|

We have a new article out in Pacific Journal of Health that explores a case study of tatau. We collected cortisol throughout multiple days for a man getting a Samoan pe'a tattoo. This is the first documentation of the physiological response to traditional tattooing that we know of. Read the full open access text here.

0 Comments

Michelle Myles in the Tattoo Museum, July 2024. Michelle Myles in the Tattoo Museum, July 2024. Michelle Myles is a tattoo artist originally from St. Louis but who has been tattooing on New York's Lower East Side since before it became legal again in NYC in 1997. She was the owner of Fun City (I remember Fun City II as the only visible tattoo shop in the Village when it was illegal, run by Jonathan Shaw). Later, she started Daredevil Tattoo with her partner Brad Fink on Ludlow Street, which at the time had a few hole in the wall bars that featured occasional bands, the all-ages punk club ABC NoRio, and heroin dealers. Then they moved down to an even shadier part of LES at Division St. and Canal near the East Broadway stop on the F train, Seward Park, and the old Jewish Daily Forward newspaper building. Today that neighborhood is bougie and much safer, without any obvious heroin dealing going on. I took a tour of the tattoo history of the Bowery with Michelle, and she told me that she tattooed a bunch of the dealers, who then protected her in the neighborhood. Michelle is a registered NYC tour guide, and her husband is a tattoo collector. They have a Tattoo Museum featuring an Edison electric pen, which was modified to become the first electric tattoo machine by Samuel O'Reilly. O'Reilly is originally from England but set up shop in NYC in the early 20th century, and they have one of his machines, as well as hundreds of sheets of flash from celebrated early and mid-twentieth century artists from New York. I arrived late because of time zone issues when booking, but we hit it off, so she squeezed in the full tour. It helps that I used to be a tour guide for the Lower Eastside Tenement Museum, so I already knew the history of the social and architectural histories of the neighborhood and could skip to the tattooing.  Thomas Edison's electric pen was the basis for the invention of the electric tattoo machine. Photographed at the NYC Tattoo Museum. Thomas Edison's electric pen was the basis for the invention of the electric tattoo machine. Photographed at the NYC Tattoo Museum. Michelle and I are the same age, both came from the Midwest to New York around the same time (she came a few years before me), and did our times in the music scene before settling down into history and intellectual pursuits, so we had a grand time talking shop as she took me to the Bowery and showed me where Charlie Wagner had his shop, where Lew the Jew had his shop, where Apache Harry had his shop (also Jewish fyi), and the list goes on. These shops were in the backs of saloons, barber shops, and dentists and only occasionally were stand-alone businesses. She talked a lot about the role of the elevated train over the Bowery making it a dingy place, which I recall from Michael McCabe's book from the 1980s, New York City Tattoo. Tattooing existed in New York and other cities before it became electrified, but it certainly took off as an industry with Edison's and O'Reilly's inventions. As I learned from a recent webinar by Chuck Eldridge of Tattoo Archive, O'Reilly was one of several people tinkering with Edison's patent and simply the first to patent a device of his own. Tattooing has been practiced without electricity for thousands of years, but in the 19th century, numerous inventors were toying with ways to electrify tattooing. The now well-established lore is that after Thomas Edison invented the electric pen to automate filling out forms in triplicate, a number of tinkerers rushed to refine it into a tattoo machine. The first successful patent was given to Samuel O’Reilly.  In Samoan handtap tattooing, the striking of the 'au with the sausau with two hands creates the same activity the electric tattoo gun does. An artists can therefore hold the tattoo machine in one hand and stretch the skin taut with the other hand. Samoan tattooists require what are called stretchers or pullers (toso in Samoan). In Samoan handtap tattooing, the striking of the 'au with the sausau with two hands creates the same activity the electric tattoo gun does. An artists can therefore hold the tattoo machine in one hand and stretch the skin taut with the other hand. Samoan tattooists require what are called stretchers or pullers (toso in Samoan). What is different about the electric tattoo machine? Electric machine tattooing is different simply in the mechanization that speeds up certain aspects of tattooing. The principle of the electric tattoo machine is that something is moving the needle back and forth at a rapid pace. Tattoo machines can be made from anything with a moving part, which is why so many prison tattoo machines are made from such devices as CD players or electric razors. In the electric tradition, the whole machine is held in the artist’s drawing handing and operated with a foot or finger switch. Non-electric styles achieve the same movement by hand. In the Pacific, one hand holds the tattooing comb (an ‘au in Samoan), and the other hand taps the pattern in with a rod (a sausau in Samoan). In Japan tebori tattooing, the pigment is poked in from the end of a wooden or metal stick of various sizes (called sashibo or nomi). With stick and poke, one administers tattoos by hand with a simple needle or tattoo needle bundle (tattoo needles come pre-made and easily obtainable via mail-order) hafted to a pencil or chopstick.  Paul “Junior” Sulu’ape pounds on his thighs to work the feeling back into them. He and his brothers Peter and Ata are sixth generation tufuga tå tatau, and Paul spends anywhere from 6-12 hours a day, six days a week sitting cross-legged on the floor of a fale giving traditional Samoan tatau in the outdoor Cultural Arts Center in downtown Apia on the island of ‘Upolu, Samoa. As a titled master craftsman, Paul’s proper name is Su’a Sulu’ape Paulo III. They are of the Su’a guild of Samoan tattooists, and the Sulu’ape family have inherited the Su’a title through family ties. Paul’s father is pule in charge of titles and land for the family. Those his father has trained in traditional tatau can earn the Sulu’ape title. Those especially trusted can earn the Su’a title. Paul and his brothers earn them automatically through training as tattooists and being sons of Su’a Sulu’ape Petelo Alaiva’a. As most experienced tufuga working today at the Cultural Arts Center, Paul serves a head matai or chief for the samaga ceremony that takes place when tatau are completed. His legs are stretched out under a leaf mat as he massages the stiffness out of his legs, as it is inappropriate to point the soles of bare feet at others. Paul grew up in a tattoo family. His grandfather Paulo I passed before he was born, but his uncle Paulo II, father Alaiva’a, uncle Petelo, uncle Lafaele, and brother Peter were all hand tap tattooists in the Samoan tradition. However, culture is not static. Much as tatau has been uniquely maintained in Samoa through the missionary and colonial periods, accommodations have also been made to modernity. To ensure compliance with global sanitary standards. The ‘au or hammer has been redesigned with material that can be sterilized in an autoclave. Paul’s father Alaiva’a introduced these changes in the 1990s. Paul began tattooing with electric machines and picked up hand tapping from watching his father and brother. He has never used the prior tools made with boar’s tusk, which purportedly felt slightly different to use and were more painful to feel. Paul grew up in the 1980s and 1990s and spent as much time in chairs as his father and grandfather spent sitting cross-legged. While the ~25 hours required to complete a pe’a seems almost intolerably painful, the hours spent leaning over body after body tapping in Samoan designs seems even harder. Paul has dedicated himself to preserving his family and cultural heritage but needs acupuncture even as a young man in his twenties for the pain and discomfort of its hardships. I began working with the Sulu’apes to study the biology and culture of Samoan tatau but was surprised by such additional aspects of cultural embodiment. Tattooing is the perfect topic for anthropological study, given the discipline’s varied foci on culture, biology, linguistics, and archaeology. We also have a brand new chapter on the medical anthropology of tattooing in the Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification. This was co-authored with former graduate student Michael Smetana. Mike wrote the first draft for a course, and I slogged away on the rest of it over the course of a year or two. Marco Samadelli wrote a short summary and didn't have time to write a full chapter, so they asked me to combine his chapter with ours. I'm quite pleased with it, though I've already found a few things that will need to be fixed if they retain it for future editions. Check it out here.

Our lab has new publications! The first is an article about podcasting, written by me with Courtney Manthey and Cara Ocobock. We compared listens to episodes of the Sausage of Science podcast that were highlighted on the pod to those that weren't from the same issues and, save for COVID outliers that were accessed at extraordinarily high rates, podcasted articles were significantly more likely to be accessed. This is good news for academic podcasters! Check it out while it's open access: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajhb.24105

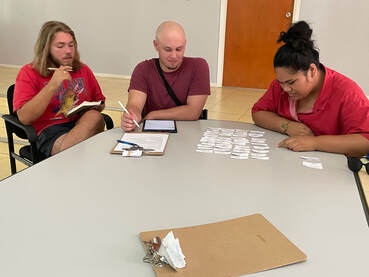

Thursday, July 20, 2023 Leota sees us onto the ferry to American Samoa. Leota sees us onto the ferry to American Samoa. The scheduled time to go to the ferry for the overnight ferry to American Samoa was something like 6pm. I was originally going to drive there and leave our rental in the parking lot. Leota didn't feel comfortable leaving us to our own devices nor with us leaving our car in the lot, so he volunteered to drive us there and keep watch over our car at his house. He didn't think we needed to be there at 5, as I suggested, to ensure we weren't late. He said we could be there at 8pm and be fine. He didn't think the ferry would leave before 10 or 11pm. I was naïve, and Leota would turn out to have been optimistic. When we told people we were taking the ferry to American Samoa, we got a variety of reactions. Some were impressed by our mettle; ours warned us of the weather and conditions. Many Samoans have never taken the ferry to American Samoa. I think it is a bit of a status thing to take the flight over the ferry, but it is also a time and comfort thing. The financial savings are not worth the trouble, and we would've paid more to avoid it if we could have. he wait for the ferry while they loaded took several hours in a crush of humanity. No one seemed to know how the loading worked, so everyone kind of crowded in, us included. We crowded near the front until someone finally told us how to read our ticket, and we realized we would be loading among the last groups, so we got out of the way and sat down. Families were stocking up on food for the trip, buying meals from vendors at the station. We should have done the same. At any rate, we finally boarded around 8:30 or 9. We initially thought we'd have to sit on the floor of the cafeteria, but we ultimately found seats. Josh had been worried about getting seasick and purchased Dramamine from a pharmacy in Apia. We took the meds and slumped in our seats. Grant went wandering. I think I woke up before we even left and eventually got down on the floor with everyone else to try to sleep. The storm kicked up before we left and buffeted us all the way there. The boat continually went up and slammed down, up and slam down. It was jarring and relentless, but I never felt unsafe inside the cabin. The boat never tipped side-to-side. Just the steady up and SLAM. I thought the only entrance to our cabin was the one on the far side of the room, as people kept climbing over sleepers throughout the night to reach it. But it turned out there was another door right behind us that just wasn't being used, except by Grant, who found it eventually during his wanderings. Josh and I didn't leave the cabin we were in, trying to stay settled, not vomit, and get some sleep. I did in fact sleep on the floor most of night, nodding in and out of consciousness. Most of what I know that went on comes from Grant and Josh. People were laying over every available floor space, so I had no compunction about sticking out into the aisle. My main memory is of being stepped over repeatedly throughout the night. I heard the coughing, but I didn't realize it was seasick vomiting. Apparently, a guy behind us was just throwing up on the floor in front of him as he lay trying to sleep. Grant spent the night wandering the ship and surfing the storm up top with a bunch of Samoan guys he befriended. He was sopping wet when he finally came down. Because Samoa is now at the beginning of the day and American Samoa at the end, the trip lasted about 6 hours, and we landed the morning of the day we'd left. Very confusing. I am time-zone challenged under the best of circumstances--this was breaking my brain a bit. I had made reservations for us at Sadie's By the Seashore, one of two decent hotels in American Samoa. I tried to book the Tradewinds, the other decent hotel, which is near the Olaga offices in American Samoa, but they were booked up. Sadie's had vacancies, and was right next to the ferry terminal, so we were set.  Here we are at Sadie's getting a meal & multiple Cokes with ice. Stupid. You'll be paying for that ice for a few days, dummy. Here we are at Sadie's getting a meal & multiple Cokes with ice. Stupid. You'll be paying for that ice for a few days, dummy. When we walked out, I looked around and thought I knew where we were. We'd go to the right, and Sadie's should be right there. We walked for about 15 minutes, and I said, "wouldn't it be funny if we walked the wrong direction?" We had a running joke of some sort, so we kept walking, but after another 15 minutes, I questioned my own impeccable sense of direction and asked a guy coming out of a store. He pointed the direction we were walking, so we thanked him and kept walking. After nearly an hour, we reached the tuna canneries, which I knew were well beyond our destination. I flagged down a cab, who gave us a ride to Sadie's for $10. It was all the way back around Pago Pago Harbor from where we'd come, just a few steps to the left of the ferry. He was a retired Filipino-Samoan schoolteacher, born and raised in Samoa. I didn't have the bandwidth to chat, but Josh and Grant kept up the banter for us. Grant was fading however. We got ourselves checked into Sadie's early and crashed out in our room. We'd tried to reach our families back home to let them know we were safe, after ominously texting "taking the ferry in a storm" before an extended radio silence. However, we were too fried to move immediately and crashed out in our room for a few hours. Then we got up, had some food, drank some Cokes over ice that would later give us serious traveler diarrhea, and sent out emails to try to make arrangements for Friday. I reached out to Joe Ioane from Off Da Rock Tattoos, who was our main collaborator and data collection site back in 2017. I'd had to leave a week early that summer due to a family emergency and did not say goodbye properly. I also got in touch with Joshua Naseri, who runs the Olaga programs in American Samoa and made arrangements to meet for a happy hour beer or three tomorrow. Friday, July 21 Riding around Nu'uuli & Tafuna in the back of a pickup. Riding around Nu'uuli & Tafuna in the back of a pickup. We were at lunch in the restaurant at Sadie's when I see someone familiar. I keep looking and keep looking. I finally decide that it's Leuila Ioane, Joe's wife, and the person with his back to us therefore is probably Joe. I'd told him in my message that we were staying at Sadie's, and he'd responded, so if he was here, wouldn't he look us up? Apparently not. I finally went up to them, and indeed it was. Joe and Uila are a powerhouse couple. They're both Army Reserve, fitness buffs, and driven entrepreneurs. When we were there in 2017, Joe was building a workshop attached to the tattoo studio for Off Da Rock Fashions, Uila's business. She designed cloths, and they had a team of seamstresses making them. I have two great handpainted ties. Joe and Uila and their kids (four now, two more since last time) all look like rock stars modeling her designs. Anyway, I ask Joe if he can recommend a rental agency, as I'd decided we really did need a car and was about to go try to rent one. Instead, Joe offered to rent me one of his extra cars for a flat rate if I could drive manual. I definitely prefer island cars from friends when I can get them. Cuts right through the bullshit, and I trust Joe. Unfortunately, neither Josh nor Grant had any experience with stick shifts, so I would end up doing all the driving. After lunch, we jumped into the back of Joe's truck and accompanied him on errands until he got back to his neighborhood in Ottoville. He hooked us up with the car, and I gave Josh and Grant a brief tour of Leone until we realized Grant was flagging. So we went back to Sadie's. Grant took a nap, and Josh and I went to meet Joshua Naseri in the restaurant. We had a few beers with Josh and told him about our project in person. I'd been emailing back and forth, but this was the first time we got to meet in person, and the project is much easier to explain in person. Furthermore, he was really intrigued by the methods. His team would be able to try out data collection over the weekend, then we'd debrief on Monday and go from there. We were thrilled. The Olaga team were locals, so they'd be able to collect data much more easily than we could. One of the adjustments that we'd all agree should be made it that we'd pay more in American Samoa. I don't think I've mentioned the payment, but it was made very clear at the beginning of our data collection that anything but cash would be seen as colonial and paternalistic. In Samoa, we were paying $25 tala per participant for pile sorts, which seemed like a reasonable amount to our collaborators and participants. Given the exchange rate, that would be around $9.33 USD, which is both a ridiculous amount and too low for participant reimbursement. We ended up paying $25 USD in American Samoa because it felt equivalent to people, even though it wasn't and everyone acknowledged it. Weird. Time to convalesce and watch Women's World Cup Soccer, which was being played in New Zealand and Australia, so near our current time zone. Josh and I are sports fans and looked forward to having something to watch when we weren't out and about. Grant was still sleeping and would be down and out for most of the next two days with a fever. I was paying for that ice non-stop all day. Good times. Tuesday, July 18, 2023 University of Alabama researchers Josh Lockhart and Grant Pethel administering pile sort activity at National University of Samoa. University of Alabama researchers Josh Lockhart and Grant Pethel administering pile sort activity at National University of Samoa. Josh Lockhart, Grant Pethel, and I went down to the shipping terminal to buy ferry tickets for American Samoa. We were planning to travel to Tutuila to collect data. Tutuila is American Samoa's main island, the Manu'a Islands the other. I had planned to go to Ta'u in the Manu'a Islands of American Samoa as well, but it was impossible. Flights among the islands are touch and go. The second airport in Samoa just reopened in July, so more flights had become available. However, the bottleneck of people traveling back and forth to see family was such that they were booked up for several weeks. The only way to travel to American Samoa during the six weeks of the field season without having known ahead of time was to travel by ferry. This would be rather difficult because our return flights to the US were out of Samoa. Had I planned better, we'd have flown into Samoa and out of American Samoa and saved ourselves considerable stress. We had gone directly to the ferry the day before after getting back from Savai'i, but Josh did not have his passport with him so we were not able to make the purchase. We planned to come right back with the passport but were tired and by the time we got back and didn't want to drive back downtown. We would have bought the wrong tickets if we'd done that because of the time zone issues. We would have to buy a ticket that would leave on Friday from Apia at around 8pm and arrive in American Samoa on Friday around 2am. The return ferry would leave American Samoa around noon, and that would get up back in Apia on Saturday around 2am. It's very confusing to me. We'd chatted with our host, Lai, and he'd told us which tickets we needed to buy. So we did that and then went to the CSS offices to conduct some pile sorts of participants we had recruited. For lunch we went to Burger Bill's. We thought it was funny and kept accidentally ending up in their parking lot for some reason and had a hankering for a burger or something and went there. Bad idea. I have not been a fan of much restaurant fare in Samoa, but this was gross. I got a mushroom swiss burger for some reason. I should have known better because my first job was at Hardee's, and Hardee's had a mushroom swiss burger that I found gross then when I liked fast food (working at Hardee's soured me on that place forever). Burger Bill's burger was similar, so I left it unfinished. Grant and Josh had underwhelming experiences as well. Wednesday, July 19 Left tray: pulasami, oka, fish is coconut milk; right tray: chicken, pork, yams, seaweed, cucumber-tuna, and bread? Left tray: pulasami, oka, fish is coconut milk; right tray: chicken, pork, yams, seaweed, cucumber-tuna, and bread? The best food we have eaten in Samoa has been what people have served us at their homes, for the most part. I'm not a fan of the curries I've had there. They are simply flour based sauces, I think. Fortunately, we were eating at Leota's for dinner, which would include the #2 pig. He also promised to make a couple versions of Oka (fish in coconut milk and lime juice), which is one of my favorite Samoan dishes. In the meantime, we ran errands and tried to meet up with Su'a Alaiva'a Sulu'ape. We'd been popping in, and Ata finally gave me his cell number and told me to call him. I did but just got voicemail. I also texted. We had arrangements to meet that day but could not nail the time down. Su'a will often roll in a few hours after the arranged time, but he is Su'a, so no one says a word. However, we were on a schedule, so we could wait an hour or so but then would have to jet. We sat watching Junior, and he introduced us to the family he was working on. It was the son/nephew of the Nu'uuli fautasi team in American Samoa. I told Josh and Grant how important these guys are, and they were very friendly and receptive. They live in Pago Pago, so we made arrangements to meet up with them the following week for data collection when they'd be back home and we'd be over there. We went over to Leota's around dinnertime and met his family. This included his wife, young daughter, and baby son. His wife is a teacher a Samoa College. They also live with Leota's brother and three cousins, who go to university and help with the kids. Basically, all land is family land, and they are from Savai'i. So when they are in Savai'i, they obviously have places to stay as any kid would going home. But when they are in Apia, this is an extension of their village, giving them a family to stay with in Apia too. Leota tells me that from now on, I will stay with them and in the village when I am in Savai'i. Leota's mother bought the property they have in Apia, and she is buried there. This was a big deal for Leota and a decision he is unsure was the best political move for him. He aspires to be High Chief some day, and he certainly has the character and aptitude for it in all the best ways. His mother was an important chief, and she should have been buried on the traditional family land, rather than a new piece of property on another island. However, Leota was so close to his mother that he could not bear to be separated from her, so he pleaded with the High Chief to be allowed to bury here in Apia. In previous years, I've puzzled about the Samoan custom of burying family in the front yard. This year we got a thorough education about it from Leota. According to Leota, fa'alavelave are more important than the Christian holidays, even though Samoans are very Christian. Fa'alavelave are gift-giving celebrations that accompany important village events, such as weddings and funerals. Funerals are as lavish as weddings for Samoans, with family flying in from all over the world. The celebration of the deceased lasts several days and includes lots of event planning. We witnessed one next door from our Air'B'n'B that lasted several days. They had multiple Taula party tents set up and were outside cooking in the traditional style near the edge of property near us. There were ceremonies we caught glimpses of in the distance, and there were crowds of people.  Research teach with Leota's family in Apia. Research teach with Leota's family in Apia. Like weddings, professional photographers capture it all on film, and Leota showed us the video of him wailing atop his mother's coffin. Fa'alavelave are important and expensive, but Samoans don't think of money as something that needs to be squirreled away for personal use. They are a communal-oriented culture, especially compared with my own midwestern US background. In Samoa, everything is owned by the family and village, not individuals, so money flows through the family and village and is not kept by individuals. For the most part. Banks accommodate this; fa'alavelave loans are easy to get, have no/low interest, and you can get multiple fa'alavelave loans even if you haven't paid off previous ones, because of the value these events have in the culture. Burying family in the front yard is very important in Samoa. By doing that, family remain close. They are buried in the front out of respect, and the size and design of their monument often indicates their status in life. Untitled people may have unmarked graves in the yard but are still with family. In Savai'i, Leota pointed out several graves around the monuments that we had thought were simply landscape decor. The cemeteries I've photographed in previous posts are often graves of displaced, foreigners, or those whose family land is gone. There is one such near NUS. Leota regaled us with these stories, and he and his family served us dinner and entertained us with some ukulele playing and singing. I will have to ask him to teach me a Samoan song next time, as I usually travel with a small stringed instrument to pluck on (uke or stick dulcimer). He family is lovely and daughter is charming, and the food was fantastic. Leota's oka is spot on, and even though there was too much food, I ate two servings of oka. Leota explained to us that their tradition of hospitality requires that they serve guests and make sure they are satisfied and retired because they eat. He told us this in Savai'i, which is why he was always sitting before us as we ate and never eating himself. So again, he sat before us and talked with us while his wife and cousins brought us food. By this point, Leota felt comfortable giving us friendly cultural advice on how to behave, which we appreciated. He had told us going to Savai'i that humility is the thing. Josh and I would like be seen as flashy because of our hair. Josh has long hair, and I put product in mine and have a somewhat extravagant mustache. Grant had his head shaved, which is seen as simple. So he reinforced that I should be sitting in the middle as the important person. They would bring us a tray of food and extra of everything as soon as we tried to finish a dish. It was a Sisyphean effort to finish a meal because they would refill everything so fast. Fortunately, we had learned from Dionne the trick of at least having a bite of everything and not feeling guilty beyond that. Like money, food flows through the village. It is not wasted if it is not all eaten. It will go to the untitled people serving us later, and what they don't want goes to the pigs or the dogs, and it will replenish itself.  Grant, Leota, me, and Josh outside the RSA, Western Samoa. Grant, Leota, me, and Josh outside the RSA, Western Samoa. We managed to not be completely distended by the end of the meal because Leota wanted to take us out for some beers before we left for American Samoa. So after the obligatory photo of everyone, we went down to the famous RSA. I say famous because apparently it is known as one of the best nightclubs in the South Pacific. I thought this was odd, as there are a lot of clubs popping up around Samoa and American Samoa it seems. However, it turns out this was one of the first, and it is one of the few places a touring band might play if they went to the South Pacific (which I think is probably rare, expect among islanders musicians themselves). Grant is very good at putting himself out there to get the party started. He jumped out on the dance floor and had local women dancing with him. We had a great time with Leota and learned a couple other lessons. He thought it was weird that each of us paid for ourselves going in, and I covered him so didn't notice; but the custom in Samoa is that the first person in a group walking in pays for everyone. And when someone gets a beer, they get one for everyone. I actually had been covering Josh and Grant for most things on our National Science Foundation Grant, but they don't cover nightclubs and drinking, so I'd toggled to the American style of covering ourselves. Having friends there willing to tell us these things has been great. I'm very torn about staying with Leota's family in the future, not because I'm not thrilled by the offer and opportunity. I have an excellent relationship with our hosts Lai and Renon, and I learn a lot from them too. Lai and Leota are both talking chiefs, so they are very knowledgeable about Samoan culture and history.  Grant gets parties started and keeps them going. Grant gets parties started and keeps them going. Leota showed us the genealogy of his family he has memorized and written out. As a talking chief, it is his responsibility to know the family history and names. The titles are passed around to indicate status and lineage in the hierarchy. For instance, the title Leota is an important one in Gataivai and widely used. Several of the chiefs we interviewed were also called by their chief name Leota. I promised not to publish it, but Leota let me take a photo of the genealogy. Leota says he has memorized 72 generations but has not completed his memorizing. He knows ancestors that predate the colonial encounter, however, making me wonder about the validity of the concept of prehistory/history with regard to Samoa. Leota says that Samoans know more about their culture than has ever been written down because it is palagi who write things. Samoans live them. But he is worried that his children will lose access to the truth of their culture through learning to read if the truth isn't written by Samoans for the children to read. Matai are responsible for preserving their culture, so he considers this his mission as a scholar. He says the chiefs don't really value the university education, but they appreciate that it must be done to protect them, and they support Leota in this role. The woman who had been dancing with all of us but especially Grant was a US Customs Officer and was trying to get Grant to continue the party with her friends, but he politely declined and we dropped Leota off and went "home." Monday, July 17, 2023 My gifts from the untitled men of Gataivai. My gifts from the untitled men of Gataivai. On Monday we got up and prepared to leave to catch our ferry. The High Chief asked us to stay for the leaving ceremony or if we could come back for the final ceremony before leaving. It's a ceremony presented by the untitled women, as the 'ava ceremony had been hosted by the untitled men. We had exchanged gifts with the untitled men on Friday. We strolled around the area a bit. I was following pigs around because they reminded me of my chihuahuas! I think I found the #4s, and I decided not to get any closer.  Full breakfast and full lunch together! Full breakfast and full lunch together! Since our ferry ticket was technically for 2pm, the village considered us under their care until we left the island, even though we'd have to leave the village a few hours early to get lined up for the ferry and because we wanted to go to the market beforehand. That meant they wanted/needed to feed us breakfast and lunch, so they brought it to us together. Breakfast was awesome. I was still a little overfull from the day before, so koko aris (cocoa rice), fruit, eggs, and bread were fine. But then they brought "lunch," which included hot tuna and cucumber. After the hot tuna last night, I couldn't do it again. Nope. We had so much food from the 'umu the night before that we had a whole cooked #2 pig and a chicken to take back to 'Upolu. We agreed that Leota would take it back to his house, and we'd all go over there for a Samoan meal before we left for American Samoa later in the week. We took photos with the family before leaving, then stopped to see another star mound on the way to the ferry. This was the most visible mound we'd seen yet. This mound had been cleared off in conjunction with the Centre for Samoan Studies (CSS), and the owner had been advertising it for tourism. But they'd taken the sign down and were no longer maintaining the site, using it as a plantation for taro, coconut, and cattle instead. But Leota stopped by the home of the owner and received permission for us to visit with Leota. Not only was this mound the most visible, the low walls or walkways that CSS archaeologist Greg Jackmond had told us about were clear. They were the most obvious route to the mound, so you are walking on them before you realize what it is and that it's a human-made feature you're walking on.

Sunday, July 16, 2023 Grant Pethel, Josh Lockhart, and I watch Leota prepping food for the 'umu. Photo by Tala Esekielu Lealamanu'a. Grant Pethel, Josh Lockhart, and I watch Leota prepping food for the 'umu. Photo by Tala Esekielu Lealamanu'a. When Grant, Josh, and I woke up in the fale tele at 8 am, we were surprised that we'd managed to sleep so late. We were ushered to a shed in the back where Leota and his family were preparing the 'umu. They'd been up since 6am and had already butchered a #2 pig in preparation. 'Umu is food cooked in an earth or stone oven. It's generally prepared on Sunday for after church. The untitled men prepare the feast to be ready when the family returns. Our 'umu would contain pig, taro, yams, and octopus. It was raining outside, and we could see the neighbors up cooking as well. They had a spigot out back for water and cooked in rigged cookware suspended over a fire in the rain. We at least had a roof for our cooking. Leota had purchased an octopus in the market when he arrived from 'Upolu ahead of us Friday. He was about to prep the octopus when we wandered up. Leota's cousin Kalama seared the octopus on the fire to firm the flesh and make it easier to cut. Leota first cut the tentacles off, then squeezed the ink from the head into a bowl of coconut milk. He cut the entire octopus and all the tentacles into bite sized chunks and put it in the ink coconut milk mixture. Leota then filled taro leaves with octopus and the juice while Kalama held the giant leaf like a bowl, then wrapped it up in foil to seal it. They made probably a dozen of these. Next they prepared the #2 pig. Samoans rate the pigs 1-4 by size. Fours are the biggest and are reserved for fa'alavelave or very special occasions. The pig's viscera had been previously removed. Kalama used a coconut rib folded in half to make tongs and picked up a hot stone from the fire and crammed it inside the pig. He then stuffed a bunch of wet leaves in the fill the remainder of space, but we were told that we do not eat those leaves. I am guessing they either help maintain the moisture inside or they simply keep the stone from falling out. The taro and yams had already been prepared and were in baskets around us. Kalama and his wife Tala pulled the wood off and out of the rocks with help from their son and a young cousin. They then spread the rocks out a square sheet of metal, exposing as many red hot coals as possible. They placed the pig directly on top of the coals, then piled all the taro, yams, and packets of octopus. They covered all of this with fresh taro leaves, then dry taro leaves, then several old mats, and finally an old blanket. This would all cook in about 45 minutes!  Clockwise from left: Saimin, fish, taro, pulasami (taro leaves in coconut milk), pork and chicken, octopus. Clockwise from left: Saimin, fish, taro, pulasami (taro leaves in coconut milk), pork and chicken, octopus. While the food cooked we conducted some pile sorts. Then we got dressed to dine with matai. Several families from the village had also contributed to the 'umu meal with the chiefs. We had three #2 pigs, including the one we'd watched being prepared, 4-5 chickens, and twice as many fish. There was also the yams, taro, and octopus! It was all delicious and super filling. I particularly enjoyed the octopus. We ate with the chiefs, exchanged greetings and took photos, and then several of them stayed to be interviewed and administered the pile-sort activity. After the pile sort, we received a special gift from the High Chief. He had had his family made a special sweet taro dish that takes over 24 hours to prepare and is a treat (I think it was fa'ausi). We were grateful, though we were extraordinarily full from the 'umu.  Leota conducts pile sort while Josh and Grant take notes. Leota conducts pile sort while Josh and Grant take notes. We went to the High Chief's house in the evening to conduct more pile-sorts among his family. It was Sunday, and I wondered how much Christian piety the Samoans would show toward drinking in Savai'i on Sunday. They'd apparently appreciated the beer we'd brought and drank with them on Friday, and we'd had more with them on Saturday night. The High Chief was drinking a Taula when we arrived, so that answered one question. Then he broke out a bottle of red wine to share with us, which answered the other question. I wasn't really looking to drink while we were collecting data, but I accepted a glass. However, my stomach was full as hell from all the food, and the wine did not sit well with me. They wanted to feed us too, and even though we were full from the 'umu, they brought us grilled tuna sandwiches. I nibbled down half a sandwich. As Josh conducted a pile-sort with one of the High Chief's family, I felt the nausea creep up on me, and I started breathing deeply to prevent losing it. I started sweating, and my eyes glazed over as I tried to get a grip. Grant noticed these signs, so when I popped up and stepped into the darkness for a minute, he knew why. The High Chief asked where I was going, and Grant told him I just need to get a little air. As I stood off behind a car in the dark, I lost the wine, after which my stomach felt better. I stepped back over and continued the interviews without anyone else the wiser. After data collection, we went back to the fale tele and settled down for the night. I can't recall if it was Saturday or Sunday night, but we got a big storm one of those nights. The wind blew so hard that rain came into the fale tele sideways. I was far enough from the edge that I pulled the sheet over my head and kept sleeping. Leota and Kalama got up in the middle of the night and put up tarps to keep the rain out. Leota thought we were cold because of the sheet over our heads and brought us more sheets. Leota got a photo of me looking like a mummy under the sheets, but he never did send it to me. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed