|

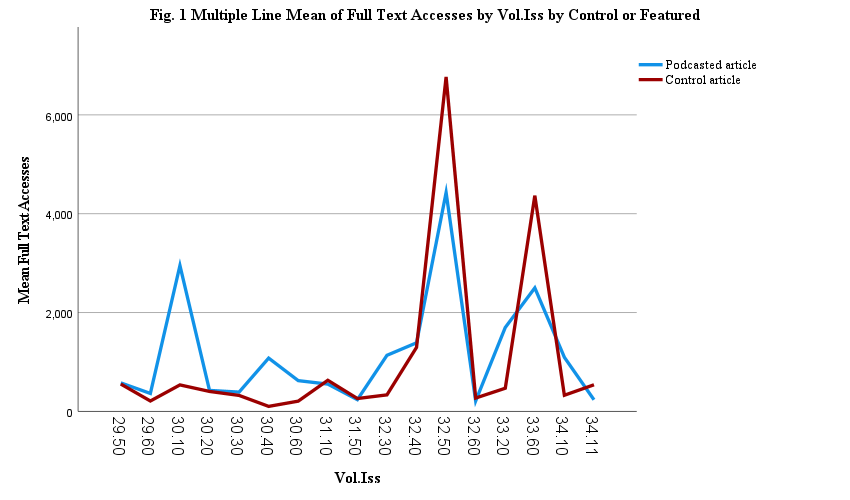

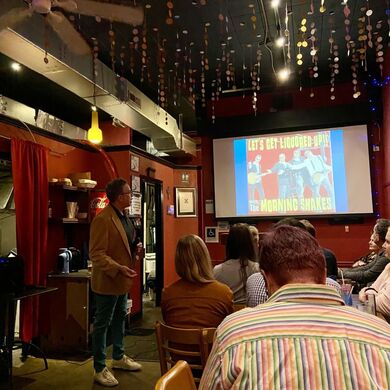

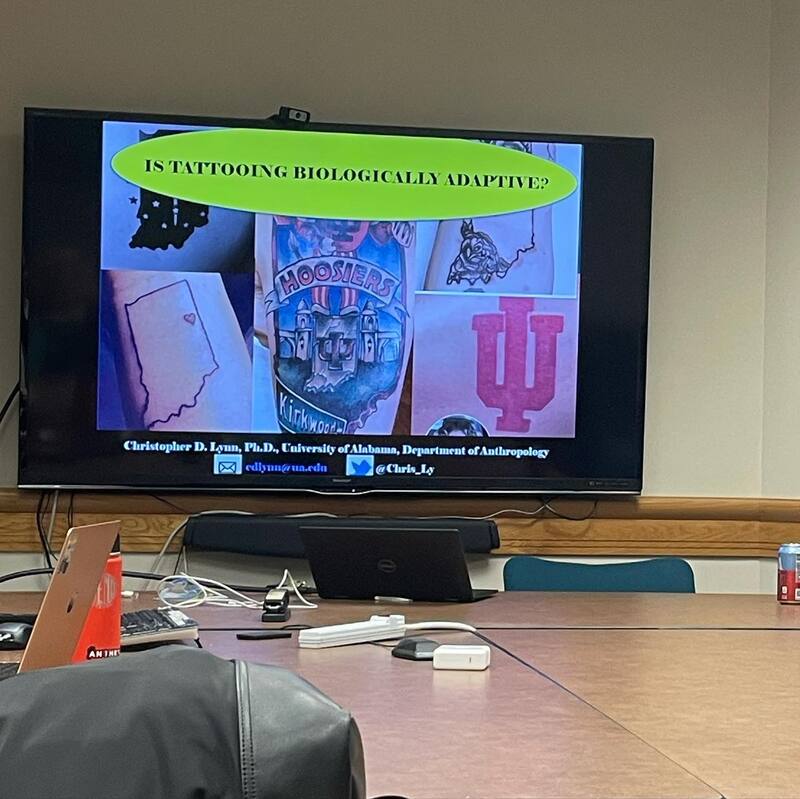

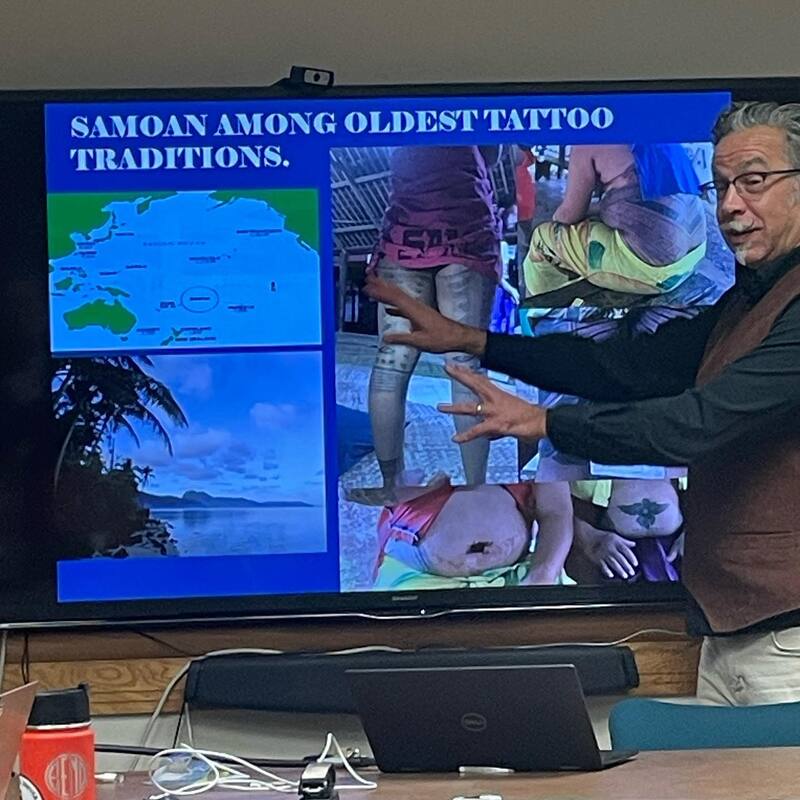

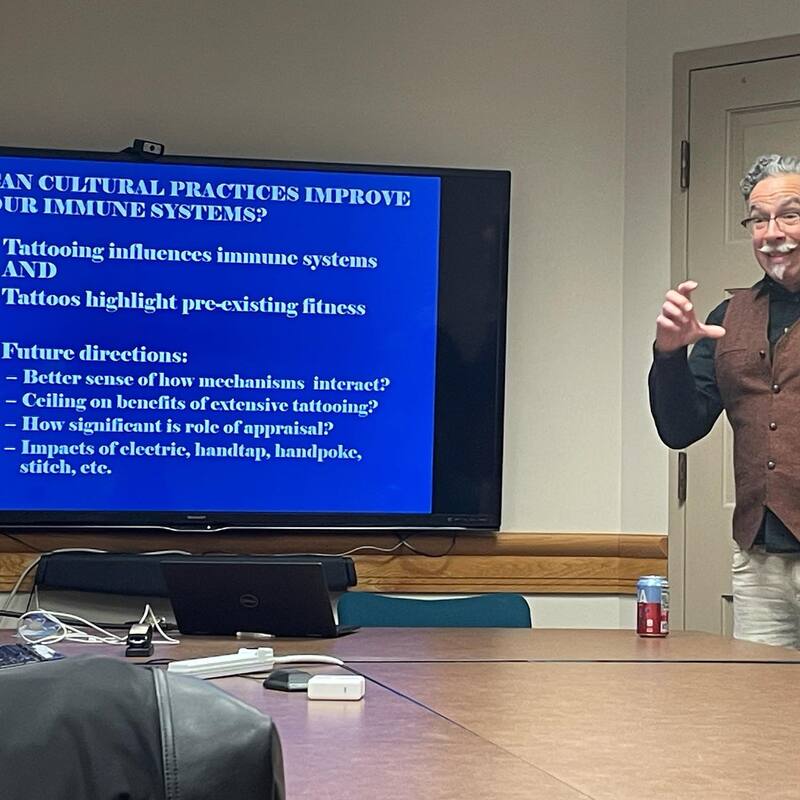

In 2019, I was one of the last cohorts of fellows for the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) Leshner Fellowship for Public Engagement. I thank my friend and colleague Dr. Julie Lesnik for recommending this program to me and me to this program. The program was designed for mid-career professionals and helped me and other fellows take another step up from what we've achieved in our careers and efforts at public engagement. We thought we were ahead of the game, but we learned what more we could do and that publicly engaged scholarship is a discipline and not just something I thought I could do because I can talk to a public audience. The requirements of the Leshner Fellowship were to administer a public engagement project related to our research and another for a scientific institution (usually our own university). I developed a documentary project about tattooing in Samoa and proposed to develop tenure and promotion guidelines at my university for evaluation public engagement.  Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. Dr. Timothy Eatman, me, Dr. Drew Pearl, & Dr. Eatman's daughter, who drove from Atlanta to surprise her father during his visit to the South. In 2021, I received a Provost Faculty Leadership Fellowship from UA to develop the T&P project, and this past year we piloted the Public Engagement Learning Community (PELC). It's been renewed for another year, and the goal of the program is to develop a UA community trained in and supportive of publicly engaged scholarship. A community will support the development of public engagement initiatives and shepherd scholarship, as well as be available to evaluate dossiers containing significant publicly engaged scholarship. This semester has been a pique experience in publicly engaged scholarship for me in a way that I didn't realize until I started writing this. It really started before the spring because the PELC program began last year. In the fall, we invited several scholars to campus for the workshops, but, ultimately, they became Zoom presentations for one reason or another. These included a recorded interview with Dr. Timothy Eatman from Rutgers, a presentation and discussion with journalist John Hammontree, and a presentation by Collette Cann and Eric DeMeulenaer, authors of The Academic Activist. By contrast, all of our presenters this spring were in-person speakers, which I have always found make more of an impression. We had a Zoom presentation by Tricia Allen in January, but in February we had a visit by Dr. Timothy Shaffer from University of Delaware and visits from Drs. Diane Doberneck and Timothy Eatman in March. Hosting these workshops and learning about the field of publicly engaged scholarship influenced how I approached the talks I gave and meetings I've attended throughout the past month. The week after Dr. Eatman's culminating workshop, I went to Florida Gulf State University to give an invited book talk, went to Reno for the annual meetings of the biological anthropology organizations, gave a book talk in Birmingham for a bar audience, and went back to my homeland Indiana to give a series of all of my talks. The lesson for all of the talks I gave throughout April as a publicly engaged scholar is to invite oneself to give talks. When I worked in the music industry, bands didn't get record deals or make any money if they didn't tour and promote themselves and their records. In academia, we put books out via academic publishers and rely on those publishers to get our books into university libraries. In many cases, academic books are neither written for nor available to a general audience. In my own publishing experience, my sole authored book that I've been promoting is print on demand. I think this means there are no copies on hand to ship to stores for any urgent demand because when I have tried to order them for my talks, the books are in no hurry to be shipped. The order takes time to process, then the book takes time to be printed and shipped. I am not a fan of this business model. Publisher support aside, invite yourself to give talks. Say you're in the area of a university because your mother paid to bring you home and gave you access to a family car, offer a free talk to the local departments related to your work. This is the best way to recruit graduate students to your program, to introduce potential buyers to your book, and, most importantly, the best way to open up a philosophy of exchanging lectures/faculty expertise between universities. Dr. Anna Osterholtz and I started doing this between Mississippi State University and the University of Alabama. We no longer have anyone specializing in bioarchaeology or skeletal collections to study, but MSU has an expanding program. Conversely, MSU cannot offer more than an MA, but UA offers multiple MA and PhD tracks in anthropology. Invite yourself to give talks because you have something you want to promote. Send a free copy to friends working at other universities. That's what I did to get a talk at FGSU. I sent copies of my book to Drs. Nate Pipitone and Max Stein. Nate and I were in the same evolutionary psychology lab in graduate school, and Max was a graduate student of mine. I didn't ask for a talk, but I probably said I'm available, and Nate offered me one, so we made it happen and I told him about Max. They didn't know each other before they coordinated my talk but are now colleagues. Furthermore, while I was there, I had a bunch of meetings with Nate and Max and their students and came away with multiple potential research collaborations. Think psychedelics and belongingness.  Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. Flynn Lewellyn and I compared the pageviews of American Journal of Human Biology articles highlighted directly on the Sausage of Science podcast to control articles not highlighted from the same issue. In Reno for the Human Biology Association Annual Scientific Meeting, my undergraduate student Flynn Lewellyn and I presented a poster on publicly engaged scholarship and the Sausage of Science podcast. We left the theory of out the poster, but Flynn and I were determined to tell everyone why our poster is important. I introduced them to Agustin Fuentes and mentioned needing to do something about publicly engaged scholarship in the main forums of our organizations. Agustin is currently battling with millions of trolls on Twitter because of his SciAm post about the non-binariness of sex and non-existence of race, etc. Agustin suggested we do a position paper on this topic, so in my mind, we're now doing a position paper. I put out an informal query about a 2024 session somewhere on publicly engaged anthropology and got a bunch of responses indicating interest, including from the editor of American Anthropologist. And don't just invite yourself for academic talks---find those local Science Cafe or Science on Tap or or whatever they call the "grog talk" program that probably exists in a town near you. They are programs that host academic talks in bar/restaurants. If you can't find one, start one! They are a great way to meet local business owners who share similar values and other academics who like talking with a beer in hand. Last fall I was invited to be one of the initial speakers for the Discourse Birmingham series, hosted at local bars in Birmingham. I gave a tattoo talk in the fall at Monday Night Brewing Company, and it went really well. I felt great about the talk, and the hosts Lawrence and Janek invited me back for another talk this spring at Rojo. This gave me a chance to tweak my book talk for a public audience. I've given public book readings but not yet a public talk on this book, so this was important for me. And, again, I think it went really well; this is based purely on people staying to meet me until the bars closed, and they kicked us out. My mother gave one of my books to her pastor because she thought it would be of interest to her church congregation. The Garden is one of those churches that has a roughly Christian template but is mostly about communing with other humans, having a sense of a Higher Power that loves everyone, and community service. My mom likes that the pastor emphasizes messages that resonate with modern life and keeps services short. The pastor likes the book because it's interesting and, as she pointed out several times, the only academic book that's made her laugh out loud. She and my mother arranged to have me speak this past Sunday as what was in fact the main talk of the service, and my mother paid to bring me up. I talked about fireside relaxation, spiritual transcendence, and the biology of self-soothing. Since the trip was paid for, I'd be able to stay at my parents' place and have access to their vehicle for free, I offered myself up for free lectures to anthropology departments at other nearby universities. I wanted it to be worth the effort for me to travel and my mother to pay for me, so I reached out to people I already know. I've been active in professional organizations since I started graduate school and cohost a weekly science podcast, so, among other reasons, I know a fair amount of people I can reach out to. I got in touch with colleagues at several Indiana universities and managed to book a tattoo talk at Indiana University on Monday and a public engagement talk at Purdue on Tuesday. I went to IU right out of high school for my first two years of college. It wasn't in anthropology, but that was still cool and special for me. I gave a tattoo talk and met another anthropology professor who's been tasked with teaching the "anthropology of sex, drugs, and rock'n'roll." I may have dropped Paul Mahern's name, who I only know personally thru Facebook but whose band was the first punk rock show I ever saw. Mahern is lead singer of The Zero Boys, Indiana's first and best hardcore punk band. He has been a recording engineer, producer, and studio owner for 30 years, and is now also a college educator. I gave a talk about publicly engaged anthropology and how to make it count at Purdue on Tuesday. I offered them one of my usual talks, but I know enough people at Purdue who know enough about me that they asked for a different talk. They asked for a talk about my public engagement, such as my podcast... So I took the opportunity to combine the workshop I've been running with my discipline to give tips specific for an anthropology department with a similar scope to the one I'm in. While there, I met with Kari Guilbault, a bioarchaeology student who has been conducting an MA study of Nubian mummy tattoos. We had communicated before COVID19 and I offered a talk to Purdue if I could ever get to my folks during the academic semester (only an hour from my parents' house, so a low-stress offer). It was useful to workshop this new talk for my friend and primary host Dr. Melanie Beasley. Melanie and I have gotten to know each other through biological anthropology professional organizations over the course of our careers. Their department included me as part of their Anthropologies of Tomorrow series and thanked me for inviting myself, because departments also become too busy too organize their funded speaker series. Colleges and departments provide funding for such series, but departments often forego these opportunities because faculty feel or are over-serviced. As a publicly engaged scholarly, these are the types of opportunities I foster (as host) at my own university and seek out via others' programs. Melanie gave me some good advice on how to flesh out the slides to make my points; and I realized I can integrate more of my projects as examples in ways I hadn't thought of previously. I haven't mentioned making it count. What I mean by that is academics need to justify this publicly engaged work as scholarship to get institutional recognition and protection for it. As my friend and colleague Drew Pearl said this year in probably the more profound statement I heard through our tutelage of the PELC program, "universities are structural institutions and inherently conservative, but the faculty tend to be progressive," or something to that effect. Boom. Mic drop.

But not really. Since they are conservative, we have to meet them halfway by developing ways to measure public engagement and turn it into peer-reviewed scholarship, which is the coin of the realm. The examples I use in this talk include our recent efforts to measure the impact of the podcast and turn the #Hackademics series into a special issue but the many retrofitted articles I've written about public programs I've developed or events I've been involved with. This, I suspect, will be the basis for a position paper...

2 Comments

The Human Biology Association & American Association of Biological Anthropology annual meetings were held at the Peppermill Resort and Spa in Reno, Nevada this year. Technically, I should list the AABA first because they are the primary sponsor and organizer of the conference. However, I am more active in the HBA and attend more HBA functions, so I set it first in my report.

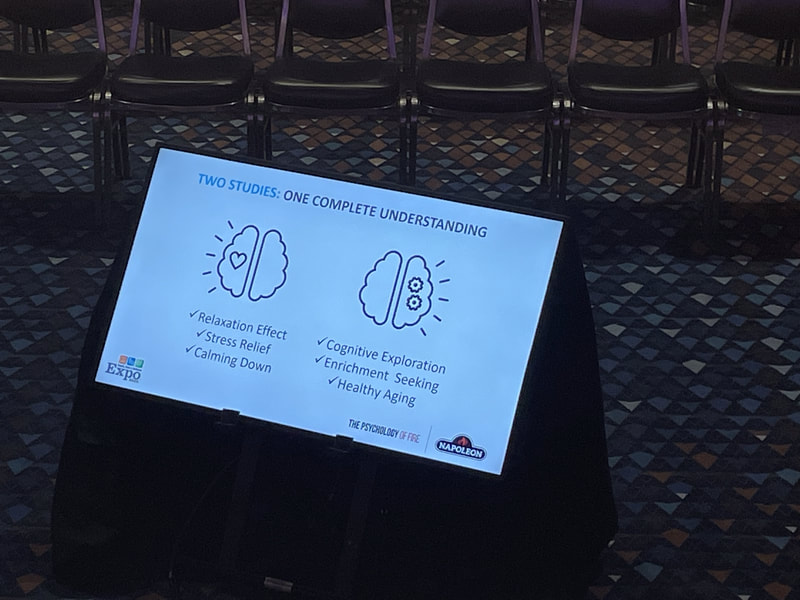

The Peppermill was an interesting choice. I was looking forward to the excitement of being in a resort hotel for nearly a week, but it wasn't really what I expected. People kept joking that it was a Cheesecake Factory on steroids. However, it will have been memorable, and it was a great conference with excellent presentations, interested students, and fun and creative conversations! As a member of the HBA Executive Committee, we had a dinner/meeting the first night to prep for the business meeting, and otherwise I hung out with friends/colleagues Eric Shattuck, Cara Ocobock, and Saige Kelmelis. On Wednesday was the the HBA poster session, plenary, Pearl Memorial Lecture, and HBA Awards Reception. HBERG students Flynn Lewellyn (undergraduate senior) and Lindsey Clark (doctoral student) presented on public engagement via the Sausage of Science Podcast and the Fireside Relaxation Study, respectively. Thursday was sessions, the HBA Business Meeting, and the Student Speednetworking Reception. There was hanging out in a lounge with live Americana music. There was also a brief attempt to warm up in the outdoor heated pool that backfired, then we went to the AABA Reception. Friday were the flashtalks in which I presented as the end of the HBA conference. There were AABA sessions all day, the the AABA Business Meeting and Awards Ceremony. My dear friend and colleague Cara Ocobock won a Leakey Foundation Award for Science Communication at the meeting and gave a lovely speech. I may have gotten choked up. Cara invited me as her +1 to mingle with the AABA Executive Committee and awardees for snacks and beverages. The conference lasted through Saturday, but I left on Saturday, along with many of those I was hanging out with.  One of the things I've learned about working with private industry is that academia doesn't always move fast enough for marketing purposes and that business people don't have any idea how slow science can move. Of course resources can make a big difference, and I am grateful to Napoleon Fireplaces for the support they provided for us to replicate our 2014 study with their electric fireplace. This project has gone faster than our original study, which took 5 years from inception to publication, but it's been a year since Napoleon got us the funds and can't wait to hear what we've been up to. How do we find a happy medium? We make a promo video for the company to send to its annual conference and share where we are now, data were have also now been published as an abstract in the American Journal of Human Biology. Actually, the advertising agency Hoffman York that has Napoleon as an account and recommended highlighting the health benefits of electric fireplaces found and liaise with me. They brought a crew to town and filmed the ad. There are two sides of this that I want to highlight. This is the kind of ad or promo that a student interested in film or communications might do as a project, so it's a great way to inculcate interdisciplinarity in a lab and in training students. It then has a mutual benefit of highlighting the project and work of the student researchers and provides a learning experience for the student doing the film. The idea of doing an ad for the Fireside Relaxation Study came up last year from Hoffman York, but it was actually Journalism & Creative Media major and HBERG member Miriam Anderson who first began such a project and came up with the idea independently. MIriam had been in the process of filming when the semester ended and our schedules changed. I hope to reconnect and finish the piece for both of our sakes in the near future and share the finished product here and our other socials. The other side is that working with private industry means there is funding specifically for marketing and people who can produce such ads quickly, on behalf of the company. This ad is being produced in addition to the funding and fireplace they provided. In both cases, I think it's important to engage the public in various culture ways with scientific findings. I don't make any money from working with Napoleon. The fireplace they donated sits in a small office in my lab, where our experiment takes place. This is applied anthropology and one means of making an impact on our world through our discipline. New doctoral student Lindsey Clark & I were invited speakers for a panel hosted by Napoleon Fireplaces on the Psychology of Fire in Atlanta, GA, March 3-5, 2022.

We have received generous resource and funding support from Napoleon Fireplaces to replicate the 2014 Fireside Relaxation Study with a real, electric fireplace in the coming months. Here we are setting up a fireplace in our lab!

Would Our Early Ancestors Have Watched the Super Bowl?By Christopher D. Lynn “It’s not your fault you watch football all day—man has always been captivated by watching stuff,” states a Coke Zero commercial that aired during the U.S. football season in 2013. The ad shows a person gazing hypnotically at a television, then cuts to an ancestral human staring at a fire. This might seem like just a bit of fun, but as an anthropologist who has studied the impacts of both activities on the human brain, I can attest that it’s true. Gathering around a large-screen TV with family, friends, and food to watch the Super Bowl has, indeed, been predisposed by human evolution. People have sat around campfires relaxing and telling stories for hundreds of thousands of years. A strong case can be made that this has created a selective evolutionary pressure for people who can chill out by a fire, which puts them in the mood and position to learn from storytelling, and to act cooperatively rather than independently. Today’s media devices, from television to smartphones, have harnessed some of the same qualities of campfire experiences that make us feel good, such as the multisensory stimulation and narrative storytelling, thereby concentrating and focusing them into a potentially harmful overdose. With increasing concern about the addictive nature of social media and screen time, it is important to consider just why and how these media are so compelling. Fire is one of the cornerstones of humanity’s long history. Anthropologist Richard Wrangham has suggested that the invention of cooking over a fire led to a step change in our intellectual abilities: Cooking enhanced the amount of energy we could get from food, allowing our ancestors’ brains to become larger. The development of the hearth had social impacts too. Someone had to tend the fires and coordinate the cooking. Wrangham, along with archaeologist John Gowlett and psychologist Matt Rossano, suggests that tending fires and performing rituals around them forced humans to figure out how to plan, cooperate, and possibly even to speak. E.O. Wilson, emeritus professor and museum curator of entomology, compared early human campfires to the nests of ant colonies: a nurturing spot that helped to develop the important social interdependence of human groups. There is limited evidence that early humans came together around fires to process tools and cook, but as cognitive archaeologist Steven Mithen points out, more recent Homo sapiens certainly did. Fireside activities may have provided the spark for many human innovations. There is no direct evidence of humans kindling new fires (creating one from scratch as opposed to tending one), but the oldest technology to make bow drills for starting fire appeared around 125,000 years ago. The social context of modern fire behavior was evident by the Upper Paleolithic, approximately 40,000 years ago, which is also when art, needlepoint, fishing hooks, clothes, and other incontrovertible signs of cultural behavior appear in abundance in the archaeological record. Gathering around an evening fire is also an important opportunity for calm information exchange. During the day, biological rhythms produced by elevated cortisol and other stress hormones keep humans awake and provide the pre-coffee bump needed to be motivated and get things done—like finding and preparing food, and cleaning up around the house and yard. But as cortisol levels drop in the evening, we’re able to sit and relax. We’re in a mood to tell and listen to stories. Anthropologist Polly Wiessner has found evidence for this among contemporary hunter-gatherers: Their daytime conversations are mostly functional, but at night people tend to gather around fires and chat. This is the core venue for retelling a society’s great stories—and passing along information that is central to a group’s future survival. The late evolutionary biologist Richard Alexander suggested that storytelling is vital for human development: Creative endeavors such as novels, comedy acts, and plays provide a type of surrogate scenario building that individuals do not have time or energy for, or simply can’t afford to personally explore. We can’t all learn firsthand which berries are fatal to eat or which animals are the most dangerous; we tell stories, both real and fictional, to share these lessons with others. For these reasons, we are compelled to watch and recount not just romantic comedies or speculative science fiction but also traffic accidents and even war. In 1861, Washingtonians actually took picnic carriage rides to watch the Battle of Bull Run. Today we have soap operas, telenovelas, news, and sports to encapsulate the melodrama of human experience and conflict. And we recall significant events: Alabaman football fans recount Mark Ingram’s classic season that won him the Heisman Trophy for most-outstanding college player, and football fans from Indiana hash over “deflategate,” the accusation that the New England Patriots deflated footballs to earn their win in the 2015 playoffs. We are wired to tell such stories. All of these things—storytelling, cooperative behavior, intelligence, and relaxation—may have coevolved in a complex interrelationship. My students and I have found that the multisensory experiences of fires reduce blood pressure and are most relaxing for those with greater tendencies to be social. People who become calm and mesmerized by the flicker of a campfire might have had an evolutionary advantage over those less susceptible to this relaxation response. The ability to zone out isn’t exclusive to humans: Other animals have the capacity to lose focus and enter a semi-catatonic state. For example, my graduate adviser, psychologist Gordon Gallup Jr., and his research team successfully hypnotized chickens. But humans seem to have harnessed this effect to usefully de-stress or unwind around the campfire. There are other things that have a similarly relaxing effect. People are also naturally inclined to enjoy watching sunsets, lapping ocean waves, and gurgling streams—and now fish tanks, lava lamps, flows of people on city streets, computer screen savers, and television. Our recent follow-up comparisons found that watching TV produces similar blood pressure effects to staring at fire. There is an additional aspect that hammers home the allure of television: Media researchers Byron Reeves and Esther Thorson found that the pans, zooms, and quick cuts used as part of TV storytelling trigger something physiologist Ivan Pavlov termed the “orienting response,” which is essentially a startle response to some unexpected motion or sound. When we discover that those motions or sounds are not dangerous, a mild (and pleasant) endorphin release quiets the stress response. I suspect that watching fire has this effect too: The pops and sparks from a fire provide a mild sense of passing danger that may add to the pleasant campfire experience, though I haven’t studied this from a neurological perspective. Television and other multimedia repeatedly stimulate the orienting response, keeping us rapt and providing a quiescent feeling of being drugged. The effect has become so concentrated that these feelings may actually be addictive. Just as humans have evolved to enjoy the taste of sugars and fats, our modern capabilities and technologies put us in a position to abuse those tendencies. Sugar, a flavorful substance that was once necessary for survival, now gives us obesity. The pleasant relaxation of fireside storytelling now gives us “cyberdependence.” So, when you gather with friends and family around the flickering screen to watch the Super Bowl, just remember: There’s good reason for you to be there. But don’t stay glued to the screen all week. This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here. I tweeted yesterday to David Samson that Asher Rosinger is making me look bad, so all the collaborations that make him so productive. Of course, I'm not really competing with Asher. We just profiled Asher's productivity on a recent Sausage of Science podcast for the Human Biology Association, but it is motivating. https://twitter.com/Chris_Ly/status/1048337483220627456 David and I spoke in 2016 about collaborating on a study of sleep and fire. Truth is, both of these guys have been very productive, and David has already taken the first step in this research direction already. In a paper that came out last year (Hadza sleep biology: evidence for flexible sleep-wake patterns in hunter-gatherers. American Journal of Physical Anthropology), David and his colleagues examined sleep patterns among the Hadza with regard to fire and other factors. They did not find an influence of campfires on sleep patterns, but they make a thoughtful suggestion for our future research. How does fire influence waking cognition? We know smartphones, televisions, and the associated blue light has influences on attention and such. It's time to delve into the light that influenced our brains for most of the last 400,000 years. ![A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]](http://evostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/samson-et-al.jpg) A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com][/caption] A functional linear modeling comparison between the 24-hr sleep-wake pattern of the Hadza and a small scale agricultural society in Madagascar characterized as nocturnally bi-phasic, segmented sleepers. The Madagascar population showed a pronounced increased activity after midnight and a pronounced decrease in activity around noon, whereas the Hadza showed continually increased activity from sleep’s end until noon when activity showed a steady decrease until a prolonged consolidated bout of sleep in early morning. The bottom panel illustrates the point-wise critical value (dotted line) is the proportion of all permutation F values at each time point at the significance level of 0.05. When the observed F-statistic (solid line) is above the dotted line, it is concluded the two groups have significantly different mean circadian activity patterns at those time points [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com][/caption]

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed