|

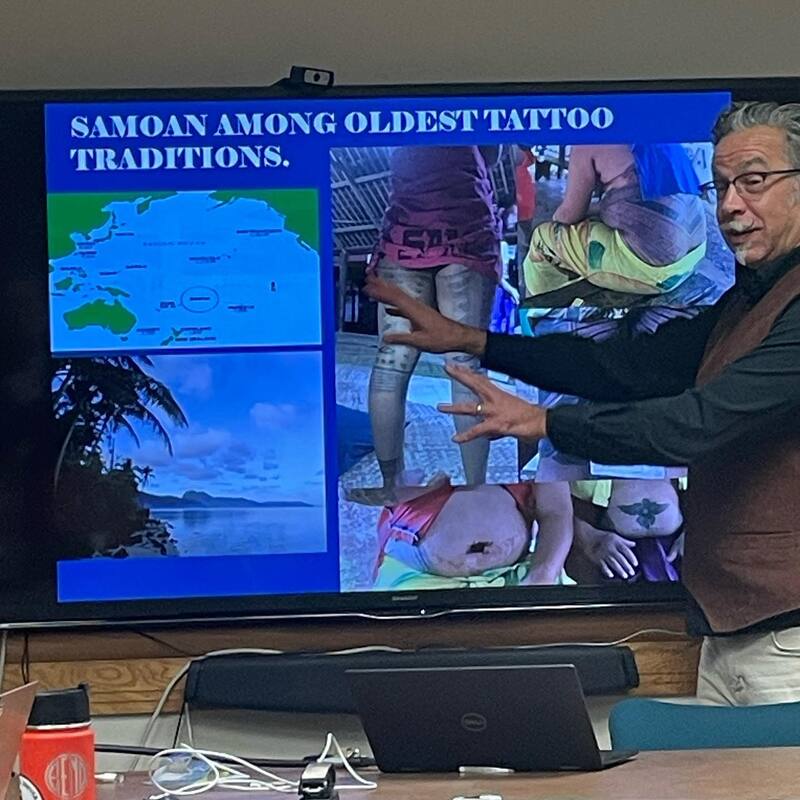

We have a new article out in Pacific Journal of Health that explores a case study of tatau. We collected cortisol throughout multiple days for a man getting a Samoan pe'a tattoo. This is the first documentation of the physiological response to traditional tattooing that we know of. Read the full open access text here.

0 Comments

We also have a brand new chapter on the medical anthropology of tattooing in the Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification. This was co-authored with former graduate student Michael Smetana. Mike wrote the first draft for a course, and I slogged away on the rest of it over the course of a year or two. Marco Samadelli wrote a short summary and didn't have time to write a full chapter, so they asked me to combine his chapter with ours. I'm quite pleased with it, though I've already found a few things that will need to be fixed if they retain it for future editions. Check it out here.

Saturday, July 22, 2023On Saturday, I was supposed to get a tattoo at 9am from Joe at Off Da Rock. I'd been planning to get one from him in 2017 when we worked together on my second tattoo study, but I'd had to return home early due to a family emergency and hadn't seen him since. The problem at the time was that Samoa and American Samoa don't play nice in a lot of ways, including the cell phone carriers they use. American Samoa used to be Digicel and Blue Sky, with Blue Sky being the only carrier that works in both countries. So of course when I was in American Samoa the first time, I bought a Digicel phone (bad advice). I skipped getting a Samoan phone until this year, when I bought a phone with Bluesky. Well, apparently Bluesky was sold, and they're no longer compatible in both countries. Or something. So I could only get messages via email and social media, and Joe doesn't really use email. So he wasn't able to tell me when he was running late. I slept in the car in front of his shop for about an hour before one of the seamstresses from his adjacent clothing shop knocked on my window to tell me he needed to reschedule. I went back to find Josh up an roaming around the hotel grounds talking to his girlfriend on his phone and Grant laid out with a fever. I wasn't feeling great myself, so I laid back down and was out until about midafternoon. We essentially did nothing the rest of Saturday except hang out and probably watch some Women's World Cup Soccer. Sunday, July 23Sunday was similar. We all felt like shit, but I kept trying to rally us to show the guys around Tutuila a bit. It's so weird to be in American Samoa for the first time since 2017 and after several trips to Samoa. Because one was colonized by the US and the other by New Zealand, I feel more at home in American Samoa. Ironically, the facilities and resources of American Samoa are better, as indicated by the illness we suffered all week. Grant was really ailing, and it was coming on Josh, so we didn't end up doing much. I took them for a drive to see the Vai'ava Strait National Natural Landmark because it's on the other side of the mountain range that runs thru Tutuila, and I hadn't been there before. The photos below remind me of how cool it is but also of a skinny little dog that followed us from the village up the rocky road to the parking lot, onto the beach, and back again. It actually let us pet it, which is unusual of Samoan dogs. Monday, July 24On Monday we were similarly laid out. However, I'd asked Leota if he could ask his sister in American Samoa could help us meet people to interview. Consequently, she arranged for the church youth group she works with to participate. They were happy to have the compensation for participation to donate to the youth group fund. We all felt so sick all day that we half hoped it wouldn't happen, but we also had been ailing so much that we had not been able to chase down other leads. Leota also wanted us to be able to get our sample early and enjoy ourselves for a few days, so he was anxious to help us finish. The tough part for us, given our queasy stomachs, was that the youth group met in a fale tele overlooking the tuna canneries! It's steep, gritty part of American Samoa full of immigrants who work the canneries, and it stinks when the wind is blowing in the wrong direction. Fortunately, we all weathered it and had a splendid evening of data collection. The principle of unconstrained pile sorting in the manner we conducted this study is that each person is given 50 cards with a Samoan term on one side and the English translation and number on the other side. The terms were developed during the freelisting stage described earlier. They are told that the cards are terms that describe typical Samoanness and that the terms come from Samoans in Samoa and Hawaii. They are asked to sort the cards into meaningful piles and to give each pile a name. The only other rules are that there have to more than 1 pile and fewer than 50. Participants enjoyed this research activity. They felt it was more like a game than just a survey and had fun doing it with their friends. There were high degrees of overlap in pile sorts among people hanging out together at the time of data collection but also between each of these groups, suggesting we're going to find a high statistical degree of sharing in the themes too. We can certainly explain some of this as the influence of others in the room, but we were also surprised at how different the piles of people who were friends could be. Leota had been shocked by the variation he observed among his extended family. After collection data, we stayed for a birthday celebration of one of the youth group adult members and ate cake before heading back to Sadie's, thoroughly satisfied with a blessed evening, as they say. Tuesday, July 25On Tuesday, Leota's sister Ake wanted to take us out to dinner. We were going to be treated to dinner by the whole family. I think originally they were going to put something together Samoan style, but they toggled to American style by having it at the local fancy Chinese place, we were fine. We weren't sure we had the stamina for more Samoan-style hospitality, and I'd been to this restaurant numerous times, so it was a good call. As it turned out, meeting Leota's family in American Samoa is as much an epitome of the contemporary relationships between the countries as anything. We expected the traditional Samoan treatment we'd received in Savai'i, and instead we discovered Leota's father and grandparents here were quintessentially multi-cultural American family, with a mixed heritage of Samoan, Chinese, Fijian, and American.

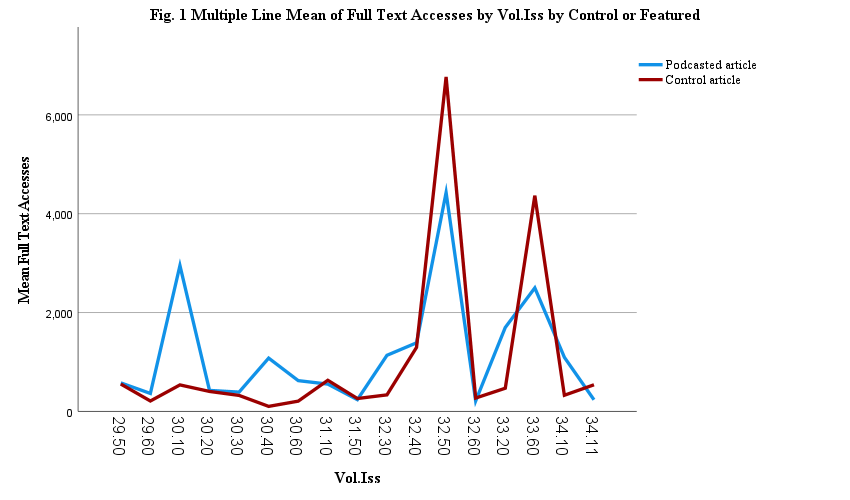

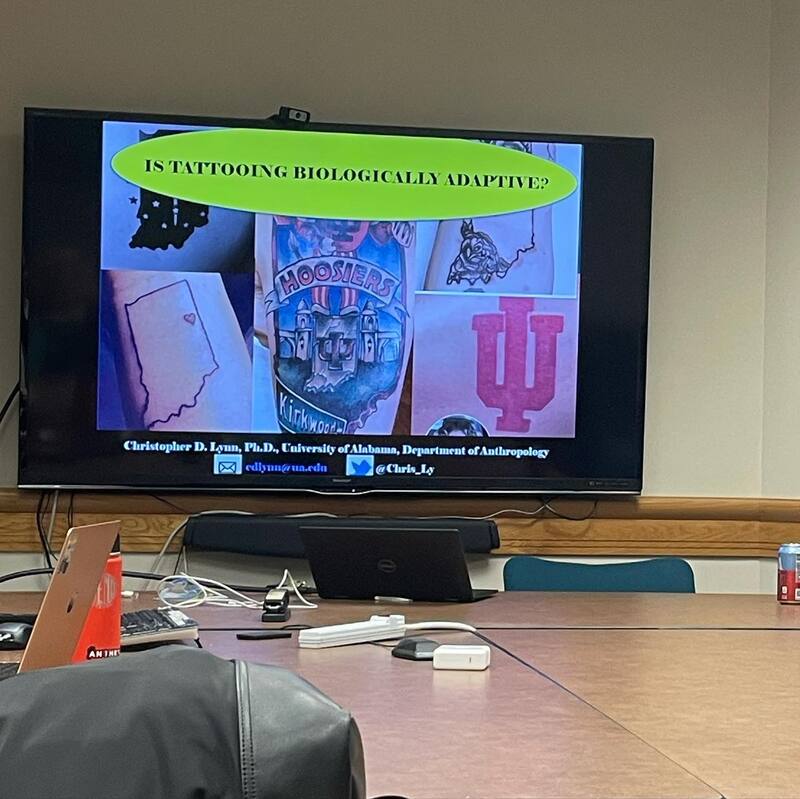

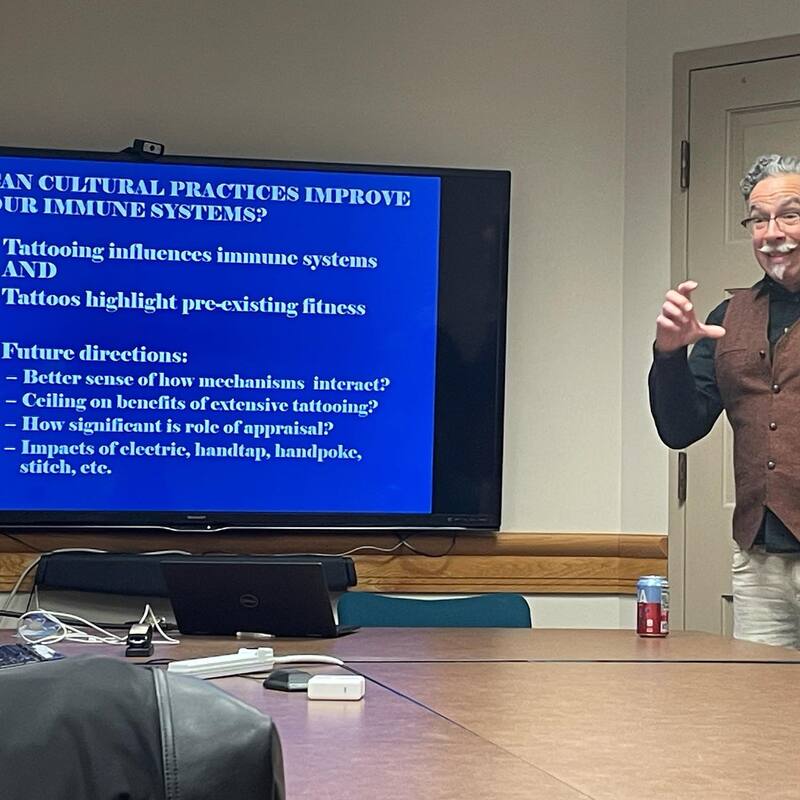

Pulling together a chicken stir-fry in our makeshift kitchen. Pulling together a chicken stir-fry in our makeshift kitchen. Undergraduate research assistant Grant Pethel and I were supposed to arrive in Apia, Samoa on Thursday, and on Friday we were going to meet with collaborator Dr. Bernadette Samau from the National University of Samoa. We were in a bit of a time crunch because Bernie was leaving the following week for her own summer research trips, and we needed to finalize our research methods for this summer. More on that later. But because of our flight delays, we didn't arrive until Friday afternoon, so we just kind of took the weekend to get settled (and find clothes--see previous post). And I always try to fit in a weekly cultural excursion when I'm doing fieldwork, especially with students. One of the main Baha'i Temples in the world is in Samoa, which we learned by visiting it. I'd seen it on previous trips, as it's a giant temple overlooking Apia that is clearly visible when crossing the Cross-Island road, and tourists see it on the way up to the Robert Louis Stevenson Museum. This is my fourth time in Samoa but first time visiting the Bahai'i Temple. Grant and I wandered the meditative grounds, read about the architectural design of the temple, which resembles a Samoan fale. And we visited the grave of one of the Persian founders of the Baha'i Temple here, who comes from where Baha'i originates. I'm a little murky on the history now, and I lost the brochures we picked up. We mostly grabbed them to read the English to Samoan translations so we could work on our Samoan language skills, but I got caught up in the fascinating history of Baha'i, and the temple here in Samoa. Here is a link to the temple in Samoa, which contains the history of this temple and a bit on the history of Baha'i which I guess I can look up on the internet too, so here is a link to a reputable source on Bahai. We finished the day by assembling our makeshift kitchen to make some chicken stir-fry. Adjusting to local spices and food availability is interesting. In 2019, I was one of the last cohorts of fellows for the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) Leshner Fellowship for Public Engagement. I thank my friend and colleague Dr. Julie Lesnik for recommending this program to me and me to this program. The program was designed for mid-career professionals and helped me and other fellows take another step up from what we've achieved in our careers and efforts at public engagement. We thought we were ahead of the game, but we learned what more we could do and that publicly engaged scholarship is a discipline and not just something I thought I could do because I can talk to a public audience. The requirements of the Leshner Fellowship were to administer a public engagement project related to our research and another for a scientific institution (usually our own university). I developed a documentary project about tattooing in Samoa and proposed to develop tenure and promotion guidelines at my university for evaluation public engagement.  Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. In 2021, I received a Provost Faculty Leadership Fellowship from UA to develop the T&P project, and this past year we piloted the Public Engagement Learning Community (PELC). It's been renewed for another year, and the goal of the program is to develop a UA community trained in and supportive of publicly engaged scholarship. A community will support the development of public engagement initiatives and shepherd scholarship, as well as be available to evaluate dossiers containing significant publicly engaged scholarship. This semester has been a pique experience in publicly engaged scholarship for me in a way that I didn't realize until I started writing this. It really started before the spring because the PELC program began last year. In the fall, we invited several scholars to campus for the workshops, but, ultimately, they became Zoom presentations for one reason or another. These included a recorded interview with Dr. Timothy Eatman from Rutgers, a presentation and discussion with journalist John Hammontree, and a presentation by Collette Cann and Eric DeMeulenaer, authors of The Academic Activist. By contrast, all of our presenters this spring were in-person speakers, which I have always found make more of an impression. We had a Zoom presentation by Tricia Allen in January, but in February we had a visit by Dr. Timothy Shaffer from University of Delaware and visits from Drs. Diane Doberneck and Timothy Eatman in March. Hosting these workshops and learning about the field of publicly engaged scholarship influenced how I approached the talks I gave and meetings I've attended throughout the past month. The week after Dr. Eatman's culminating workshop, I went to Florida Gulf State University to give an invited book talk, went to Reno for the annual meetings of the biological anthropology organizations, gave a book talk in Birmingham for a bar audience, and went back to my homeland Indiana to give a series of all of my talks. The lesson for all of the talks I gave throughout April as a publicly engaged scholar is to invite oneself to give talks. When I worked in the music industry, bands didn't get record deals or make any money if they didn't tour and promote themselves and their records. In academia, we put books out via academic publishers and rely on those publishers to get our books into university libraries. In many cases, academic books are neither written for nor available to a general audience. In my own publishing experience, my sole authored book that I've been promoting is print on demand. I think this means there are no copies on hand to ship to stores for any urgent demand because when I have tried to order them for my talks, the books are in no hurry to be shipped. The order takes time to process, then the book takes time to be printed and shipped. I am not a fan of this business model. Publisher support aside, invite yourself to give talks. Say you're in the area of a university because your mother paid to bring you home and gave you access to a family car, offer a free talk to the local departments related to your work. This is the best way to recruit graduate students to your program, to introduce potential buyers to your book, and, most importantly, the best way to open up a philosophy of exchanging lectures/faculty expertise between universities. Dr. Anna Osterholtz and I started doing this between Mississippi State University and the University of Alabama. We no longer have anyone specializing in bioarchaeology or skeletal collections to study, but MSU has an expanding program. Conversely, MSU cannot offer more than an MA, but UA offers multiple MA and PhD tracks in anthropology. Invite yourself to give talks because you have something you want to promote. Send a free copy to friends working at other universities. That's what I did to get a talk at FGSU. I sent copies of my book to Drs. Nate Pipitone and Max Stein. Nate and I were in the same evolutionary psychology lab in graduate school, and Max was a graduate student of mine. I didn't ask for a talk, but I probably said I'm available, and Nate offered me one, so we made it happen and I told him about Max. They didn't know each other before they coordinated my talk but are now colleagues. Furthermore, while I was there, I had a bunch of meetings with Nate and Max and their students and came away with multiple potential research collaborations. Think psychedelics and belongingness.  Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. In Reno for the Human Biology Association Annual Scientific Meeting, my undergraduate student Flynn Lewellyn and I presented a poster on publicly engaged scholarship and the Sausage of Science podcast. We left the theory of out the poster, but Flynn and I were determined to tell everyone why our poster is important. I introduced them to Agustin Fuentes and mentioned needing to do something about publicly engaged scholarship in the main forums of our organizations. Agustin is currently battling with millions of trolls on Twitter because of his SciAm post about the non-binariness of sex and non-existence of race, etc. Agustin suggested we do a position paper on this topic, so in my mind, we're now doing a position paper. I put out an informal query about a 2024 session somewhere on publicly engaged anthropology and got a bunch of responses indicating interest, including from the editor of American Anthropologist. And don't just invite yourself for academic talks---find those local Science Cafe or Science on Tap or or whatever they call the "grog talk" program that probably exists in a town near you. They are programs that host academic talks in bar/restaurants. If you can't find one, start one! They are a great way to meet local business owners who share similar values and other academics who like talking with a beer in hand. Last fall I was invited to be one of the initial speakers for the Discourse Birmingham series, hosted at local bars in Birmingham. I gave a tattoo talk in the fall at Monday Night Brewing Company, and it went really well. I felt great about the talk, and the hosts Lawrence and Janek invited me back for another talk this spring at Rojo. This gave me a chance to tweak my book talk for a public audience. I've given public book readings but not yet a public talk on this book, so this was important for me. And, again, I think it went really well; this is based purely on people staying to meet me until the bars closed, and they kicked us out. My mother gave one of my books to her pastor because she thought it would be of interest to her church congregation. The Garden is one of those churches that has a roughly Christian template but is mostly about communing with other humans, having a sense of a Higher Power that loves everyone, and community service. My mom likes that the pastor emphasizes messages that resonate with modern life and keeps services short. The pastor likes the book because it's interesting and, as she pointed out several times, the only academic book that's made her laugh out loud. She and my mother arranged to have me speak this past Sunday as what was in fact the main talk of the service, and my mother paid to bring me up. I talked about fireside relaxation, spiritual transcendence, and the biology of self-soothing. Since the trip was paid for, I'd be able to stay at my parents' place and have access to their vehicle for free, I offered myself up for free lectures to anthropology departments at other nearby universities. I wanted it to be worth the effort for me to travel and my mother to pay for me, so I reached out to people I already know. I've been active in professional organizations since I started graduate school and cohost a weekly science podcast, so, among other reasons, I know a fair amount of people I can reach out to. I got in touch with colleagues at several Indiana universities and managed to book a tattoo talk at Indiana University on Monday and a public engagement talk at Purdue on Tuesday. I went to IU right out of high school for my first two years of college. It wasn't in anthropology, but that was still cool and special for me. I gave a tattoo talk and met another anthropology professor who's been tasked with teaching the "anthropology of sex, drugs, and rock'n'roll." I may have dropped Paul Mahern's name, who I only know personally thru Facebook but whose band was the first punk rock show I ever saw. Mahern is lead singer of The Zero Boys, Indiana's first and best hardcore punk band. He has been a recording engineer, producer, and studio owner for 30 years, and is now also a college educator. I gave a talk about publicly engaged anthropology and how to make it count at Purdue on Tuesday. I offered them one of my usual talks, but I know enough people at Purdue who know enough about me that they asked for a different talk. They asked for a talk about my public engagement, such as my podcast... So I took the opportunity to combine the workshop I've been running with my discipline to give tips specific for an anthropology department with a similar scope to the one I'm in. While there, I met with Kari Guilbault, a bioarchaeology student who has been conducting an MA study of Nubian mummy tattoos. We had communicated before COVID19 and I offered a talk to Purdue if I could ever get to my folks during the academic semester (only an hour from my parents' house, so a low-stress offer). It was useful to workshop this new talk for my friend and primary host Dr. Melanie Beasley. Melanie and I have gotten to know each other through biological anthropology professional organizations over the course of our careers. Their department included me as part of their Anthropologies of Tomorrow series and thanked me for inviting myself, because departments also become too busy too organize their funded speaker series. Colleges and departments provide funding for such series, but departments often forego these opportunities because faculty feel or are over-serviced. As a publicly engaged scholarly, these are the types of opportunities I foster (as host) at my own university and seek out via others' programs. Melanie gave me some good advice on how to flesh out the slides to make my points; and I realized I can integrate more of my projects as examples in ways I hadn't thought of previously. I haven't mentioned making it count. What I mean by that is academics need to justify this publicly engaged work as scholarship to get institutional recognition and protection for it. As my friend and colleague Drew Pearl said this year in probably the more profound statement I heard through our tutelage of the PELC program, "universities are structural institutions and inherently conservative, but the faculty tend to be progressive," or something to that effect. Boom. Mic drop.

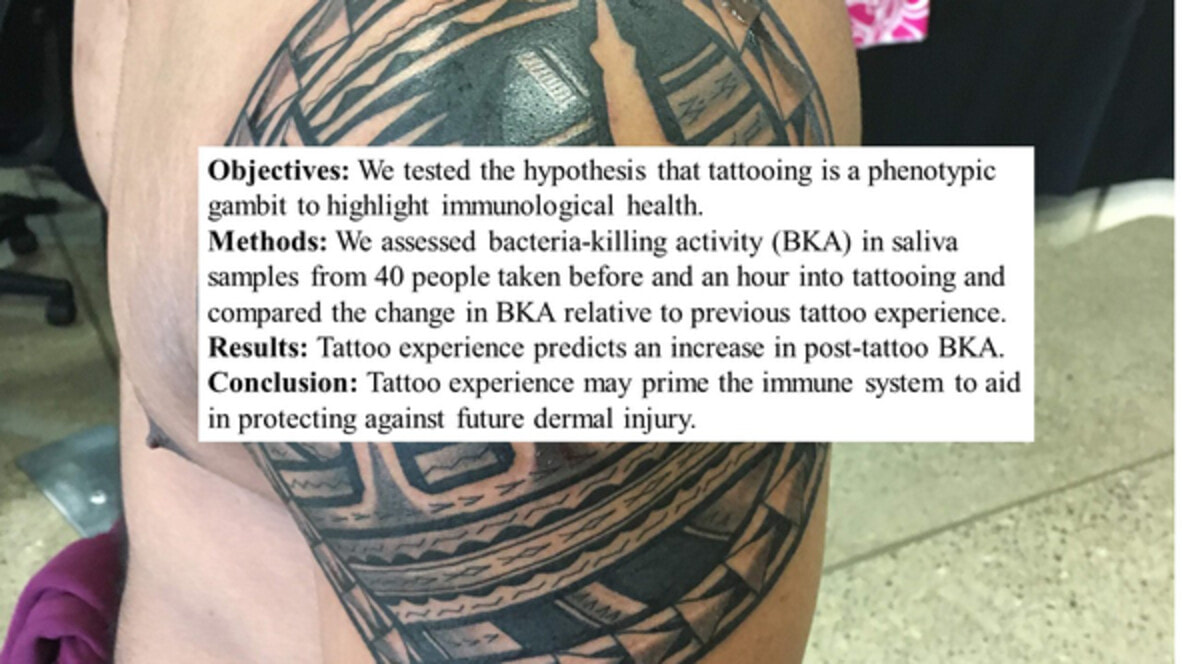

But not really. Since they are conservative, we have to meet them halfway by developing ways to measure public engagement and turn it into peer-reviewed scholarship, which is the coin of the realm. The examples I use in this talk include our recent efforts to measure the impact of the podcast and turn the #Hackademics series into a special issue but the many retrofitted articles I've written about public programs I've developed or events I've been involved with. This, I suspect, will be the basis for a position paper... Another nice piece recently came about tattooing and immune function that I was interviewed for. This one is in Parade Magazine:

https://parade.com/health/tattoos-immune-system  American Journal of Biological Anthropology is essentially the flagship journal of US bioanth, yet until this publication I've never even submitted a manuscript to the journal. The main reason is that I've focused more on evolution or psychological/cognitive anthropology journals or AJHB since I've been accepted there repeatedly already. So I'm very excited to announce that my first submission to AJBA was accepted and has been published as a Brief Communication. Here is a link to the article on the journal website, which is the best place to access it to influence the impact factor (have your interest counted). However, it's gonna be behind a paywall eventually, so hit me up if you need access before I eventually post the PDF to my webpage. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.24741 It's gratifying to be contacted for excellent pieces like this new one that came out in The Atlantic last week. Katherine Wu digs into the various studies of tattooing and the immune system, including comments from a phone conversation we had a few months ago.

www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2023/03/tattoo-science-immune-system-effects/673462/  This absurd headline was circulating while we wrote this piece, so we worked it into the article to show how some people apparently think. This absurd headline was circulating while we wrote this piece, so we worked it into the article to show how some people apparently think. My friend Becci Owens, Associate Professor of Psychology at University of Sunderland specializing in evolutionary psychology, had started working on a scoping review of psychological studies of body modification a few years ago but was stalled. I volunteered my lab to help her finish it. It took us about a year to discover that a "scoping review" is a real thing and not another word for a systematic review. After developing a coding system for the corpus of articles Becci had gathered, I googled scoping reviews and found the articles by Nunn like this one that describe scoping reviews in detail and realized that I'd led us all astray for a year. When we refocused on what a scoping review actually is, it became apparent that we simply needed to describe the basic patterns of how psychology studies of tattooing have been conducted. When we started, we noticed that so many of the studies looked for correlations between tattooing and negative personality traits and risk behaviors, despite the fact that most of the same articles and other contemporary sources note that no correlations between tattooing and negative personality traits how been found and that the primary correlations are with openness to experience and youth. So, our secondary objective was to try to understand why so many studies reify tattoo stigma by studying it as though it were a negative behavior and trying to understand causes of such poor behavior. In examining the group of studies that included tattooing as a "stigma" variable in this way (the largest category by far), it became clear that there was a temporal factor. Early studies were looking at penal and mental health populations, seeing lots of tattoos among patients relative to the general population, and trying to determine if marking the self is some aberration of fragile identities. Later studies seemed to indicate that tattooing itself is not a negative behavior but let's just throw it in anyway because we wonder if it might be a useful way to identify people at risk for mental fragility in the general population. But, though I paraphrase, what the hell is that anyway? I have long argued that such studies should just use the Big 5 Personality Inventories because what they're interested in is not risk-taking behavior so much as openness to experience. It appears that by the 2000s, scholars such as Viren Swami had laid to rest with explicit studies saying that all tattooed and non-tattooed people are the same, but even then his titles were ambiguous, leading people to potentially think there are differences if they don't read further (which, shocker, many people don't). Anyway, it became apparent that studies shifted from the above to social psychology studies that look at tattooing in much more interesting ways, such as how tattooing can have different meanings or impacts depending on the type of job you have or how tattooing may intersect with multiple marginalities to influence how people are treated in healthcare settings. These more granular studies are much more interesting. When we looked at the history of the discipline of psychology, the studies we note start after the first renaissance, which was much more recent than generally assumed--tattoos were only out of fashion for about 15-20 years. The pattern of psychology studies also follow the general patterns for research foci in the field of psychology. As of earlier this month, the article entitled "Deviance as an Historical Artifact: A Scoping Review of Psychological Studies of Body Modification" researched and written by Becci, me, Alex Landgraf, Steve Filoromo, and Mike Smetana, has been accepted for publication by Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. Click here to read a preprint of the whole paper. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed