|

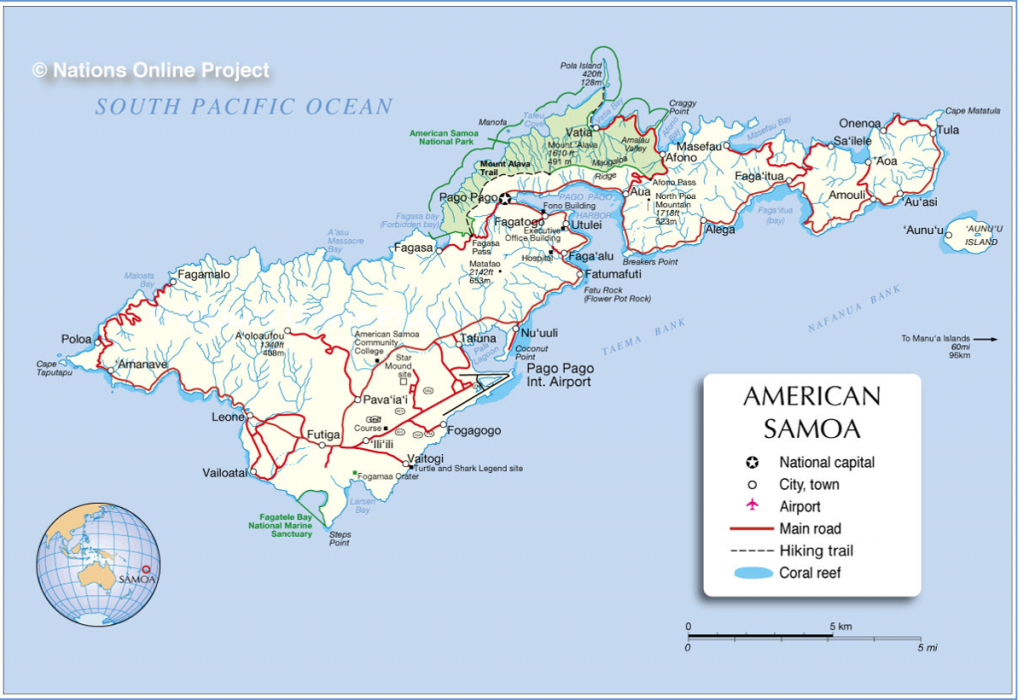

Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We were scheduled to start data collection with Chilo and the malu at 11AM in Pago Pago, with Joe at Off Da Rock in Nu’uuli at 1PM, and with Su’a Wilson in Leone at 3PM. In theory, we could have been stretched much further. The island is not that big, and there is only one road, but the speed limit is only 25 mph, and we’d have been truly screwed to have collecting even two sets of data if they were at complete opposite ends of the island. As it was, we never went past Pago Pago or Leone this trip, but it would take at least 30 minutes to make this trip, so we needed to time things right. Things would inevitably change. And they did. First, we called Chilo to confirm the time of the malu and got no answer. Chilo had given his wife’s number on Monday when his battery had been dying, and I had kept it, so I called her. I asked if he was available, and she said, no, he is at work. At work? Isn’t he supposed to be starting a malu. So we drove to Family Mart, and I looked for but could not find him. I asked the clerk at the register, and she said he was butchering meat. I wandered around till I found him, butcher’s apron on, putting cuts of fish in the store freezers for sale. He greeted me and told me that the malu was delayed until 1PM. He did not get my calls because reception was poor in the freezers. I asked how he would get there, and he said he would either take an aiga bus (what they call the rickety private buses used for public transportation) or the family would get him on their way to his house from Leone. The whole family of the girl getting the malu, of course, would be accompanying her and, in fact, had arranged things with him. First, I thought to volunteer to pick him up and drive him, but then I knew this might make coordinating the other two tattoos difficult, so I promised to call him at 12:30 to make arrangements. I left somewhat aggravated but accustomed to such changes and delays. Off Da Rock was delayed as well, though not as much. Joe was building a shop for his wife in the house next door and was frequently running around picking up materials before an appointment. When he arrived for an appointment, he would still need to go back and forth to manage workers in the house while also tattooing and managing his business. He is the only tattooist in his shop and managing many affairs. He and his wife also run a morning workout for the community that starts at 5AM every morning, are officers with the National Guard, are financial advisers, and design and sell clothes on the internet and out of his shop until hers is finished. Plus they have two young daughters and, like all good Samoans, attend church regularly and are active members of their villages. Joe handles all the fa’alavelave obligations for his family rather than send to his parents in the mainland for remittances. Fa’alavelave are the obligations that interfere with normal life and call for special activities or celebrations, such as funerals, weddings, granting of matai titles, births, birthdays, and so on. Joe’s uncle a few homes over is the village high chief. We had collected enough data at Off Da Rock that we were able to get the first sample and anthropometrics from Joe’s client, then drive to Pago Pago to meet Chilo. We had to leave Joe and the client with the post-test saliva collection tube and instructions on how to collect the saliva. Apparently, we neglected to tell them how to take the collection straw off the tube and screw the cap on, as we recovered the sample the next day lying on its side, wrapped in a paper towel, with some of the sample dribbling out. There was enough still in the tube to use, but the devil of data collection, like so much, is in the details. We drove to Pago Pago, and I had to drop Michaela off with materials for collecting demographic info and saliva, along with good cameras we had borrowed from the American Samoa Historic Preservation Office. A malu would take more than one day, so we planned for me to take the hand dynamometer and bioimpedance analyzer to collect data at Su’a Wilson’s tap-tap session and collect body density and handgrip strength from Chilo's client later today when I returned for the balance of the session or tomorrow when we returned for the inevitable second session. I drove to Leone and asked Michaela to text me when she got picked up and their session started. The session in Leone started almost immediately. I barely had time to get set up and collect anthropometric data. Su’a’s stretcher, his son Mark, had them ready to go. I sat behind Su’a’s wife Reggie and watched as she fanned everyone, comforted the client, and chatted with everyone. The hours went by, no text. Finally, “still waiting.” That was both a relief and distressing. Su’a took 2 ½-3 hours to complete a tauvae or band around a girl’s ankle. It was her first tattoo, and her mother, who had grown up in American Samoa, had brought her to get it as part of her heritage. As I drove back to Pago, I texted Michaela. She was still waiting for Chilo but had tracked down his wife and was sitting with her. When I arrived, Michaela and Chilo's wife and their baby were sitting at the picnic table where we had talked to him and where I had left Michaela waiting 4 hours earlier. There was a half-eaten package of Tim Tams. I introduced myself then Michaela asked me to give them a few more minutes to talk alone. I wandered around for about 30 minutes until Chilo's wife left. Then Michaela told me to drive to a nearby Japanese place for dinner. Chilo was not doing a malu today after all, but he had another tattoo job and would be calling us. Does anyone at this point believe that he will be calling us or that he will doing any sort of tattoo? Neither did we, but we did eat nearby, if only to be able to process what was going on and get some food in us. After several hours of calling Chilo and having him say he was on the way, Michaela called his wife. The Samoan islands are very traditional and very gender stratified. One of Michaela’s cardinal rules of research there is that she will not form friendships with males. It is too fraught with gender disparities and opens everyone up to accusations of impropriety. If she must work with a male in some capacity, she goes to lengths to get to know the wife as well. So Michaela called Chilo's wife to forge a relationship, since she was allegedly going to be working in Chilo's studio without his wife present. Michaela’s instincts in this regard have been as accurate as her sense that she should bring a male researcher on—me—to be able to talk with high chiefs and other males in her primary research, the impacts of social inequalities on unwed mothers and their babies. American Samoa and Samoa still retain their traditional, male-dominated, village-based political structures for the most part and to varying degrees. They share the same culture and language but, for the past 100 years, slightly different colonial histories. In the early 19th century, missionaries took firm root on all the Samoan islands. It was just before and during this period that several paramount of high chiefs sought to extend their power over multiple islands, using European trade goods acquired by converting to Christianity toward these ends. It was through these political and economic pursuits that Samoan and colonial interests became entwined. It was the son of the first successful missionary who established copra as a trade item, which is dried coconut from which oil can be extracted. Flourishing copra plantations were established across the islands, especially the bigger and more agriculturally accessible Upolu. A German trading company moved in and monopolized this industry and was so successful that when the business failed in Europe, the German government bailed it out to retain the income coming from Samoa. However, German treatment of natives was poor and exploitative, and, in an effort to retain control of their own lands, chiefs in Tutuila sought protection from the U.S. government against German incursion by offering sole use of its prized deep sea harbor at Pago Pago. The U.S. resisted for some time but ultimately became embroiled in Samoan affairs and recognized the need to prevent German colonial expansion throughout the Pacific. A naval standoff between U.S., German, and British ships that nearly came to head was prevented by a sudden hurricane that scuttled nearly all the ships at anchor and killed hundreds of men, forcing a quick negotiation that resulted in the Germans holding Western Samoa and the U.S. Eastern Samoa, later named American Samoa. Western ended up in the hands of New Zealand after World War I, and then became independent in 1962. It changed its name from Western to Samoa in 1997, much to the consternation of American Samoans. American Samoa was managed by the U.S. Navy beginning in 1901. After several failed efforts to install kings of Samoa during the earlier colonial trade period, the U.S. opted to follow the German governing style of allowing Samoans to govern themselves at the village level as they have always done, through a hierarchy of selected matai and a government-selected mayor or pulenu’u. A gathering of representative chiefs or the fono met regularly to discuss issues with the governor, who for the first 50 years as a U.S. territory was a U.S. Navy officer, then an appointed U.S. politician sent to American Samoa, then, beginning in 1978, a native Samoan elected by Samoans.

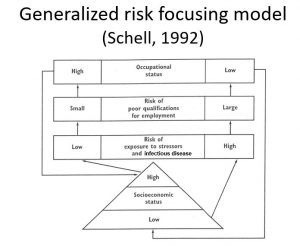

Most people in the U.S. are likely unfamiliar with American Samoa and even the most educated would struggle to find it on a map. American Samoa is the southernmost U.S. territory and is closer to New Zealand and Australia than it is to the U.S. Its strategic purpose relative to, say, Hawai’i has always been limited and, thus, it is in many ways unsullied by modernization. On the other hand, American Samoa is as sullied a territory as there is in other ways. American Samoans having the ignominious distinction of being among the most obese peoples in the world. Samoans have been studied to death by scientists because of their interesting Polynesian ancestry and large phenotype. Aside from the high rate of obesity, Polynesians in general and Samoans in particular are a large-bodied people. Samoans are much sought after as American football players and New Zealand rugby players. Yet because of modernization and a switch, especially in the less agricultural islands of American Samoa, to reliance on trade and, more to the point, U.S. subsidies and aid, American Samoans have transitioned to diets of commodity foods high in calories and low in nutrients and suffer high rates of the diseases of civilization, including obesity, as well as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease. When we dig down a little deeper then, we come back around to John Enright’s noir depiction of the American Samoa Michaela invited me to help study last summer. When a society is highly patriarchal, highly Christianized, and is almost completely reliant on U.S. aid, NGOs, and family remittances, what social group is at the bottom of society suffering the most? Poor women, women with little family support, women with little family support and no husbands, women with children and little family support and no husbands. Of course, this is a synergistic type of situation, one created by the structure of the society as it has developed. Poor women are women without titles in their family. They have no access to village-level resources unless chiefs allot it to them. There are so many political and ritual obligations to become titled and among titled families that resources do not generally circulate much beyond them. Except when a fa’alavelave is held, and there are a lot of them. For each fa’alavelave, chiefs might demand that everyone in the community contribute, especially the family at the center of the celebration. So if a low-rank woman and man want to get married, their families are expected to pay lots toward the celebration. Of course they are also paying, like everyone, toward everyone’s celebrations, so it will take them a long time to have enough money to be able to get married. In the meantime—whoops—they have a baby. American Samoa has the worst condom education of any tribe, territory, or state in the U.S. Sex education is verboten because of their strong, conservative Christian identity and values. Which is a double-edged sword, since this young woman is now pregnant. So she gets in trouble with her village and her church and is literally ostracized from both. This is how she becomes the lowest echelon of society with the most suffering. Often, to save the family from shame, the woman will be taken to Samoa or the U.S. mainland to have her baby, which is then raised by a family member. Secrets are kept. Shame is hidden.

Which brings us back to Chilo's wife. She was mystified as to why he had told us he was doing a malu. He had never done a malu before. He didn’t do hand tap tattoos. He hadn’t done any tattooing in months. He worked so many hours a week at the Family Mart, he could not afford to take off the two days he told us he’d taken off to do the tattooing. He hadn’t told her anything of his plans to meet with us that day and never told her about his extracurricular activities, though he had told her of meeting with us previously and of our interest in his tattooing. He did seem to do tattoos occasionally, but they did not bring in much money and he needed to put in as many hours at Family Mart and ensure his job there. They were barely hanging on. She’d had two children by another man before him, a man now in prison. She couldn’t afford food for those children, so she tried to breastfeed them both and suffered maternal depletion syndrome. She liked how it made her so skinny and attractive, but it was not enough food for the children. They were starving, and her family told her she should take them to an aunt who could care for them. She used to visit them there more, but her aunt chastised them for showing the kids too much affection, as if she wanted them back. She had to pretend she was not their mother, so the aunt would continue to care for them. And now she and Chilo had this child to care for. She did not know why he had told us his studio was right across the way from Pago Plaza. He did not have a studio that she knew of, and they lived far up the mountain off the road. He called a few times throughout this conversation. No, the malu was not happening today. But another person had made an appointment with him. Stay there. He would be tattooing later tonight. We could come to the studio and see that tattoo, take photos. We had explained the entire study to him in words we thought he understand, had given him copies of the consent forms in English and Samoan. We had asked him if he understood and he’d said yes. But to his wife he said he didn’t know we wanted to collect saliva samples. He wanted us to take photos. He thought we were taking photos. He thought we were writing articles and would bring attention to his business. His wife explained to him and said his English was not all that good. She was not sure how much he could read or understand.

This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed