|

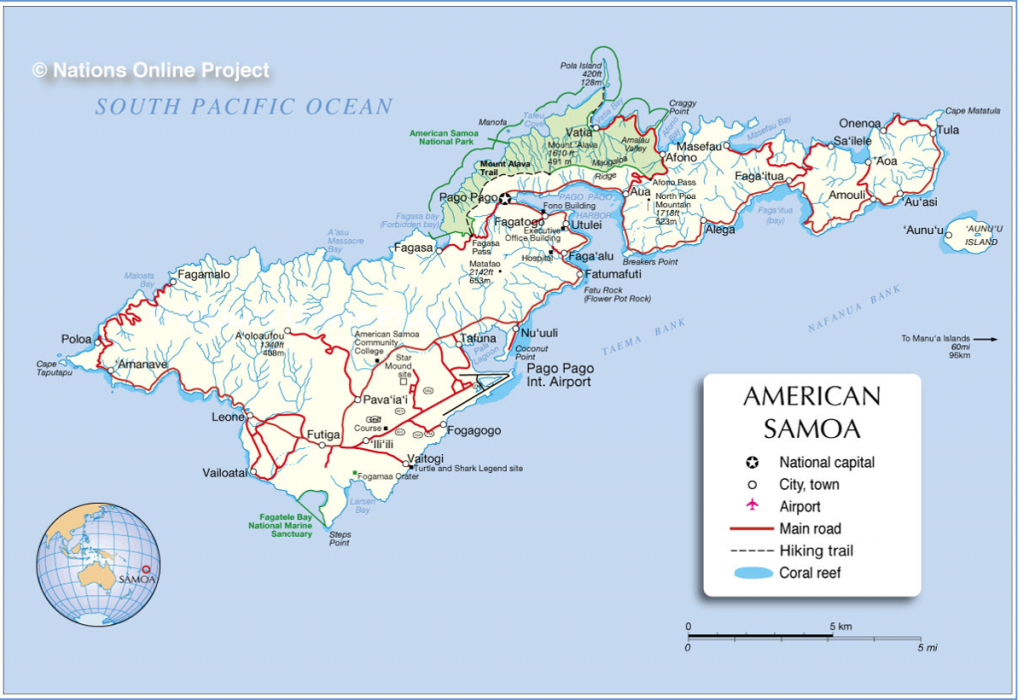

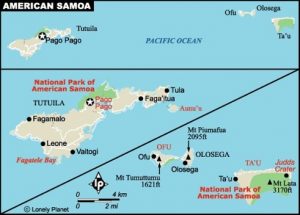

Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We were scheduled to start data collection with Chilo and the malu at 11AM in Pago Pago, with Joe at Off Da Rock in Nu’uuli at 1PM, and with Su’a Wilson in Leone at 3PM. In theory, we could have been stretched much further. The island is not that big, and there is only one road, but the speed limit is only 25 mph, and we’d have been truly screwed to have collecting even two sets of data if they were at complete opposite ends of the island. As it was, we never went past Pago Pago or Leone this trip, but it would take at least 30 minutes to make this trip, so we needed to time things right. Things would inevitably change. And they did. First, we called Chilo to confirm the time of the malu and got no answer. Chilo had given his wife’s number on Monday when his battery had been dying, and I had kept it, so I called her. I asked if he was available, and she said, no, he is at work. At work? Isn’t he supposed to be starting a malu. So we drove to Family Mart, and I looked for but could not find him. I asked the clerk at the register, and she said he was butchering meat. I wandered around till I found him, butcher’s apron on, putting cuts of fish in the store freezers for sale. He greeted me and told me that the malu was delayed until 1PM. He did not get my calls because reception was poor in the freezers. I asked how he would get there, and he said he would either take an aiga bus (what they call the rickety private buses used for public transportation) or the family would get him on their way to his house from Leone. The whole family of the girl getting the malu, of course, would be accompanying her and, in fact, had arranged things with him. First, I thought to volunteer to pick him up and drive him, but then I knew this might make coordinating the other two tattoos difficult, so I promised to call him at 12:30 to make arrangements. I left somewhat aggravated but accustomed to such changes and delays. Off Da Rock was delayed as well, though not as much. Joe was building a shop for his wife in the house next door and was frequently running around picking up materials before an appointment. When he arrived for an appointment, he would still need to go back and forth to manage workers in the house while also tattooing and managing his business. He is the only tattooist in his shop and managing many affairs. He and his wife also run a morning workout for the community that starts at 5AM every morning, are officers with the National Guard, are financial advisers, and design and sell clothes on the internet and out of his shop until hers is finished. Plus they have two young daughters and, like all good Samoans, attend church regularly and are active members of their villages. Joe handles all the fa’alavelave obligations for his family rather than send to his parents in the mainland for remittances. Fa’alavelave are the obligations that interfere with normal life and call for special activities or celebrations, such as funerals, weddings, granting of matai titles, births, birthdays, and so on. Joe’s uncle a few homes over is the village high chief. We had collected enough data at Off Da Rock that we were able to get the first sample and anthropometrics from Joe’s client, then drive to Pago Pago to meet Chilo. We had to leave Joe and the client with the post-test saliva collection tube and instructions on how to collect the saliva. Apparently, we neglected to tell them how to take the collection straw off the tube and screw the cap on, as we recovered the sample the next day lying on its side, wrapped in a paper towel, with some of the sample dribbling out. There was enough still in the tube to use, but the devil of data collection, like so much, is in the details. We drove to Pago Pago, and I had to drop Michaela off with materials for collecting demographic info and saliva, along with good cameras we had borrowed from the American Samoa Historic Preservation Office. A malu would take more than one day, so we planned for me to take the hand dynamometer and bioimpedance analyzer to collect data at Su’a Wilson’s tap-tap session and collect body density and handgrip strength from Chilo's client later today when I returned for the balance of the session or tomorrow when we returned for the inevitable second session. I drove to Leone and asked Michaela to text me when she got picked up and their session started. The session in Leone started almost immediately. I barely had time to get set up and collect anthropometric data. Su’a’s stretcher, his son Mark, had them ready to go. I sat behind Su’a’s wife Reggie and watched as she fanned everyone, comforted the client, and chatted with everyone. The hours went by, no text. Finally, “still waiting.” That was both a relief and distressing. Su’a took 2 ½-3 hours to complete a tauvae or band around a girl’s ankle. It was her first tattoo, and her mother, who had grown up in American Samoa, had brought her to get it as part of her heritage. As I drove back to Pago, I texted Michaela. She was still waiting for Chilo but had tracked down his wife and was sitting with her. When I arrived, Michaela and Chilo's wife and their baby were sitting at the picnic table where we had talked to him and where I had left Michaela waiting 4 hours earlier. There was a half-eaten package of Tim Tams. I introduced myself then Michaela asked me to give them a few more minutes to talk alone. I wandered around for about 30 minutes until Chilo's wife left. Then Michaela told me to drive to a nearby Japanese place for dinner. Chilo was not doing a malu today after all, but he had another tattoo job and would be calling us. Does anyone at this point believe that he will be calling us or that he will doing any sort of tattoo? Neither did we, but we did eat nearby, if only to be able to process what was going on and get some food in us. After several hours of calling Chilo and having him say he was on the way, Michaela called his wife. The Samoan islands are very traditional and very gender stratified. One of Michaela’s cardinal rules of research there is that she will not form friendships with males. It is too fraught with gender disparities and opens everyone up to accusations of impropriety. If she must work with a male in some capacity, she goes to lengths to get to know the wife as well. So Michaela called Chilo's wife to forge a relationship, since she was allegedly going to be working in Chilo's studio without his wife present. Michaela’s instincts in this regard have been as accurate as her sense that she should bring a male researcher on—me—to be able to talk with high chiefs and other males in her primary research, the impacts of social inequalities on unwed mothers and their babies. American Samoa and Samoa still retain their traditional, male-dominated, village-based political structures for the most part and to varying degrees. They share the same culture and language but, for the past 100 years, slightly different colonial histories. In the early 19th century, missionaries took firm root on all the Samoan islands. It was just before and during this period that several paramount of high chiefs sought to extend their power over multiple islands, using European trade goods acquired by converting to Christianity toward these ends. It was through these political and economic pursuits that Samoan and colonial interests became entwined. It was the son of the first successful missionary who established copra as a trade item, which is dried coconut from which oil can be extracted. Flourishing copra plantations were established across the islands, especially the bigger and more agriculturally accessible Upolu. A German trading company moved in and monopolized this industry and was so successful that when the business failed in Europe, the German government bailed it out to retain the income coming from Samoa. However, German treatment of natives was poor and exploitative, and, in an effort to retain control of their own lands, chiefs in Tutuila sought protection from the U.S. government against German incursion by offering sole use of its prized deep sea harbor at Pago Pago. The U.S. resisted for some time but ultimately became embroiled in Samoan affairs and recognized the need to prevent German colonial expansion throughout the Pacific. A naval standoff between U.S., German, and British ships that nearly came to head was prevented by a sudden hurricane that scuttled nearly all the ships at anchor and killed hundreds of men, forcing a quick negotiation that resulted in the Germans holding Western Samoa and the U.S. Eastern Samoa, later named American Samoa. Western ended up in the hands of New Zealand after World War I, and then became independent in 1962. It changed its name from Western to Samoa in 1997, much to the consternation of American Samoans. American Samoa was managed by the U.S. Navy beginning in 1901. After several failed efforts to install kings of Samoa during the earlier colonial trade period, the U.S. opted to follow the German governing style of allowing Samoans to govern themselves at the village level as they have always done, through a hierarchy of selected matai and a government-selected mayor or pulenu’u. A gathering of representative chiefs or the fono met regularly to discuss issues with the governor, who for the first 50 years as a U.S. territory was a U.S. Navy officer, then an appointed U.S. politician sent to American Samoa, then, beginning in 1978, a native Samoan elected by Samoans.

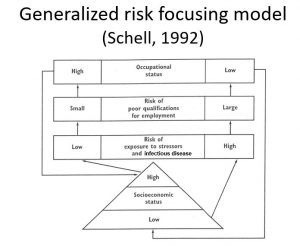

Most people in the U.S. are likely unfamiliar with American Samoa and even the most educated would struggle to find it on a map. American Samoa is the southernmost U.S. territory and is closer to New Zealand and Australia than it is to the U.S. Its strategic purpose relative to, say, Hawai’i has always been limited and, thus, it is in many ways unsullied by modernization. On the other hand, American Samoa is as sullied a territory as there is in other ways. American Samoans having the ignominious distinction of being among the most obese peoples in the world. Samoans have been studied to death by scientists because of their interesting Polynesian ancestry and large phenotype. Aside from the high rate of obesity, Polynesians in general and Samoans in particular are a large-bodied people. Samoans are much sought after as American football players and New Zealand rugby players. Yet because of modernization and a switch, especially in the less agricultural islands of American Samoa, to reliance on trade and, more to the point, U.S. subsidies and aid, American Samoans have transitioned to diets of commodity foods high in calories and low in nutrients and suffer high rates of the diseases of civilization, including obesity, as well as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease. When we dig down a little deeper then, we come back around to John Enright’s noir depiction of the American Samoa Michaela invited me to help study last summer. When a society is highly patriarchal, highly Christianized, and is almost completely reliant on U.S. aid, NGOs, and family remittances, what social group is at the bottom of society suffering the most? Poor women, women with little family support, women with little family support and no husbands, women with children and little family support and no husbands. Of course, this is a synergistic type of situation, one created by the structure of the society as it has developed. Poor women are women without titles in their family. They have no access to village-level resources unless chiefs allot it to them. There are so many political and ritual obligations to become titled and among titled families that resources do not generally circulate much beyond them. Except when a fa’alavelave is held, and there are a lot of them. For each fa’alavelave, chiefs might demand that everyone in the community contribute, especially the family at the center of the celebration. So if a low-rank woman and man want to get married, their families are expected to pay lots toward the celebration. Of course they are also paying, like everyone, toward everyone’s celebrations, so it will take them a long time to have enough money to be able to get married. In the meantime—whoops—they have a baby. American Samoa has the worst condom education of any tribe, territory, or state in the U.S. Sex education is verboten because of their strong, conservative Christian identity and values. Which is a double-edged sword, since this young woman is now pregnant. So she gets in trouble with her village and her church and is literally ostracized from both. This is how she becomes the lowest echelon of society with the most suffering. Often, to save the family from shame, the woman will be taken to Samoa or the U.S. mainland to have her baby, which is then raised by a family member. Secrets are kept. Shame is hidden.

Which brings us back to Chilo's wife. She was mystified as to why he had told us he was doing a malu. He had never done a malu before. He didn’t do hand tap tattoos. He hadn’t done any tattooing in months. He worked so many hours a week at the Family Mart, he could not afford to take off the two days he told us he’d taken off to do the tattooing. He hadn’t told her anything of his plans to meet with us that day and never told her about his extracurricular activities, though he had told her of meeting with us previously and of our interest in his tattooing. He did seem to do tattoos occasionally, but they did not bring in much money and he needed to put in as many hours at Family Mart and ensure his job there. They were barely hanging on. She’d had two children by another man before him, a man now in prison. She couldn’t afford food for those children, so she tried to breastfeed them both and suffered maternal depletion syndrome. She liked how it made her so skinny and attractive, but it was not enough food for the children. They were starving, and her family told her she should take them to an aunt who could care for them. She used to visit them there more, but her aunt chastised them for showing the kids too much affection, as if she wanted them back. She had to pretend she was not their mother, so the aunt would continue to care for them. And now she and Chilo had this child to care for. She did not know why he had told us his studio was right across the way from Pago Plaza. He did not have a studio that she knew of, and they lived far up the mountain off the road. He called a few times throughout this conversation. No, the malu was not happening today. But another person had made an appointment with him. Stay there. He would be tattooing later tonight. We could come to the studio and see that tattoo, take photos. We had explained the entire study to him in words we thought he understand, had given him copies of the consent forms in English and Samoan. We had asked him if he understood and he’d said yes. But to his wife he said he didn’t know we wanted to collect saliva samples. He wanted us to take photos. He thought we were taking photos. He thought we were writing articles and would bring attention to his business. His wife explained to him and said his English was not all that good. She was not sure how much he could read or understand.

This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa.

0 Comments

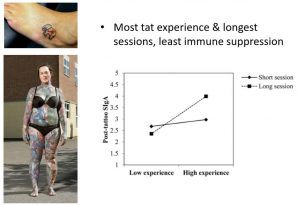

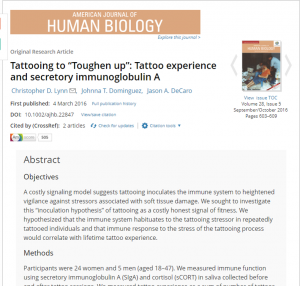

Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We had worried when the study started that we would have difficulty juggling multiple tattoo sessions with only two researchers because we only took along one bioimpedance analyzer (BIA). The study protocol is ultimately rather simple. It involves a short questionnaire about tattoo experience and some basic demographic information, then we collect hand-grip strength using a hand dynamometer, body density using a BIA, and a saliva sample right before the tattoo starts, noting the time, and another as soon as the tattoo concludes. From the saliva samples, we extract immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Immunoglobulin A is an antibody that lines the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract and is a frontline defense against common infections like colds and flus. Cortisol is a stress hormone that increases when the body or mind are responding to a stressor, like getting a tattoo. Part of the classic stress response involves turning off non-essential functions to deal with the source of the stress until the body can return to homeostasis, and the production of IgA is one of the things usually suppressed during stress response. But as we point out as part of our induction protocol, the body can become habituated to certain types of stressors and have mediated responses. Take exercise, for instance, which stresses the body and results in immunosuppression when a person is new to it. With regular exercise, the body actually becomes healthier and is better able to deal with the stress of it, as well as daily potential insults of other types. Unless one overdoes it. Studies of elite athletes find they catch upper respiratory tract infections more often than most and suggest it is due to fatiguing this system. There is a growing body of research that finds overtaxed stress response systems result in deterioration in the body, including cognitive deficits results from apoptosis in the hippocampus. We collect body density as an indicator of fitness and handgrip strength as indicator of underlying neurocompetence. By controlling for these—essentially equalizing people for these variables—we can compare tattoo experience to the changes in cortisol and IgA from the beginning to the end of the tattoo. In our previous research, we found that people with little to no tattoo experience responded to being tattooed with the predicted spike in cortisol and immunosuppression of IgA but that people with lots of tattoo experience did not have immunosuppression. In American Samoa, the logistic catch was that we had one dynanomometer and one BIA between us. Ironically, for much of the study, because there are so few tattooists in American Samoa, there were two of us hanging out for the entirety of a tattoo session when only one of us was necessary, and not even for the whole session. We really only needed to be there for the beginning and end, except for the need and want to collect ethnographic data. As it happened, the same day Chilo said he was doing a malu was the day Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoos had a client and Su’a Wilson was doing the first hand tap tattoo we’d been invited to collect data at. Finally, we had the luxury problem of having come all the way to American Samoa to collect as much tattoo data as we could in 6 weeks and had to juggle three at once. But why did we come to American Samoa? If there are so few tattooists, why not conduct this retest back in the mainland U.S., where there are more tattoo studios in any given town than there are McDonald’s and Starbucks combined (American Samoa doesn’t even have Starbucks, though they do have Starstruck—however, they have two McDonald’s, one of which has been the highest grossing McDonald’s in the world several years running). We came to American Samoa to retest the model because you can’t generalize a scientific finding from 29 mostly women in Alabama to much of anyone else, despite the elementary nature of the finding (this finding, though compelling to media, is consistent with basic stress response and allostasis theory but cooler when applied to culture and especially to tattooing). And we came because the Samoan Islands have the longest continuous history of tattooing.

The myth of the twin sisters who brought tattooing to Samoa is a story everyone knows, though there are different versions of the story. The most common version is known because of “The Samoan Tattoo Song,” which one can hear regularly on Samoan radio. https://youtu.be/wIgCNQeZYBA

As the song indicates, women brought the tattoo tools because tattooing was originally the realm of females, but they made some mistake and ended up switching things around. The longer myth deals with the families who were given the tools, which relates to the guilds that are allowed to teach and apply hand tapping now. Ausage also believes the story originally referred to Fiti, not Fiji, which is short for the village of Fitiuta, but that it has been distorted and confused with time. When the first explorers recorded to have sited Samoa landed, they thought the Samoans wore silk knickers because of their pe’a, which are the male tattoos extending from midriff to below the knees. To be continued… This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity.  Full sleeve by Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoo.[/caption] Full sleeve by Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoo.[/caption]

Michaela and I were despondent from cancellations and because we were collecting data on day two of multiple sleeves (a full arm tattoo) at one studio. Meaning, we were collecting additional saliva samples from individuals we’d already got them from because they were getting big tats that took multiple sessions, so we were collecting pre- and post-tattoo data from day two and didn’t have anyone else we could collect new data from. We hadn’t really worked out what to do with additional data like that. In my previous study, I’d averaged additional samples in and found the additional data didn’t make much difference. We were likely wasting our time, in other words. So I volunteered to drive to the village of Ottoville, out past the Cost U Less, and pick up a family in town for a family reunion who wanted to get their afakasi son (half-Samoan—a distinction I make because Samoans make it, though it both does and does not seem to matter) tattooed and that needed a ride to get there. On the way, I stopped at the Family Mart to find this supposed Tongan.  Cargo boxes at shipping yard of Fagatago, American Samoa.[/caption] Cargo boxes at shipping yard of Fagatago, American Samoa.[/caption]

He supposedly worked in the cargo boxes, which are the shipping boxes that goods come in. Every Chinese and Korean grocer has them lined up in front of their stores. I’m not really sure why. Do they simply have stuff dropped off in them and trade them out, keeping them there for additional storage? I’ve never thought to ask. I also didn’t know people worked in them. But I stopped at Family Mart, didn’t see anyone around the boxes or any doors to knock on, walked around inside first, didn’t see any likely candidates, then went back outside to the car and saw a guy who could have been my Tongan coming out of the box. He had hair clipped short, looked Polynesian possibly but not necessarily Samoan (wasn’t big enough), and his arms were covered with tattoos (though not Samoan tattoos). He was coming out of one of the boxes carrying goods to restock shelves inside. [gallery ids="6419,6420,6421"] He had a dour appearance when I approached him. I asked if he was Tomesi or Ollie (names changed for confidentiality) and he said no. I asked him if he knew Tomesi or Ollie, and he shook his head no. I told him I am a researcher studying tattooing and referenced an article in the Samoa News and radio and TV interviews we had just done about our research to give my story credibility. So far, everyone we had encountered had heard or read one of these, because there are limited media outlets on island. Puzzled, I asked him if he was a tattoo artist, and he said yes. So I gave him my phone number, got his name and phone number, and asked if I could call him to talk to him about our study. He said yes, we arranged a time, and I left to finish my errand, elated by my success in the face of our flagging sampling. I had found the Tongan tattoo artist Niko had told me about, but his name was Chilo, not Ollie or Tomesi, and he had no Polynesian tattoos that I could see. However, even the tattoo experts often have tattoos they’ve collected elsewhere in their youths. I saw so many eagles, for instance. Granted, an eagle is on the American Samoa flag carrying a Samoan war club and fly-whisk, but there are no eagles in American Samoa. It represents the U.S. And Pago Pago. Though this is no different than U.S. teams being represented by Tigers. Fagaitua are the Vikings, for instance. I had promised to call Chilo at a time that evening. The idea that one show up on time to a meeting is a Euroamerican convention or what you do for work and church, not necessarily other situations. So I had the best of intentions of calling him later, but we were spent after our day of resampling the same person and decided to treat ourselves and our foul moods to a movie and dinner out with our friend David to cheer ourselves up. I didn’t notice until the next day that I’d received a phone call during dinner from an unknown number. Now in the mainland, I’m so phone phobic, I’d never call someone back who called me that I didn’t know and who didn’t leave a message, but people can’t leave messages on my cheap American Samoa Telecommunications Authority flip-phone, and who would be calling me? Only someone interested in or related to the research. So I called back, and it was this guy I met in the cargo box. That never happens. Chilo actually called me. We couldn’t believe it. So I arranged for us to meet with him in Pago after he got off work Monday, where he would take us to his house to talk and so we could find it for collecting tattoo data later.  David Herdrich is more than just a friend; he is Director of American Samoa Historic Preservation Office and one of the most important people on our American Samoa research team. David Herdrich is more than just a friend; he is Director of American Samoa Historic Preservation Office and one of the most important people on our American Samoa research team.

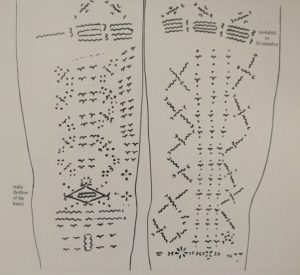

And here we were, sitting anxiously in our car, wondering if Chilo were some type of Tongan criminal, a killer preying on stupid palagi scientists who’d taken no safeguards. Since this is a true story that I am writing for an anthropology class and to describe fieldwork—and lest I reify any stereotypes, I’ll hazard a few spoilers—he was neither Tongan, I don’t think, nor, to my knowledge, had he any malevolent intent. This was all our imaginations, but stay tuned, because it was still weird. We finally voiced our mutual discomfort at sitting in an isolated parking lot behind a building in the dark in Pago and moved the car to a spot in front on the main road. There we sat a while longer. We called Chilo to check on his progress, and he told us he was on the way, almost there. Half an hour later, we called him again, and he was just leaving work...I finally gave him 15 minutes before I was going to leave. When 15 minutes was up, Michaela told me I should call him to tell we were leaving, but I just wanted to bail. Reluctantly, I did call him, and he asked where we were, saying he was in the parking lot and couldn’t find us. This freaked me out. How did he get by? I didn’t want him coming to get in the car or to come to the car window, so I got out to find him. He had come through from the back, and I met him back at the gate, out of Michaela’s sight. But he was nowhere as threatening in person as he had become in my mind’s eye, so I brought him over to the car to introduce to her. Fortunately, he also no longer wanted us to go to his house. Their pastor and his family were there, he said. It might seem odd that a church event was going on at his house, and he was in a dark parking lot with us talking tattoo, but it makes perfect sense in Samoa. We sat at a picnic table in the back of the plaza to talk. This was in a well-lighted area, and as we sat there, some Coast Guard palagis we knew happened by in their uniforms and chatted with us, which gave us additional relief. The story Chilo told us was exciting and incredible. He wasn’t Tongan at all, as I mentioned, but from Western Samoa. He had his own tattoo studio and business on the side, doing tattoos with electric gun and hand tap. He said he had been trained by a Sulu’ape. We explained our project in the slow manner that we do, because English is not the first language of many Samoans, using simple words, repeating certain things, focusing on the cultural elements, ensuring him that we were looking for partners in this study, not simply participants. We shared a copy of the informed consent, which outlined the study in simple terms, in English and Samoan. At one point, Chilo started crying, which was both surprising and touching. He said God had sent us to help him and his business, and he was grateful and happy to participate. The Samoan Islands are 99% Christian. The missionaries did their work well there. Though sometimes being Christian is a means to a social end, the structure of Christianity mapped well onto the village-based authoritarian structure that included top-down morality, and it flourished there. American Samoa is emblematic of anthropologist Rich Sosis’ “3Bs” model of religious commitment signaling. You can observe religious commitment via behavior, badges, and bans. People go to church all the time, wear elaborate clothing, and observe a hefty load of religious taboos. But conspicuously missing among these Bs, Sosis notes, is belief. It’s not necessary to demonstrate commitment, though it often develops simply by following through other three signs, as a way to minimize cognitive dissonance. Many Samoans are cynical about religion, but they are still Christian. I don’t know Chilo's religious values, but his statement that God had sent us to him came as no surprise. What did surprise us is that he said he would be doing a malu this week. It was like we’d bought the Willy Wonka chocolate bar with the golden ticket. A malu is the female counterpart to the pe’a. These are the special midriff and thigh tattoos that only Samoans are supposed to get and symbolize one’s commitment to village, matai (chief), and aiga (family). Malu means to hold together, and the symbols that characterize the malu include crosshatches, like the ties that bind the house together. They represent the importance of the Samoan woman in binding the family and village together. But tattooing is primarily a male domain, so, though we had seen several men getting pe’a, which has similar significance, we had yet to see a woman getting a malu. And Chilo wanted us to part of this tattoo experience. He would have us wear gloves and a gown and be in the inner circle of the tattooing with his stretchers. And he wanted us to take photos. The family would be OK with it, he assured us, and we would not be in the way because the family would be in the room outside. All of this was very exciting but also quite odd. First, all the tattoo artists on Tutuila know each other, as it is a small place. For that matter, most of the tattoo artists in the entire South Pacific seem to know each other, and no one knew this guy. Second, when we asked about hand tap artists, all the same names came up, regardless of who we talked to. Becoming a hand tap artist is no small thing, as it requires an intensive apprenticeship, and there are a limited number of people with whom one can apprentice, especially in the Samoas. If one is a Su’a and/or a Sulu’ape, one is known because one has started as a stretcher for years and been conferred a title with the tools and permission to tattoo. Sulu’ape is the family name and title granted by that family of master tattooists for completing a certain degree of apprenticeship, and Su’a is a higher title. According to historian Telei’ai Fanaea Christian Ausage, author of Laei a Samoa, a book about Samoan tattooing, Sasu’a is one of the ancient tattooing guilds and once associated with a specific family. The title is now roughly passed down by or within families, with whom the Sulu’ape family are associated. There is some tension and controversy now about the legitimacy of Sulu’ape as a family name versus a title and what it means and the linkage of the Sulu’ape to the Su’a guild, but as outsiders, these appear to be largely political and economic distinctions. The Sulu’apes have clearly cornered the market on hand tapping, and someone in their family has trained absolutely everyone else conducting hand tapping who is working today. We met Peter Sulu’ape in Honolulu and Paul Sulu’ape in Samoa and interviewed Chris Ausage about the hand tap artists working today. No one mentioned Chilo, we couldn’t find his Facebook page, even though he wrote down the title of it for us, and he didn’t seem connected to any of these tattoo networks. Furthermore, the idea that Chilo would be a trained Su’a and have his studio set up to keep family out seemed anathema to our experiences of the tap tap tatau experience in the open air fale (or house). At Soul Signature Tattoo in Honolulu, the Polynesian tattoo shop where we met Su’a Peter Sulu’ape, there were several Samoans who had come from Georgia, North Carolina, and Alaska to get pe’a, malu, and other tattoos. Su’a Peter and Sulu’ape Aisea Toetu’u conducted hand tapping in a back room, away from their standard U.S. tattoo parlor set up; but whereas families and friends sat at a distance in the waiting area while tattooing occurred up front, consistent with parlors around the country, family and friends were welcome and encouraged to gather round the person getting tattooed in the back, provided they wore an ie lavalava (the Samoan version of a sarong, worn regularly by females and males and expected in ritual and formal settings). And despite the distance, there were a few family members who seemed to have traveled just to be there while their family members received the pe’a and malu. In Samoa and American Samoa, family participates as skin stretchers at the tattooing in the fale of the Samoa Cultural Center, where we met Paul Sulu’ape and saw him working. Su’a Wilson Fitaou’s sons worked as stretchers in his fale or when he travels to the homes of others for the hand tapping we saw in American Samoa. Family and friends gather around, hold the hands of the person being tattooing, console and fan them, and massage their muscles to prevent stiffness or break up the bruising caused by the hammering of the tap tap. In no case were family kept separate from those being tattooed in our experiences to that point. To be continued... This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. PrologueInstead of syllabus day, I read this story on the first day of my Fall 2017 Neuroanthropology class then launched right into the class. I’d never done this before, but I like to think of the course as interdisciplinary and experimental and that different ways of experiencing materials is important. I was inspired to do this by anthropologist Katie Hinde, who wrote a story to start her human evolution course at Arizona State and blogged about it. Katie is a friend and colleague of mine. She is a contemporary but probably a few years younger than me. Nonetheless, she is trailblazer and someone I admire and look to for inspiration in how to conduct an anthropological career-life. You can find her work at MammalsSuck...Milk, a clever play on words, as her research focus is about mammal milk. This piece is about the fieldwork I’ve conducted the past two summers. I just wrote it the weekend before the first day of class, so, for better or worse, students heard an early draft of this story that may get published on its own somewhere or in a book some day in some form that will probably ultimately be very different than this. I wrote it because I think our work this summer epitomizes the nature of neuroanthropology as essentially biocultural, and because I think this story encapsulates much of our experience of fieldwork this summer. There may be less neuro than you’d expect here, given the course I read it to, but it’s the ethnographic prelude before we’ve finished collecting and analyzing the neuro data.

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed