best way to open up a philosophy of exchanging lectures/faculty expertise between universities. Dr. Anna Osterholtz and I started doing this between Mississippi State University and the University of Alabama. We no longer have anyone specializing in bioarchaeology or skeletal collections to study, but MSU has an expanding program. Conversely, MSU cannot offer more than an MA, but UA offers multiple MA and PhD tracks in anthropology. Invite yourself to give talks because you have something you want to promote. Send a free copy to friends working at other universities. That's what I did to get a talk at FGSU. I sent copies of my book to Drs. Nate Pipitone and Max Stein. Nate and I were in the same evolutionary psychology lab in graduate school, and Max was a graduate student of mine. I didn't ask for a talk, but I probably said I'm available, and Nate offered me one, so we made it happen and I told him about Max. They didn't know each other before they coordinated my talk but are now colleagues. Furthermore, while I was there, I had a bunch of meetings with Nate and Max and their students and came away with multiple potential research collaborations. Think psychedelics and belongingness.  Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. In Reno for the Human Biology Association Annual Scientific Meeting, my undergraduate student Flynn Lewellyn and I presented a poster on publicly engaged scholarship and the Sausage of Science podcast. We left the theory of out the poster, but Flynn and I were determined to tell everyone why our poster is important. I introduced them to Agustin Fuentes and mentioned needing to do something about publicly engaged scholarship in the main forums of our organizations. Agustin is currently battling with millions of trolls on Twitter because of his SciAm post about the non-binariness of sex and non-existence of race, etc. Agustin suggested we do a position paper on this topic, so in my mind, we're now doing a position paper. I put out an informal query about a 2024 session somewhere on publicly engaged anthropology and got a bunch of responses indicating interest, including from the editor of American Anthropologist. And don't just invite yourself for academic talks---find those local Science Cafe or Science on Tap or or whatever they call the "grog talk" program that probably exists in a town near you. They are programs that host academic talks in bar/restaurants. If you can't find one, start one! They are a great way to meet local business owners who share similar values and other academics who like talking with a beer in hand. Last fall I was invited to be one of the initial speakers for the Discourse Birmingham series, hosted at local bars in Birmingham. I gave a tattoo talk in the fall at Monday Night Brewing Company, and it went really well. I felt great about the talk, and the hosts Lawrence and Janek invited me back for another talk this spring at Rojo. This gave me a chance to tweak my book talk for a public audience. I've given public book readings but not yet a public talk on this book, so this was important for me. And, again, I think it went really well; this is based purely on people staying to meet me until the bars closed, and they kicked us out. My mother gave one of my books to her pastor because she thought it would be of interest to her church congregation. The Garden is one of those churches that has a roughly Christian template but is mostly about communing with other humans, having a sense of a Higher Power that loves everyone, and community service. My mom likes that the pastor emphasizes messages that resonate with modern life and keeps services short. The pastor likes the book because it's interesting and, as she pointed out several times, the only academic book that's made her laugh out loud. She and my mother arranged to have me speak this past Sunday as what was in fact the main talk of the service, and my mother paid to bring me up. I talked about fireside relaxation, spiritual transcendence, and the biology of self-soothing. Since the trip was paid for, I'd be able to stay at my parents' place and have access to their vehicle for free, I offered myself up for free lectures to anthropology departments at other nearby universities. I wanted it to be worth the effort for me to travel and my mother to pay for me, so I reached out to people I already know. I've been active in professional organizations since I started graduate school and cohost a weekly science podcast, so, among other reasons, I know a fair amount of people I can reach out to. I got in touch with colleagues at several Indiana universities and managed to book a tattoo talk at Indiana University on Monday and a public engagement talk at Purdue on Tuesday. I went to IU right out of high school for my first two years of college. It wasn't in anthropology, but that was still cool and special for me. I gave a tattoo talk and met another anthropology professor who's been tasked with teaching the "anthropology of sex, drugs, and rock'n'roll." I may have dropped Paul Mahern's name, who I only know personally thru Facebook but whose band was the first punk rock show I ever saw. Mahern is lead singer of The Zero Boys, Indiana's first and best hardcore punk band. He has been a recording engineer, producer, and studio owner for 30 years, and is now also a college educator. I gave a talk about publicly engaged anthropology and how to make it count at Purdue on Tuesday. I offered them one of my usual talks, but I know enough people at Purdue who know enough about me that they asked for a different talk. They asked for a talk about my public engagement, such as my podcast... So I took the opportunity to combine the workshop I've been running with my discipline to give tips specific for an anthropology department with a similar scope to the one I'm in. While there, I met with Kari Guilbault, a bioarchaeology student who has been conducting an MA study of Nubian mummy tattoos. We had communicated before COVID19 and I offered a talk to Purdue if I could ever get to my folks during the academic semester (only an hour from my parents' house, so a low-stress offer). It was useful to workshop this new talk for my friend and primary host Dr. Melanie Beasley. Melanie and I have gotten to know each other through biological anthropology professional organizations over the course of our careers. Their department included me as part of their Anthropologies of Tomorrow series and thanked me for inviting myself, because departments also become too busy too organize their funded speaker series. Colleges and departments provide funding for such series, but departments often forego these opportunities because faculty feel or are over-serviced. As a publicly engaged scholarly, these are the types of opportunities I foster (as host) at my own university and seek out via others' programs. Melanie gave me some good advice on how to flesh out the slides to make my points; and I realized I can integrate more of my projects as examples in ways I hadn't thought of previously. I haven't mentioned making it count. What I mean by that is academics need to justify this publicly engaged work as scholarship to get institutional recognition and protection for it. As my friend and colleague Drew Pearl said this year in probably the more profound statement I heard through our tutelage of the PELC program, "universities are structural institutions and inherently conservative, but the faculty tend to be progressive," or something to that effect. Boom. Mic drop.

But not really. Since they are conservative, we have to meet them halfway by developing ways to measure public engagement and turn it into peer-reviewed scholarship, which is the coin of the realm. The examples I use in this talk include our recent efforts to measure the impact of the podcast and turn the #Hackademics series into a special issue but the many retrofitted articles I've written about public programs I've developed or events I've been involved with. This, I suspect, will be the basis for a position paper... The Human Biology Association & American Association of Biological Anthropology annual meetings were held at the Peppermill Resort and Spa in Reno, Nevada this year. Technically, I should list the AABA first because they are the primary sponsor and organizer of the conference. However, I am more active in the HBA and attend more HBA functions, so I set it first in my report.

The Peppermill was an interesting choice. I was looking forward to the excitement of being in a resort hotel for nearly a week, but it wasn't really what I expected. People kept joking that it was a Cheesecake Factory on steroids. However, it will have been memorable, and it was a great conference with excellent presentations, interested students, and fun and creative conversations! As a member of the HBA Executive Committee, we had a dinner/meeting the first night to prep for the business meeting, and otherwise I hung out with friends/colleagues Eric Shattuck, Cara Ocobock, and Saige Kelmelis. On Wednesday was the the HBA poster session, plenary, Pearl Memorial Lecture, and HBA Awards Reception. HBERG students Flynn Lewellyn (undergraduate senior) and Lindsey Clark (doctoral student) presented on public engagement via the Sausage of Science Podcast and the Fireside Relaxation Study, respectively. Thursday was sessions, the HBA Business Meeting, and the Student Speednetworking Reception. There was hanging out in a lounge with live Americana music. There was also a brief attempt to warm up in the outdoor heated pool that backfired, then we went to the AABA Reception. Friday were the flashtalks in which I presented as the end of the HBA conference. There were AABA sessions all day, the the AABA Business Meeting and Awards Ceremony. My dear friend and colleague Cara Ocobock won a Leakey Foundation Award for Science Communication at the meeting and gave a lovely speech. I may have gotten choked up. Cara invited me as her +1 to mingle with the AABA Executive Committee and awardees for snacks and beverages. The conference lasted through Saturday, but I left on Saturday, along with many of those I was hanging out with. My cohost Cara Ocobock and I brought two new producers on this season and have produced new episodes with Andrea Silva-Caballero, Amanda Veile, Rachael Anyim, Zachary Cofran, Natalia Reagan, and Lara Durgavich. The producers, Cristina Gildee, a doctoral student at the University of Washington, and Eric Griffith, a postdoc at Duke who got his PhD from UMass under Lynnette Sievert. The Sausage of Science producers are supported as Junior Service Fellows of the Human Biology Association and the American Journal of Human Biology. Subscribe to the Sausage of Science on Soundcloud or wherever you get podcasts (except Spotify apparently [deep sigh]}.

Dr. Alyssa Crittenden joins the Sausage of Science podcast for an excellent conversation (despite internet connectivity issues) about her work with Hadza community members, community-based work, and reconsidering biological sample collection. You can find her recent paper “Who Owns Poop? and Other Ethical Dilemmas Facing an Anthropologist Who Works at the Interface of Biological Research and Indigenous Rights” digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/anthro_fac_…ticles/590/. Dr. Alyssa Crittenden is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. You can contact her via her website: www.unlv.edu/people/alyssa-crittenden and on Twitter: @an_crittenden

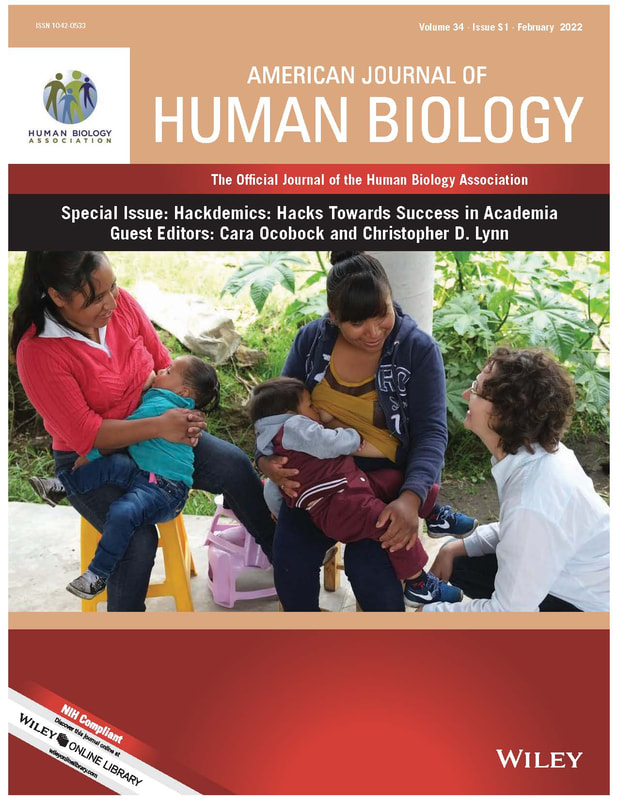

Contact the Sausage of Science Podcast and Human Biology Association: Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/humanbiologyassociation Website:humbio.org/, Twitter: @HumBioAssoc Dr. Cara Ocobock and I are proud to announce the official publication of the #Hackademics Special Issue of American Journal of Human Biology that we co-edited!

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15206300/2022/34/S1... All articles are #openaccess for the next 3 months and relevant across academia. In this issue you will find:

My cohost Cara Ocobock from Notre Dame & I have started our 4th year of the weekly Sausage of Science podcast for the Human Biology Association & American Journal of Human Biology. We started this year interviewing Mississippi State bioarchaeologist Dr. Anna Osterholtz. Follow this link below to listen to us chat with her about the ethics & poetics (yes, poetry of the dead) of working with human remains. Be sure to subscribe, like, rate, blah blah to keep up with our weekly interviews with human biologists & human bio-adjacent scholars!

It's hard to keep up with everything going on around here, but the Human Biology Association publishes a podcast every other week that I co-host with Dr. Cara Ocobock from SUNY Albany. The newest episode "When It Rains, It Floods," with Dr. Asher Rosinger from Penn State is just up. This was a great conversation!

Check out all our episodes, including interviews with Mallika Sarma, Alex Brewis, Jo Weaver, Lynnette Sievert, Isa Godinez, Kathy Oths, Hannah Smith, Bill Leonard, Rieti Gengo, Andrea Wiley, Joe Graves, Mary Shenk, Siobhan Mattison, Morgan Hoke, Liz Holdsworth, Larry Schell, Sharon DeWitte, Nina Jablonski, and Sean Rafferty. I was heartened this week by conversations with visiting ALLELE lecturer Nina Jablonski, one of the world's foremost experts on skin biology and evolution. I was glad to see that she discussed tattooing in her 2006 book Skin: A Natural History, though she did not go deep on the biology of tattooing. One reason is that there is not much out there about the biology of tattooing that is not essentially alarmist and negative. What heartened me is that she said she gets a lot of queries about tattooing that are beyond her expertise and interest and that she will start referring the (non-quack) queries to me. Which made me realize I'm something of a expert, having conducted one study on the biology of tattooing, read a lot about it, and currently conducting another in the South Pacific with my main collaborator Michaela Howells.  Interviewing Nina Jablonski for "Sausage of Science" and "Science of Race" podcasts with Jim Bindon, Erik Peterson, & Jo Weaver (taking the picture). Interviewing Nina Jablonski for "Sausage of Science" and "Science of Race" podcasts with Jim Bindon, Erik Peterson, & Jo Weaver (taking the picture).

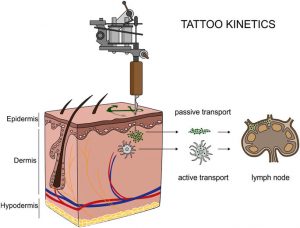

That recognition obliges me to speak up about the study just out in Scientific Reports (a Nature journal) that I have been sent press links about in the last several days. I heard one of the researchers speak about the study on a podcast I listen to regularly (I think BBC World Serivce but can't relocate at moment) and was not impressed. The gist of the study is that tattooing has become extremely popular, but the inks are understudied as toxicants. I beg to differ. The potential dangers of tattoo inks is in fact among the most reported on and studied aspects of tattooing addressed in the biomedical literature, alongside the correlations between tattooing and risk behavior (which is a cultural phenomenon, with little to do with the biology of tattooing aside from the signaling function it serves). < href="http://evostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1-2.jpg"> Translocation of tattoo particles from skin to lymph nodes. Upon injection of tattoo inks, particles can be either passively transported via blood and lymph fluids or phagocytized by immune cells and subsequently deposited in regional lymph nodes. After healing, particles are present in the dermis and in the sinusoids of the draining lymph nodes. The picture was drawn by the authors (i.e., C.S.).1SCIentIFIC REPORTS | 7: 11395 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11721-z[/caption] Translocation of tattoo particles from skin to lymph nodes. Upon injection of tattoo inks, particles can be either passively transported via blood and lymph fluids or phagocytized by immune cells and subsequently deposited in regional lymph nodes. After healing, particles are present in the dermis and in the sinusoids of the draining lymph nodes. The picture was drawn by the authors (i.e., C.S.).1SCIentIFIC REPORTS | 7: 11395 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11721-z[/caption]

The fetishism of tattooing in Euroamerican culture over the past few decades is reflected in the alarmist focus of the dermatological literature. Mind you, I don't dispute the findings of the researchers this this Scientific Reports study at all. They find that nanoparticles from tattoo inks migrate to lymph nodes over time. OK. However, one has to dig to the end of the article to the methods section that comes AFTER the Discussion to discover that these findings are based on a sample of 4 corpses with tattoos and 2 corpses without tattoos. There is no indication of the age of the deceased or how long they had their tattoos. There is no indication of where on the body these tattoos are relative to the lymph nodes. And the word "toxic" is used throughout, which has strong cultural bias. The authors conclude:

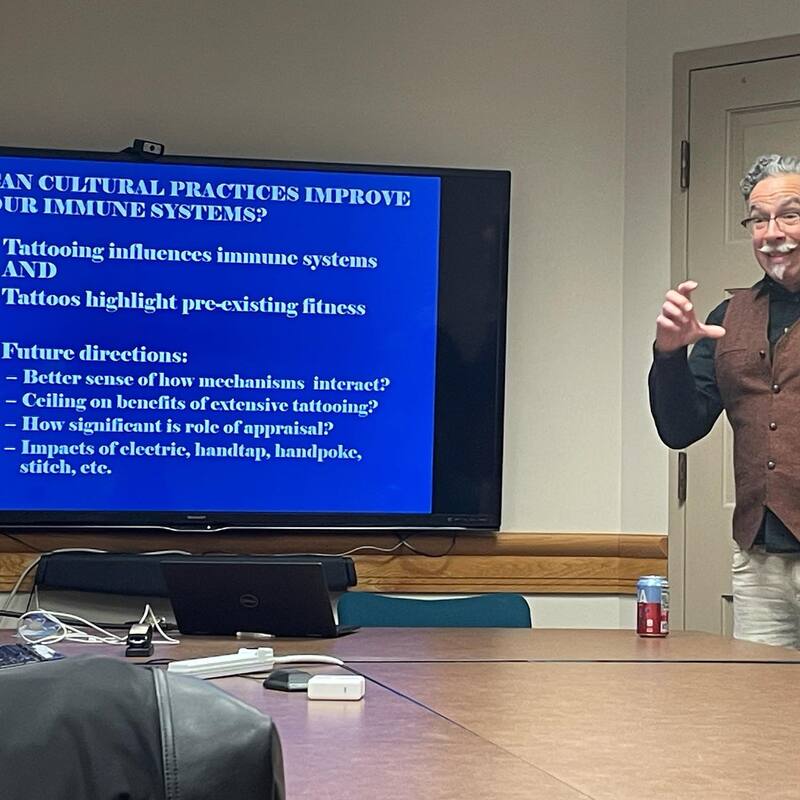

The piece that finally got me to sit down and write this is titled "Nanoparticle Scientists Warned Tattooed Folks." The fact is that, because of hygiene and sanitation practices around professional tattooing in much of the world, infection is exceedingly rare. The exceptions get all the press. This title alone feeds into the mysticism of nanoscientists and people with doctoral degrees, huge biomedical grants, and big expensive toys as having access to a deeper insights on the human condition. Furthermore, the warning to "tattooed folks" plays into the cultural narrative that tattooed people are a monolithic group that need protection. I may be overreacting in the this latter evaluation somewhat, but the implication is there, at least in part. I appreciated the podcast interviewer's question to lead author Ines Schreiver, asking her if she actually has any tattoos (I will keep looking for this and provide a link). Whether or not she has them is immaterial, but the way she deflected the question and gave the impression that she does not have any was telling. It suggests to me that she is dismissing the cultural context and meaning tattoos have to make a case for an objective scientific study. There is no complete objectivity in science and even less when we try to disconnect it from context and avoid hidden but potential meaningful variables, like who these corpses were, where on their bodies their tattoos are, and how long they've had them---frankly, these are basic and shamefully overlooked demographic factors. So, I am more concerned with what is not discussed about the corpses than the researchers, but scientific agendas matter. This study doesn't yet tell us much, as this CBCNews piece points out. I'm glad that we are applying neuroscience approaches to cultural practices, but a neuroanthropological approach is warranted in studying tattooing. There is no link between tattooing and disease, disorder, or death in any of these corpses. There is limited evidence that tattoos can cause some reactions in some people. My lab has an as yet unpublished epidemiological study of tattooing, piercing, and adverse reactions in athletes, following up on two studies (2002 and 2008) at Pace University by the late Lester Mayers and colleagues. The rates of adverse reactions reported by respondents in all of these studies is extremely low, and our study sampled over 1000 people from around the US. Sometimes my tattoos raise up on my skin and itch. This experience is common among tattooed people I have talked to. But is it adverse? I have injuries from playing sports going back to when I was a child that act up. I am frequently sore from going to the gym, but I just need to be careful. Skin response to pigments is worth investigating, but the framing of this scientific article and some of the media coverage leave much to be desired. I have some experience with this. On the other end of the spectrum, my colleagues and I conducted a small study of the health benefits of tattooing a few years ago. We found that the stress of tattooing MAY prime the immune system. We framed our interpretation in evolutionary signaling and allostasis theory in that article and in a book chapter that makes hypotheses about the signaling functions of tattoos for athletes and fans. The press ate it up and widely reported that, essentially, tattoos are good for you. Except for Jezebel. Caroline Weinberg interviewed me about our study and wrote a measured piece titled "How One Study Produced a Bunch of Untrue Headlines About Tattoos Strengthening Your Immune System." It is no wonder the public does not know what to believe when it comes to scientific recommendations and health. It is hard to go into the weeds on these studies if one is not an expert. The devil is in the details, and they are exceedingly hard to discern. The public needs to trust us, but it is obvious why they don't. I am saying tattoos can be beneficial. These scientists are saying tattoos can be toxic. Who is right? The truth is in the middle and linked to context. Let's be honest and say that the benefits are probably negligible for the everyday and so are the detriments. These factoids are interesting for scientists but have few implications for everyday people the way they are reported. They are most likely additive benefits and detriments that may even cancel each other out within a contingent biocultural context that is a diverse as are humans. That is not to say these studies are not important and should not be reported. I think that understanding the biology of tattooing can have implications for understanding the immune system better. I think there's a link between the priming effect we think we see, autoimmune disease, and the hygiene hypothesis. But I don't think this is related to tattooing alone. Tattooing is one cultural practice that may stimulate immune function, but there are others. We can examine these biocultural interactions to better understand human health in context. But without context, we are just in spin city. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed