|

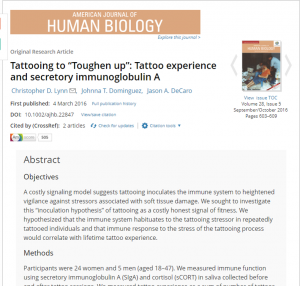

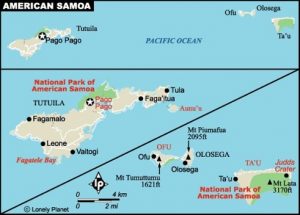

Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. PrologueInstead of syllabus day, I read this story on the first day of my Fall 2017 Neuroanthropology class then launched right into the class. I’d never done this before, but I like to think of the course as interdisciplinary and experimental and that different ways of experiencing materials is important. I was inspired to do this by anthropologist Katie Hinde, who wrote a story to start her human evolution course at Arizona State and blogged about it. Katie is a friend and colleague of mine. She is a contemporary but probably a few years younger than me. Nonetheless, she is trailblazer and someone I admire and look to for inspiration in how to conduct an anthropological career-life. You can find her work at MammalsSuck...Milk, a clever play on words, as her research focus is about mammal milk. This piece is about the fieldwork I’ve conducted the past two summers. I just wrote it the weekend before the first day of class, so, for better or worse, students heard an early draft of this story that may get published on its own somewhere or in a book some day in some form that will probably ultimately be very different than this. I wrote it because I think our work this summer epitomizes the nature of neuroanthropology as essentially biocultural, and because I think this story encapsulates much of our experience of fieldwork this summer. There may be less neuro than you’d expect here, given the course I read it to, but it’s the ethnographic prelude before we’ve finished collecting and analyzing the neuro data.

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed