|

I spent the week of UA's spring break in Samoa to get the project I was awarded NSF funding for in 2020 started finally. I spent 5 weeks this past summer in Honolulu talking with the Samoan diaspora community and had intended to collect similar data in Samoa via coordinated training of research assistants at the Centre for Samoan Studies at the National University of Samoa. However, having only arranged these relationships via email, I could not wrap my brain around how I was going to accomplish those things, and, after chatting with Jessica Hardin, another anthropologist who works with CSS for research in Samoa, I realized the best strategy would be to pay for an extra plane ticket and make the trip to have some meetings in person about the project.

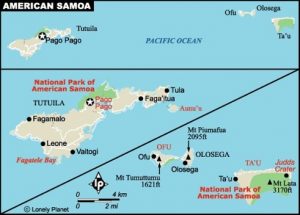

I stayed at the Samoan Outrigger Hotel because it cost about as little as a cheap AirBnB and is located close enough to the Samoan Cultural Village, where Suluape Tatau do hand-tap tattooing, and the National University of Samoa, where I would be giving a talk and have meetings. I went down to the Cultural Village right after I arrived, but no one was tattooing so I popped into a bar overlooking the Village and Apia Bay to see who was around. It was happy hour and full of Kiwi expats talking about their schemes to make money. Felt like a James Michener novel, but I guess everyone needs to make a living. The flight there is super long, and Samoa is 18 hours ahead of US Central Time, so I left on Sunday at 2PM, but I didn't arrive in Samoa until Tuesday afternoon. But I didn't have any appointments until Thursday, so I tried to find everyone on Wednesday. I walked around looking for NUS and CSS for several hours, and I finally found everyone I was looking for after getting thoroughly sunburned and foot-blistered. My stupidity for forgetting a hat, sunscreen, or my already broken in slides. I found Dionne Fonoti in CSS and the main offices and met a few other folks over there. Then I walked down to the Cultural Village and found Ata Sulu'ape tattooing. Junior (Paul) was in Pago Pago, and their father Alaiva'a was at home. Ata told me their father doesn't come down to the Cultural Village anymore, and I didn't have a car so didn't seem him while there. However, right as I was leaving, his daughter Patricia saw on FB that I was in Samoa and sent a message, leading me to realize I could have reached him through the daughters. I didn't think of it though, so next time. On Thursday, I gave a seminar talk about the research I've done and tried to describe the goals and methods I am planning for the Samoa project. The seminar was very well attended with lots of great questions and several people excited to potentially work with me. More on that in a paragraph or so. On Friday, I had some meetings to determine, now that my plans were somewhat clear, how CSS and I could help each other. Much of it revolved around who would be available to take on extra work. I'd be training and paying the person or people, but NUS does have have biological anthropology. They have cultural and language studies and archaeology. There was a medical doctor who is president of the Malofie Association, which is an association of people with the pe'a. I've been trying to catch up with him ever since, but he's super busy as a surgeon and director of the teaching medical program. On Saturday, I had a fruitful breakfast meeting with Dionne, her partner, and Greg Jackmond, the archaeologist at CSS. We talked a lot about the tatau project and generally got to know each other, but I also got the opportunity to hear about some amazing archaeology and bioarchaeology material they have that they're looking for help analyzing. So now, as part of our exchange, I'm trying to find students and colleagues who could help them with this analysis or who may be interested in doing archaeology research there. Contrary to my beliefs that anthropologists have been studying Samoa ad nauseum forever, it's really that anthropologists have popped in now and again and written books but never maintained a constant presence. The archaeology that's been done there has languished since the 1970s, save the occasional study to reify the Lapita story of peopling the Pacific. It's really still unknown why people migrated there or spread out and migrated from there to other Polynesian Islands. However, they have LiDAR data indicating Savai'i was once extensively inhabited, and there is tons of evidence of prehistoric habitation that is completely unexplored. Sunday is the day of the Lord, so no meetings. Frankly, most Samoans are so booked up with chief, village, and church responsibilities on the weekends that they're more busy than during the workweek. So I spent Sunday watching Alabama play basketball (in March Madness, the Saturday night game in Alabama was Sunday morning in Samoa) then went to a hike up to Robert Louis Stevenson's house and grave again. I'd been there last time but got caught in the rain. This time I walked in intense sun and got another sunburn. Monday was the day I was supposed to leave, but since the flight was at 8pm, I had time for some more meetings, which was providential. I had breakfast with Bernadette Samau-Sila, who is a Lecturer in Finance and Marketing. She's Samoa-born but raised and schooled in New Zealand. Shes a qualitative researcher whose methodology is perfect for the study I've proposed, which is why she reached out. She's done some research on the malu and just loves research, and I'm really looking forward to combining our ideas to make this project better. I headed back over to NUS with her after breakfast and went to see Greg's LiDAR maps, which I then played with for several hours until I needed to get to the airport.

0 Comments

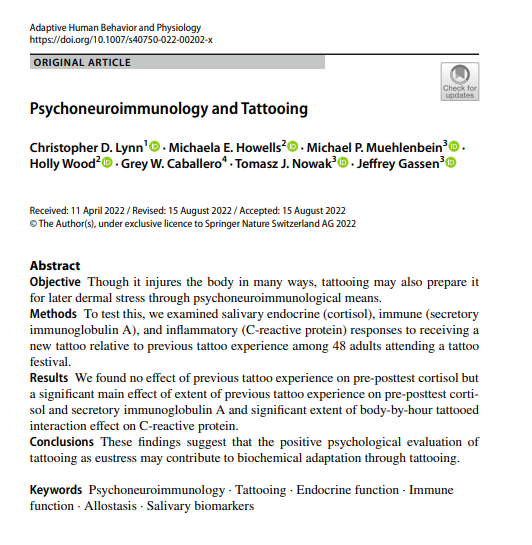

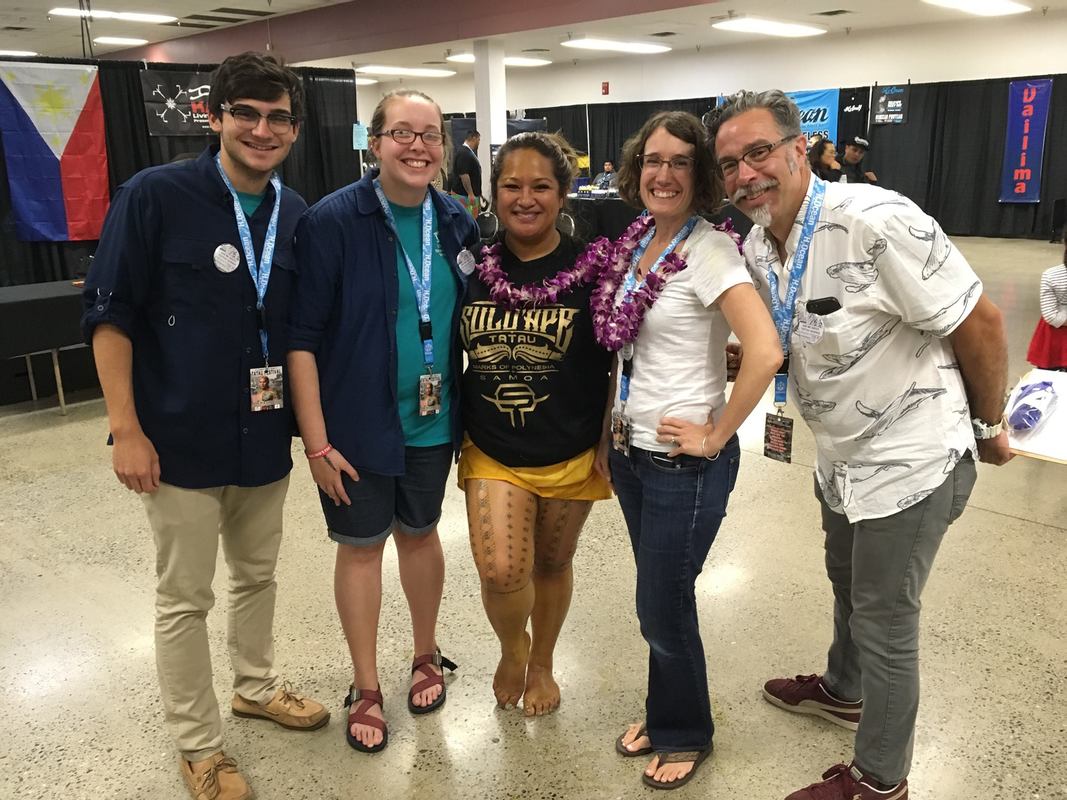

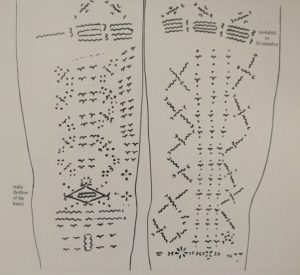

This new article is based on data collected at the 2017 Northwest Tatau Festival and is the first publication of analysis from those data. Summarizing the article in one sentence: "The psychological and physical experience of being tattooed may contribute to physiological adaptations that prepare the skin for other injury." Click on this link to the full PDF. Below is a slide show of photos from the tattoo festival for your enjoyment while reading.  I was impressed with the Polynesian Cultural Center. It seems like a cultural Disneyland, but it's owned by the Mormon Church and staffed by Brigham Young University students. So on the one hand, we expected the cheesiness that apparently appeals to tourist; but on the other hand, we expected religious messaging to mar the presentation. I was impressed with the limited amount of cheese and the complete lack of religious messaging anywhere that I could detect. What I know about Mormonism comes from Rob Ruck's book The Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans in the NFL and Arthur Conan Doyle's A Study in Scarlet. Of course the first is recent non-fiction, while the latter is an old fiction book. But the upshot is that Mormonism doesn't operate the way Christianity does. I've known a lot of Mormons because of their missionary style. My impression is that they go abroad to do service work and set an example but do not actively convert. So a lot of folks like the cultural experience and go into anthropology. A Mormon kid we met had the pule tattoo, which he'd received to settle him down apparently, and he told us that Mormons don't prohibit tattoos. They usually advise against them, but they are OK with cultural tattoos, which is what they consider Samoan tattooing. This is different than what Samoan Mormon kids in American Samoa who accompanied a non-Mormon friend to get tattooed, but I haven't checked this anywhere else.  Thanks to Chris (middle) and his wife Patricia (not pictured) for hooking us up! Thanks to Chris (middle) and his wife Patricia (not pictured) for hooking us up! The great thing for us about the PCC is that we were looking for Samoans to interview, and the easiest way to identity Samoans in Hawaii without just asking (which can be weird and potentially insulting for a variety of reasons) is to go to the Samoan Island exhibit at PCC because each cultural island is staffed by students from that island. The catch is that PCC is expensive, and we didn't want to pay to go in and look for people to interview, especially since we were skeptical of this tactic at first. So we went back and forth between the main entrance and BYU campus behind PCC looking for folks and kept getting steered by to PCC. Finally, we went in and stopped by the kiosk owned by friends of Tricia Allen (more on her later), who promptly offered to comp us in for both the park and the evening show (this happened again later in the month when I returned with my wife--we arrived with malasadas the second time, but the effect was the same--having connections is the best!).  Fresh manapua was delightful but nearly as amazing as Leonard's malasadas (Portuguese donuts) that we picked up the next time. Fresh manapua was delightful but nearly as amazing as Leonard's malasadas (Portuguese donuts) that we picked up the next time. Picked up fresh manapua from Island Manapua Factory in Manoa, just down the road from our room in the East-West Center on University of Hawaii and headed over to TT's parents' house. We were there to pay respects to and watch Su'a Peter Sulu'ape tattoo. Su'a Peter is 8th generation tufuga ta tatau in 'Aiga Su'a, or 8th in a line (according to an interview I conducted with his father in 2019) Samoan master hand-tap tattooist from the Su'a family. The Sulu'ape family have maintained the Su'a tradition for several generations. TT grew up with the Sulu'apes, and she and Peter call each other brother and sister and each others' parents mom and dad. Su'a Alaiva'a Petelo Sulu'ape, Peter's father, explained things to me similarly when I interviewed him in 2019--he has many kids, some of whom are biological children and others he raised or helped raise. Football fans would recognize TT's last name, but I'm sticking with initials here to give her family some relief from the panoptical gaze of football fans. She is the manager of Sulu'ape Skinz, Su'a Peter's handtap tattoo business, and also married to the uncle of at least one professional football player currently in the NFL. In fact, if we'd have popped in on Friday instead of getting "grounded" in our field site by exploring a bit, we'd have met said football star, who was in town to see family and popped in. TT's daughter also goes to Alabama, and I run into her occasionally at the gym where we both work out. She is easy to spot if you know what a Samoan malu looks like.  Me (with mouth swollen from trying betel nut with lime) & Su'a Peter Sulu'ape Me (with mouth swollen from trying betel nut with lime) & Su'a Peter Sulu'ape TT's parents have a lovely split level home with an open carport in a nice Honolulu neighborhood near a military base. TT isn't home, but Su'a knows we're coming and greets us upon entering the carport. A fale is set up in the carport, and the carport has been extended with awnings to create space for viewers to set off to the side. Immediately upon entering are tables with chairs around it and several bags of McDonald's someone brought (everyone brings food, so there is food arriving all day). We meet Su'a's toso and wife. Su'a is the title and name of someone who apprenticed in the Su'a guild and who was gifted the title with tatau tools by a tufuga ta tatau. Toso is the Samoan word for the stretchers, who stretch the skin so Su'a can tap. The toso include ED, a Samoan language instructor who I had been trying to contact separately, as I had learned that he has the pe'a (traditional Samoan tattoo for males) and knows all the Samoan tattoo artists. Knows? He has been toso for Su'a Peter since 2009 and travels all over the world with him. Little understatement. The other main toso is Su'a Peter's brother-in-law, who received his pe'a in November 2021 and began working with Peter as toso. We all chatted for about 30 minutes. We inquire about learning the Samoan language and are told of ideas for an online Samoan language course that might interest us but also of an app we can use to learn words and how they are pronounced. He also suggests we listen to the audio version of the Bible in Samoan, because it has more Samoan words in it than any other translated document, and it's easy to put it next to an English translation to make sense of the grammar and syntax. As we're meeting everyone, they tell us they'd just been to Alabama. I knew Su'a and TT had been there but not this whole room of people. The whole crew, Su'a and his wife, TT and her husband and parents, both main tosos, and TT's nephew had all been to Texas in March and had come to Bama to visit TT's daughter. We were supposed to get together in Bama, but our schedules didn't line up. The funny part is that got a tour of the athletic facility, including Coach Nick Saban's office. They got to sit in Saban's chair and try on his championship rings! Let me put this into context: Su'a and his wife and BIL all live in New Zealand. BIL is a rugby fan and doesn't even watch football (there is a time zone issue even the poor people of Hawaii have to deal with--noon kickoffs on the east coast is 6 am for them--that's a dedicated fan who gets up at 6am on Saturday), but he got to sit in Nick Saban's desk chair and try on the championship rings. I am a full professor at the University of Alabama, and I have not even seen inside Nick Saban's office. (Though if I'm being honest, I haven't tried and haven't toured the Bryant Museum or toured the athletic facility since I was hired in 2009, before any of Saban's championships or Heisman trophy winners, etc.). But I digress. Then Su'a and the toso went to work. There is a mat spread out on the ground for the tattooing area. Two big lights are set up behind the tufuga and fans are set up on either side to keep the bugs off and sweat down. There are customs to be followed to enter the fale: Everyone must wear ie (lavalava), shoes off, no hats or sunglasses, no video/photography/social media during sessions, and soles of one's feet should not be pointed toward elders. The toso stuff pillows into plastic bags, push all the air out, and tie them off for sanitary padding. Bandanas receive the same treatment and are used to support the 'au (the hafted tattoo instrument). Su'a Peter prepares the various 'au (which he keeps in multiple sizes in a traveling case) by tying the needles to the head of the tool. The titanium needles are soldered together and replace the traditional boar tusk that was previously carved. Boar tusk do not maintain as much sharpness, so I am told that tattooing with the titanium combs is faster, cleaner, and heals better than bone combs. To tie the needles on, he pulls out a long piece of synthetic string (like dental floss), holds the end on top of the needles with one finger, wraps the string around 20-35 times, places a small loop of string on top, passes the end of the other string through the loop, wraps it a few more times, and pulls the loop out, which tucks the end of the string into itself without the need for a knot.  No photography, video, or live streaming during tattoo sessions, so I drew a sketch to remember the layout. No photography, video, or live streaming during tattoo sessions, so I drew a sketch to remember the layout. Now is time to start tattooing. The tufuga and toso sit cross-legged on the mat with their first client between them. The first client is a Samoan guy who came by himself from across the United States. The "by himself" part is a bit of an issue, since they're told to bring someone who can help wash them and massage the tattoo to prevent scabbing and infection. Mike (UA doctoral student Michael Smetana was my research assistant on this trip) and I move to the floor so we can watch more closely. The chairs need to be moved to the opposite side of the table away from the fale. Su'a begins marking the arc that will go on each hip. Yesterday, he started with the pe'a (bat) on the back. Today one flank, tomorrow the next, and so on over 5-10 days, depending on the number of clients. Today, he's working on parts of four pe'a and doing one whole malu. Su'a works on him for around two hours. We listen to the Sulu'ape Skinz playlist they have prepared for work, and the sound of the sousou tapping on the 'au gives a second backbeat to the music. (I always come home with a few new tunes or artists to add to my own playlists--this time it's The Five Stars and Mr. Tee).  Plumeria tree, which grows all over Oahu, is a main source of flowers for lei. This is part of TT's father's garden. Plumeria tree, which grows all over Oahu, is a main source of flowers for lei. This is part of TT's father's garden. TT comes home around 11:30 AM and beckons us to the back porch area. We slip our shoes on, walk around to the back, and she shows us the yard and such (including a baby 'ava tree!). They have a giant mango tree growing in the back, and occasionally one falls, making a loud boom on the plastic roof, before it drops into the yard behind the fence and rolls down the hill! Fortunately, they must rescue enough that TT sent us home with four juicy mango. We sat in the back area chatting because it's difficult for most people not raised to it to sit cross-legged on the floor for long and because it's rude to carry on with conversation next to them tattooing. TT caught us up on their travels schedules, COVID19 issues, etc. We learned, for instance, that tattoo shops were closed for 1.5 years, so many never reopened or had to go underground to make a living. Soul Signature, the shop of Samoan-Tongan tufuga Su'a Sulu'ape Toetu'u Aisea, closed its street-level shop and moved to a high-rise, where they do work by appointment only. I had originally met Su'a Peter at the same time I met Su'a Aisea, when I stopped into Soul Signature on a Hawaii stopover just to get a sense of Polynesian tattooing in Hawaii. We were going to pop in again until we saw on their website that they weren't doing walk-in business anymore, but I had no idea they'd moved. ED comes back to talk with us and stretch out his back. The strain the tufuga and toso put their bodies through to sit on the floor for 8-16 hours is epic, and they pay the price. Other things I learned that I can share here: Su'a Paul Jr. Sulu'ape (Peter's brother) has gotten remarried, and they have a one-week-old baby boy. So I sent him a belated happy father's day via Insta, since I'm not able to get to Samoa this year.  Sketch of Su'a Peter Sulu'ape & two toso (stretchers) Sketch of Su'a Peter Sulu'ape & two toso (stretchers) In addition to all the food people bring, TT makes sure they have whatever Su'a and the toso need, so there are flats of soda, water, Gatorade, Monster, Alohas, and canned cappuccino. I down a Monster while we chat, then we go back to the mat to watch the next pe'a. We watch this one all the way through, picking up the hand fans to help out keeping the bugs off. Afterward, the man's wife asks us what we're doing and chats with us about the importance of religion in Samoan tattoo. I'm fascinated and will be processing that one in my brain for a while. That in addition to a comment made that Samoans in Hawaii who belong to a Samoan church maintain the Samoan culture, and those that aren't members of a Samoan church do not, because it is the churches were the center of village life in Samoa. Everyone sits around the tables to eat some food while they take a break. I have a manapua and a can of cappuccino. Much better than the manapua I ate for dinner out of the nearby 7-11 on my first night, since nothing else was open by the time I was dealt with by the rental car company (just a little double-bind in which first my travel agent booked my rental car for the layover airport instead of the final destination, and then I forgot to renew my drivers' license before leaving). Then the other brother gets the same part of his pe'a done, which we sit and watch until around 4 or 5. Then it's time for dinner. Su'a invites Mike and I to come sit with him, and they divvy up the dinners that the two families have brought for everyone (part of their responsibility). Food is also prepared upstairs and brought in. There is a steam cooker of white rice and a meat and veggie soup. The meals are teriyaki chicken and beef, garlic shrimp, and white rice with macaroni salad on the side (to keep it cold). There are several containers of poke in coconut milk as well. After each client finishes their session, they go into the shower that is set up via a hose in a tent in the back to wash and have the tattoo massaged. After this, they help clean up the food then leave. Another family will have arrived in the meantime and are preparing for the next session. Between each client, the toso roll up the mat from the previous client, tear the bags off the pillows and replace them with new ones, strip the needles off the 'au and autoclave them. Su'a puts newly sanitized needles on with fresh string before each client.  Two more sketches of the fale in the carport Two more sketches of the fale in the carport After dinner, Su'a administered a malu. Aside from making the initial arrangements and making sure the client arrives with everything they are supposed to bring, TT stays out of the art and technical aspects. So she was speculating with us as we took a break after the first leg of the malu was completed to chat. The client's father was from American Samoa, as attested by his ie, which was a tailored ie faitago with pockets and belt loops, as opposed to ie lavalava, which is called sarong in other places. This ie also suggested he might be a church leader, as the style and pattern are associated with them. Furthermore, as Tracy indicated, the double malu (the malu is the whole traditional tattoo worn by women in Samoa, but it is also the name of the main symbol of the tattoo, a diamond on the back of the thigh) is reserved for daughters of priests and similarly high-ranking people. And the mother of the girl was also wearing a dress associated with church leaders' wives. She said she thought the girl's father might be a bishop. Initially, my eyes had been drawn more to his Michigan Wolverines shirt, so I'd been planning to talk football if we started chatting. I met both of TT's parents while we were there, and they were very gracious and lovely. Her mother especially came down to watch and chat and was very generously teaching us Samoan words. She told us about her son the inventor too. He invented a toilet seat that sanitizes itself called "Washie." It's pretty ingenious, I gotta say. We've all struggled with those paper rings that we place on public toilet seats--the middle part falls in the water, gets wet and heavy, and pulls the whole ring into the water before we can land our hinies on them. Furthermore, public toilets during COVID19? Fuggetaboudit. So he invented a toilet that squirts sanitizer on the seat that you just wipe off with a little piece of toilet paper. Genius! TT was going to be the distributor (she has a few jobs), but they have licensing interest from a big public toilet company. The money is in the liquid to refill the toilet seat, so maybe Washie will be the next Harry's or something. Why not a subscription for Washie refills? When the malu started back up, we scooted back down onto the mat to watch, though by this point our hips were screaming so badly it was difficult to sit there. Don't get me wrong--tattoos are painful, very painful sometimes, and I found the handtap style even more painful than electric, though I admit it's been many years since I got an electric tattoo--but the real pain being experienced in that room is by the toso and, to a lesser extent, the tufuga. The Old Man, as all his family respectfully refer to Su'a Alaiva'a Petelo Sulu'ape, grew up sitting cross-legged everywhere and seems to suffer not at all. Su'a Paul Jr. told me how painful it is for him, that the numbness causes him problems. TT worries for Su'a Peter's health, not just because of the posture he maintains, but the long days he works. Those of us unaccustomed simply cannot hold the posture for long after the first hour or so. I switch my legs back and forth to ease pain. The mat chafes the sides of my feet, so I wrap my arms around my knees and hold them up. Later, all I can manage is to fold them under me to either side and switch back and forth. By the end of the 16 hours stretch, I had to do it very slowly because spears of pain would shoot up through my back, and I was trying to keep my poker face. Other toso popped in for shorter stints, and TT's husband came in during the 2nd or 3th pe'a as a 3rd stretcher. I can see it causes them all problems to sit that way, and it is something we all note and comment upon over the course of the days' sessions. Because this client got the double malu (malu is technically a specific pattern within the larger tatau, as the pe'a is the bat image of the male tatau, but the whole piece is also called pe'a), it took a little longer than usual, and Su'a finished her up around midnight. Even though they'd told us that he was doing parts of four pe'a, I couldn't imagine him starting another piece that late or of the person showing up ready to be tatted at that hour. But he did, and he did. Apparently, he has TT book up to five pe'a at a time sequentially in different cities, so he works under deadline and maintains his timeline hell or high water. Apparently he'd been at it till 6 the night before and 3 another night and had even worked on Sunday, which is unusual. We stayed until 3 when they wrapped up, but we did not go back the next day at 9 when they started up again. #Beastmode By the time of the last pe'a, Mike and I were both brain fried. I was groggy from dinner for a while, then started to get a headache, as the pain from my ass radiated up through my body. Around midnight I drank a Coke, ate two donuts (at our donut break), and drank a full cup of cold McDonald's coffee of the six that had been brought over earlier in the day. Helped my headache. By the time of the end of the malu and the last pe'a, my hips hurt so bad that I'd moved up to a chair behind the table. However, Su'a Peter kept an eye on everyone throughout the proceedings. When he wanted anything, he'd whisper to a toso who would turn and ask anyone but Mike or me. I think that was out of respect, but at one point I awkwardly asked him at his own house if there was anything I could get for him, just so I could feel useful. One of the things I love about working with Samoan tufuga is that he chats with the toso the whole time they work, and they laugh a lot, and I like joking around with them too. They have great senses of humor, so it's easy to cut up with Su'a. However, one of the things I don't love is that I don't know their language and so want to know what they're laughing at and never do. So there is always a bit of awkwardness in trying to relax into a situation wherein everyone is laughing but you and you have no clue what the joke is. Anyway, Su'a is keeping an eye on things, so I don't want him to catch me drifting off in the chair and bust my chops over it, so I slip back onto the floor for one last stint, figuring the pain would keep me away. Somewhere along the way I read that Samoans consider it rude to sit and write things down in front of people. So they will listen politely and, if they need to write something down, they do it after the fact. So we don't take as many notes during these sessions as we would if we didn't care about appearing rude. I say this by way of noting that there are several things I learned or that people said, but since I wasn't taking my scratch notes on pad in my pocket throughout the course of the night, I don't have an accurate recall of the order of all events. Not that it matters. Other interesting things I learned: Su'a Peter is collaborating with the same liaison I work with at the Centre for Samoan Studies at the National University of Samoa on Moana II! Su'a was the consultant for the tattoos of Maui in Moana, and they consulted him again on the script for the sequel, but they had Moana getting half a malu, then running away and leaving it unfinished until the third movie. That's something that wouldn't happen, and no one knows of it happening. The closest TT could relate was a girl who found the malu so painful that Su'a had to stop and send her home to recover herself so it could be finished the next day. Unfinished pe'a and malu are considered shameful to everyone--the tufuga, the family that paid for the tatau and put the person forward as ready, and of course the person. Unfinished pe'a are called pe'amutu, and one way to spot them is if someone has the pe'a peeking out of shorts at the knees but never takes their shirt off because they don't want people to see that they didn't get the pute (navel), which is the last part done and is in, well, the bellybutton. But that's pe'a, which takes like 30-35 hours, as opposed to the malu, which is 3-6. No island girl would run away with an unfinished malu for more than one evening if that, so Su'a Peter refused to be involved unless they fixed it from a cultural perspective. Cool, right? Su'a kept his ink in an Alabama coffee cup. I forgot to get a photo, but Roll Tide. So yeah, Su'a finished up at 3 am. We said goodbye to everyone, wobbled out, spent a few minutes discussing, then got to sleep so we could make our appointment the next morning to drive up to the pa of Kawika Au, a Hawaiian hand-tap artist I first encountered when he was stretching for at the 2018 Northwest Tatau Festival. But more on that next post... We're a little behind in our updates, so a few of these are dated...but without further ado.

This summer we ran a successful crowdfunding effort to fund the first half of a second field season to study Polynesian tattooing and immune response. I attended the Northwest Tatau Festival in Seattle/Tacoma, WA, where we collected data from 52 participants. Next step is to gather the funds to analyze the samples! I am excited by the prospects of returning to the field next summer to do more research, as I’ve been digging into relevant theory in cultural evolution that is, I believe, spot-on in outlining what is going on with the resurgence of Pacific tattoo cultures. I’m struck by how completely so-called traditional tattooing practices were quickly purged from many Pacific cultures in the 19th century. (I use the term “traditional” as shorthand, since Pacific cultures have maintained tattooing practices to varying degrees during this period and never been isolated from the influences of each other or outsiders—according to Samoan poet and activist Albert Wendt, as quoted by anthropologist and Te Papa Museum Senior Curator of Pacific Cultures Sean Mallon in “Against Tradition”—there is no such thing as “traditional.”) Mind you, we all know what shits missionaries and colonial agents were in trashing native cultures, but it wasn’t one-size-fits-all trashing. For instance, the French were more interested in trade alliances than enforcing decorum, such that it appears many French colonials got tatted up in native styles to show their sincerity (e.g., Bienville). It’s like when our ALLELE guest speakers throw out a gratuitous “Roll Tide” at the beginning of their talks to ingratiate themselves with the audience, except, well, way more committed to their cause (I wonder if LSU ichthyologist Prosanta Chakrabarty will say “Roll Tide” this week when he gives his talk two days before Bama whips LSU’s patootie…). https://twitter.com/PREAUX_FISH/status/1055465915033247744 I’m a few chapters into reading Makiko Kuwuhara’s 2005 ethnography on tattooing in Tahiti (efficiently titled Tattoo: An Anthropology), and she notes that Tahitian tattooing almost completely disappeared right out of the missionary gate in the early 19th century (perhaps why we don’t see any tats in any of those Gaugin paintings). Tahitian tattooing reappeared like it did in the mainland U.S., among fringe and “deviant” types and in similar motifs. Then, what is so fascinating to me, traditional tattooing was reintroduced by Samoan tufuga ta tatau (tattoo masters). I am imagining the Samoan tufuga who reintroduced traditional tattooing to Tahiti was the Sa Su’a Sulu’ape guild, but I haven’t read far enough in to confirm. However, based on our ethnographic interviews with tatau historian Christian Ausage in 2017, the Sulu’ape branch of the Sa Su’a guild was all that remained and that persisted of traditional Samoan tattooing. Sulu’apes have, as far as we can tell, ensured that the Samoan tradition remained unbroken and taught all active Samoan tufuga today. At least this is one of the things we’ll be investigating. Some of these answers are no doubt in the new book by Sean Mallon and Sébastien Galliot, but I have yet to get my hands on a copy.  Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author). Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author).

I am imagining that a variety of environmental/social factors are at play here, which, in theory, we can mathematically demonstrate with the data in hand. Joe Henrich, Bob Boyd, Pete Richerson, Christopher von Lueden, Alex Mesoudi, Maciej Chudek, and others I’ve been reading over the past few weeks make the case and provide the models we can use to test a few predictions in this regard. Robert Shaffer’s giant coffee table book American Sāmoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag indicates that tattooing and other native practices were banned by missionaries in Samoa but that Samoans just tended to compartmentalize and ignore some of those dictates, while becoming über Christian. Some have derisively called Shaffer’s history a biased account of governmental propaganda, but he was good friends with several Samoans I’ve come to respect immensely, such as Reggie Meredith and Wilson Fitiao, so I don't dismiss it out of hand. The book essentially indicates that, in the mid-19th century, American Samoa asked to become a territory of the U.S. so German mercantile companies did not take them over as was happening with Western Samoa. According to the book, Germans came into Western, set up trade, took land from native peoples, made tons of money, were pricks, and that led to the infamous standoff between British, U.S., and German navy ships that was interrupted by a hurricane (the summary of most brief histories of American Samoa). The colonial powers then simply divided the Samoas up instead of fighting over them, with Western Samoa going to Germany, Eastern going to the U.S., and the U.S. giving Britain Guam. After WWI, New Zealand was gifted Western, which became independent in the 1950s. After that, a quote from former American Samoa Historic Preservation director John Enright from his noir detective series (Fire Knife Dancing, in this case) based in American Samoa seems aptly to describe the circumstances, though it also brings into question the whole please-help-us-U.S. of Shaffer:

But I digress. The simplifying model I’m imagining (great quote from someone via Katie Hinde during her recent visit by the way—“all models are simple; some are useful”) is that:

Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption] Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption]

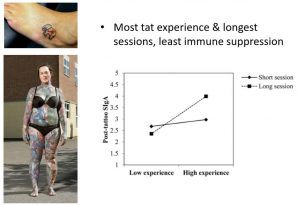

Among the sources I know I’ll be returning to again and again as I explore this, Joseph Henrich “Cultural Transmission and the Diffusion of Innovations: Adoption Dynamics Indicate That Biased Cultural Transmission Is the Predominate Force in Behavioral Change.” I think everything we need to know right now is right there in that title. [Nerd drops mic] Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We had worried when the study started that we would have difficulty juggling multiple tattoo sessions with only two researchers because we only took along one bioimpedance analyzer (BIA). The study protocol is ultimately rather simple. It involves a short questionnaire about tattoo experience and some basic demographic information, then we collect hand-grip strength using a hand dynamometer, body density using a BIA, and a saliva sample right before the tattoo starts, noting the time, and another as soon as the tattoo concludes. From the saliva samples, we extract immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Immunoglobulin A is an antibody that lines the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract and is a frontline defense against common infections like colds and flus. Cortisol is a stress hormone that increases when the body or mind are responding to a stressor, like getting a tattoo. Part of the classic stress response involves turning off non-essential functions to deal with the source of the stress until the body can return to homeostasis, and the production of IgA is one of the things usually suppressed during stress response. But as we point out as part of our induction protocol, the body can become habituated to certain types of stressors and have mediated responses. Take exercise, for instance, which stresses the body and results in immunosuppression when a person is new to it. With regular exercise, the body actually becomes healthier and is better able to deal with the stress of it, as well as daily potential insults of other types. Unless one overdoes it. Studies of elite athletes find they catch upper respiratory tract infections more often than most and suggest it is due to fatiguing this system. There is a growing body of research that finds overtaxed stress response systems result in deterioration in the body, including cognitive deficits results from apoptosis in the hippocampus. We collect body density as an indicator of fitness and handgrip strength as indicator of underlying neurocompetence. By controlling for these—essentially equalizing people for these variables—we can compare tattoo experience to the changes in cortisol and IgA from the beginning to the end of the tattoo. In our previous research, we found that people with little to no tattoo experience responded to being tattooed with the predicted spike in cortisol and immunosuppression of IgA but that people with lots of tattoo experience did not have immunosuppression. In American Samoa, the logistic catch was that we had one dynanomometer and one BIA between us. Ironically, for much of the study, because there are so few tattooists in American Samoa, there were two of us hanging out for the entirety of a tattoo session when only one of us was necessary, and not even for the whole session. We really only needed to be there for the beginning and end, except for the need and want to collect ethnographic data. As it happened, the same day Chilo said he was doing a malu was the day Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoos had a client and Su’a Wilson was doing the first hand tap tattoo we’d been invited to collect data at. Finally, we had the luxury problem of having come all the way to American Samoa to collect as much tattoo data as we could in 6 weeks and had to juggle three at once. But why did we come to American Samoa? If there are so few tattooists, why not conduct this retest back in the mainland U.S., where there are more tattoo studios in any given town than there are McDonald’s and Starbucks combined (American Samoa doesn’t even have Starbucks, though they do have Starstruck—however, they have two McDonald’s, one of which has been the highest grossing McDonald’s in the world several years running). We came to American Samoa to retest the model because you can’t generalize a scientific finding from 29 mostly women in Alabama to much of anyone else, despite the elementary nature of the finding (this finding, though compelling to media, is consistent with basic stress response and allostasis theory but cooler when applied to culture and especially to tattooing). And we came because the Samoan Islands have the longest continuous history of tattooing.

The myth of the twin sisters who brought tattooing to Samoa is a story everyone knows, though there are different versions of the story. The most common version is known because of “The Samoan Tattoo Song,” which one can hear regularly on Samoan radio. https://youtu.be/wIgCNQeZYBA

As the song indicates, women brought the tattoo tools because tattooing was originally the realm of females, but they made some mistake and ended up switching things around. The longer myth deals with the families who were given the tools, which relates to the guilds that are allowed to teach and apply hand tapping now. Ausage also believes the story originally referred to Fiti, not Fiji, which is short for the village of Fitiuta, but that it has been distorted and confused with time. When the first explorers recorded to have sited Samoa landed, they thought the Samoans wore silk knickers because of their pe’a, which are the male tattoos extending from midriff to below the knees. To be continued… This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity.  Full sleeve by Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoo.[/caption] Full sleeve by Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoo.[/caption]

Michaela and I were despondent from cancellations and because we were collecting data on day two of multiple sleeves (a full arm tattoo) at one studio. Meaning, we were collecting additional saliva samples from individuals we’d already got them from because they were getting big tats that took multiple sessions, so we were collecting pre- and post-tattoo data from day two and didn’t have anyone else we could collect new data from. We hadn’t really worked out what to do with additional data like that. In my previous study, I’d averaged additional samples in and found the additional data didn’t make much difference. We were likely wasting our time, in other words. So I volunteered to drive to the village of Ottoville, out past the Cost U Less, and pick up a family in town for a family reunion who wanted to get their afakasi son (half-Samoan—a distinction I make because Samoans make it, though it both does and does not seem to matter) tattooed and that needed a ride to get there. On the way, I stopped at the Family Mart to find this supposed Tongan.  Cargo boxes at shipping yard of Fagatago, American Samoa.[/caption] Cargo boxes at shipping yard of Fagatago, American Samoa.[/caption]

He supposedly worked in the cargo boxes, which are the shipping boxes that goods come in. Every Chinese and Korean grocer has them lined up in front of their stores. I’m not really sure why. Do they simply have stuff dropped off in them and trade them out, keeping them there for additional storage? I’ve never thought to ask. I also didn’t know people worked in them. But I stopped at Family Mart, didn’t see anyone around the boxes or any doors to knock on, walked around inside first, didn’t see any likely candidates, then went back outside to the car and saw a guy who could have been my Tongan coming out of the box. He had hair clipped short, looked Polynesian possibly but not necessarily Samoan (wasn’t big enough), and his arms were covered with tattoos (though not Samoan tattoos). He was coming out of one of the boxes carrying goods to restock shelves inside. [gallery ids="6419,6420,6421"] He had a dour appearance when I approached him. I asked if he was Tomesi or Ollie (names changed for confidentiality) and he said no. I asked him if he knew Tomesi or Ollie, and he shook his head no. I told him I am a researcher studying tattooing and referenced an article in the Samoa News and radio and TV interviews we had just done about our research to give my story credibility. So far, everyone we had encountered had heard or read one of these, because there are limited media outlets on island. Puzzled, I asked him if he was a tattoo artist, and he said yes. So I gave him my phone number, got his name and phone number, and asked if I could call him to talk to him about our study. He said yes, we arranged a time, and I left to finish my errand, elated by my success in the face of our flagging sampling. I had found the Tongan tattoo artist Niko had told me about, but his name was Chilo, not Ollie or Tomesi, and he had no Polynesian tattoos that I could see. However, even the tattoo experts often have tattoos they’ve collected elsewhere in their youths. I saw so many eagles, for instance. Granted, an eagle is on the American Samoa flag carrying a Samoan war club and fly-whisk, but there are no eagles in American Samoa. It represents the U.S. And Pago Pago. Though this is no different than U.S. teams being represented by Tigers. Fagaitua are the Vikings, for instance. I had promised to call Chilo at a time that evening. The idea that one show up on time to a meeting is a Euroamerican convention or what you do for work and church, not necessarily other situations. So I had the best of intentions of calling him later, but we were spent after our day of resampling the same person and decided to treat ourselves and our foul moods to a movie and dinner out with our friend David to cheer ourselves up. I didn’t notice until the next day that I’d received a phone call during dinner from an unknown number. Now in the mainland, I’m so phone phobic, I’d never call someone back who called me that I didn’t know and who didn’t leave a message, but people can’t leave messages on my cheap American Samoa Telecommunications Authority flip-phone, and who would be calling me? Only someone interested in or related to the research. So I called back, and it was this guy I met in the cargo box. That never happens. Chilo actually called me. We couldn’t believe it. So I arranged for us to meet with him in Pago after he got off work Monday, where he would take us to his house to talk and so we could find it for collecting tattoo data later.  David Herdrich is more than just a friend; he is Director of American Samoa Historic Preservation Office and one of the most important people on our American Samoa research team. David Herdrich is more than just a friend; he is Director of American Samoa Historic Preservation Office and one of the most important people on our American Samoa research team.

And here we were, sitting anxiously in our car, wondering if Chilo were some type of Tongan criminal, a killer preying on stupid palagi scientists who’d taken no safeguards. Since this is a true story that I am writing for an anthropology class and to describe fieldwork—and lest I reify any stereotypes, I’ll hazard a few spoilers—he was neither Tongan, I don’t think, nor, to my knowledge, had he any malevolent intent. This was all our imaginations, but stay tuned, because it was still weird. We finally voiced our mutual discomfort at sitting in an isolated parking lot behind a building in the dark in Pago and moved the car to a spot in front on the main road. There we sat a while longer. We called Chilo to check on his progress, and he told us he was on the way, almost there. Half an hour later, we called him again, and he was just leaving work...I finally gave him 15 minutes before I was going to leave. When 15 minutes was up, Michaela told me I should call him to tell we were leaving, but I just wanted to bail. Reluctantly, I did call him, and he asked where we were, saying he was in the parking lot and couldn’t find us. This freaked me out. How did he get by? I didn’t want him coming to get in the car or to come to the car window, so I got out to find him. He had come through from the back, and I met him back at the gate, out of Michaela’s sight. But he was nowhere as threatening in person as he had become in my mind’s eye, so I brought him over to the car to introduce to her. Fortunately, he also no longer wanted us to go to his house. Their pastor and his family were there, he said. It might seem odd that a church event was going on at his house, and he was in a dark parking lot with us talking tattoo, but it makes perfect sense in Samoa. We sat at a picnic table in the back of the plaza to talk. This was in a well-lighted area, and as we sat there, some Coast Guard palagis we knew happened by in their uniforms and chatted with us, which gave us additional relief. The story Chilo told us was exciting and incredible. He wasn’t Tongan at all, as I mentioned, but from Western Samoa. He had his own tattoo studio and business on the side, doing tattoos with electric gun and hand tap. He said he had been trained by a Sulu’ape. We explained our project in the slow manner that we do, because English is not the first language of many Samoans, using simple words, repeating certain things, focusing on the cultural elements, ensuring him that we were looking for partners in this study, not simply participants. We shared a copy of the informed consent, which outlined the study in simple terms, in English and Samoan. At one point, Chilo started crying, which was both surprising and touching. He said God had sent us to help him and his business, and he was grateful and happy to participate. The Samoan Islands are 99% Christian. The missionaries did their work well there. Though sometimes being Christian is a means to a social end, the structure of Christianity mapped well onto the village-based authoritarian structure that included top-down morality, and it flourished there. American Samoa is emblematic of anthropologist Rich Sosis’ “3Bs” model of religious commitment signaling. You can observe religious commitment via behavior, badges, and bans. People go to church all the time, wear elaborate clothing, and observe a hefty load of religious taboos. But conspicuously missing among these Bs, Sosis notes, is belief. It’s not necessary to demonstrate commitment, though it often develops simply by following through other three signs, as a way to minimize cognitive dissonance. Many Samoans are cynical about religion, but they are still Christian. I don’t know Chilo's religious values, but his statement that God had sent us to him came as no surprise. What did surprise us is that he said he would be doing a malu this week. It was like we’d bought the Willy Wonka chocolate bar with the golden ticket. A malu is the female counterpart to the pe’a. These are the special midriff and thigh tattoos that only Samoans are supposed to get and symbolize one’s commitment to village, matai (chief), and aiga (family). Malu means to hold together, and the symbols that characterize the malu include crosshatches, like the ties that bind the house together. They represent the importance of the Samoan woman in binding the family and village together. But tattooing is primarily a male domain, so, though we had seen several men getting pe’a, which has similar significance, we had yet to see a woman getting a malu. And Chilo wanted us to part of this tattoo experience. He would have us wear gloves and a gown and be in the inner circle of the tattooing with his stretchers. And he wanted us to take photos. The family would be OK with it, he assured us, and we would not be in the way because the family would be in the room outside. All of this was very exciting but also quite odd. First, all the tattoo artists on Tutuila know each other, as it is a small place. For that matter, most of the tattoo artists in the entire South Pacific seem to know each other, and no one knew this guy. Second, when we asked about hand tap artists, all the same names came up, regardless of who we talked to. Becoming a hand tap artist is no small thing, as it requires an intensive apprenticeship, and there are a limited number of people with whom one can apprentice, especially in the Samoas. If one is a Su’a and/or a Sulu’ape, one is known because one has started as a stretcher for years and been conferred a title with the tools and permission to tattoo. Sulu’ape is the family name and title granted by that family of master tattooists for completing a certain degree of apprenticeship, and Su’a is a higher title. According to historian Telei’ai Fanaea Christian Ausage, author of Laei a Samoa, a book about Samoan tattooing, Sasu’a is one of the ancient tattooing guilds and once associated with a specific family. The title is now roughly passed down by or within families, with whom the Sulu’ape family are associated. There is some tension and controversy now about the legitimacy of Sulu’ape as a family name versus a title and what it means and the linkage of the Sulu’ape to the Su’a guild, but as outsiders, these appear to be largely political and economic distinctions. The Sulu’apes have clearly cornered the market on hand tapping, and someone in their family has trained absolutely everyone else conducting hand tapping who is working today. We met Peter Sulu’ape in Honolulu and Paul Sulu’ape in Samoa and interviewed Chris Ausage about the hand tap artists working today. No one mentioned Chilo, we couldn’t find his Facebook page, even though he wrote down the title of it for us, and he didn’t seem connected to any of these tattoo networks. Furthermore, the idea that Chilo would be a trained Su’a and have his studio set up to keep family out seemed anathema to our experiences of the tap tap tatau experience in the open air fale (or house). At Soul Signature Tattoo in Honolulu, the Polynesian tattoo shop where we met Su’a Peter Sulu’ape, there were several Samoans who had come from Georgia, North Carolina, and Alaska to get pe’a, malu, and other tattoos. Su’a Peter and Sulu’ape Aisea Toetu’u conducted hand tapping in a back room, away from their standard U.S. tattoo parlor set up; but whereas families and friends sat at a distance in the waiting area while tattooing occurred up front, consistent with parlors around the country, family and friends were welcome and encouraged to gather round the person getting tattooed in the back, provided they wore an ie lavalava (the Samoan version of a sarong, worn regularly by females and males and expected in ritual and formal settings). And despite the distance, there were a few family members who seemed to have traveled just to be there while their family members received the pe’a and malu. In Samoa and American Samoa, family participates as skin stretchers at the tattooing in the fale of the Samoa Cultural Center, where we met Paul Sulu’ape and saw him working. Su’a Wilson Fitaou’s sons worked as stretchers in his fale or when he travels to the homes of others for the hand tapping we saw in American Samoa. Family and friends gather around, hold the hands of the person being tattooing, console and fan them, and massage their muscles to prevent stiffness or break up the bruising caused by the hammering of the tap tap. In no case were family kept separate from those being tattooed in our experiences to that point. To be continued... This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. PrologueInstead of syllabus day, I read this story on the first day of my Fall 2017 Neuroanthropology class then launched right into the class. I’d never done this before, but I like to think of the course as interdisciplinary and experimental and that different ways of experiencing materials is important. I was inspired to do this by anthropologist Katie Hinde, who wrote a story to start her human evolution course at Arizona State and blogged about it. Katie is a friend and colleague of mine. She is a contemporary but probably a few years younger than me. Nonetheless, she is trailblazer and someone I admire and look to for inspiration in how to conduct an anthropological career-life. You can find her work at MammalsSuck...Milk, a clever play on words, as her research focus is about mammal milk. This piece is about the fieldwork I’ve conducted the past two summers. I just wrote it the weekend before the first day of class, so, for better or worse, students heard an early draft of this story that may get published on its own somewhere or in a book some day in some form that will probably ultimately be very different than this. I wrote it because I think our work this summer epitomizes the nature of neuroanthropology as essentially biocultural, and because I think this story encapsulates much of our experience of fieldwork this summer. There may be less neuro than you’d expect here, given the course I read it to, but it’s the ethnographic prelude before we’ve finished collecting and analyzing the neuro data.

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed