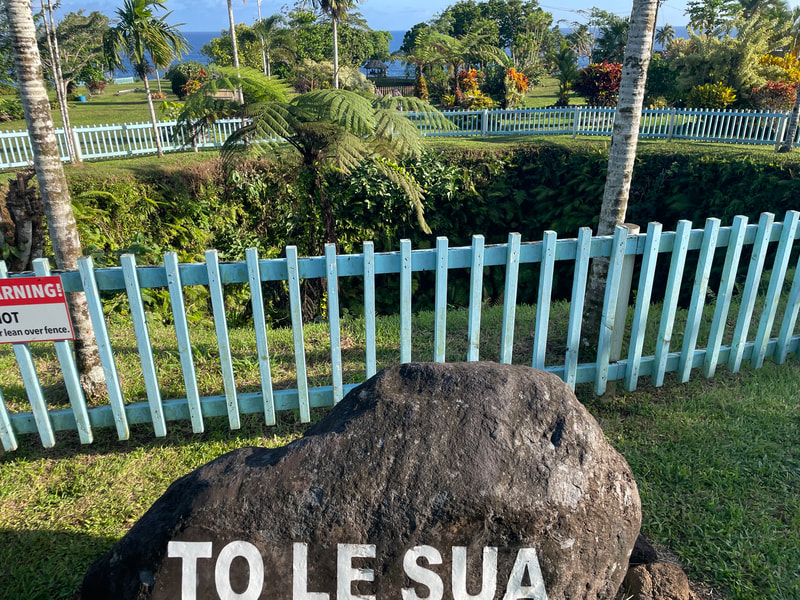

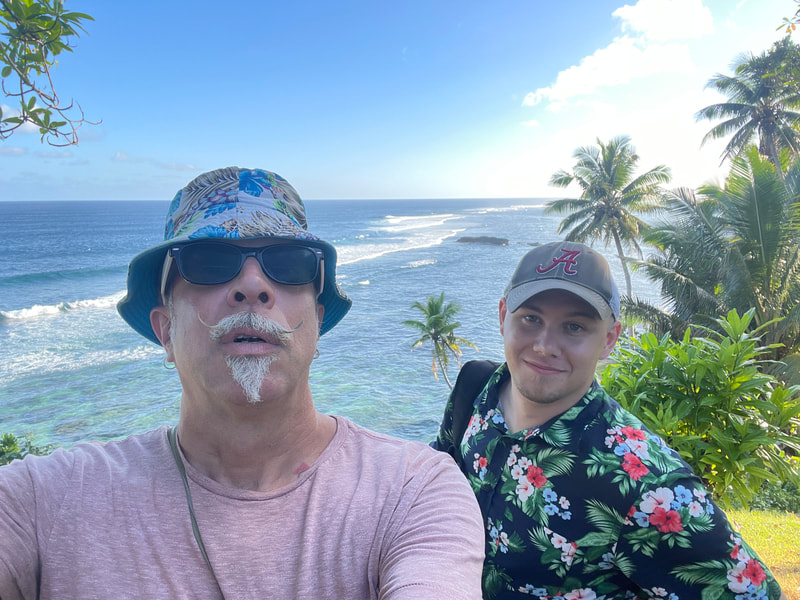

Centipede on back of pe'a tattoo. Tatau by Su'a Sulu'ape Paul Jr. (III), Sulu'ape Tatau, Apia, Samoa 2017. Photo by author. Centipede on back of pe'a tattoo. Tatau by Su'a Sulu'ape Paul Jr. (III), Sulu'ape Tatau, Apia, Samoa 2017. Photo by author. During our first week of the field season, we started on Saturday by meeting our housemates. The giant spider on the rim of the toilet wasn't nearly as startling as the giant centipede among the dirty dishes in the kitchen sink. I didn't have my glasses on when I got up to make coffee and thought it was an eel at first. Why an eel in the sink? I had no idea what it was and hadn't seen the size of the centipedes yet, but I ultimately recognized it as one of the main motifs in the pe'a tatau I'm studying! Sunday is the Lord's day in Samoa, and everything is closed for the most part. Apia is a city, so it's a bit different there, but there are many villages in Samoa where even driving through on Sunday would be unwelcome because of the requirement to rest and attend to village and church duties. We took the opportunity to drive around Upolu a bit so Grant could see the sites. We stopped by the waterfall off the Cross-Island, then cruised around the east end of the island, noting the burning of plant trash taking place in every village around 5. We capped the day with a nice meal of something Grant made from this and that. It was nice to have multiple cooks in the apartment for the field season.  Dr. Bernadette Samau & I meeting for breakfast back in March when we first starting brainstorming our collaboration. Dr. Bernadette Samau & I meeting for breakfast back in March when we first starting brainstorming our collaboration. We met a new collaborator during the week. Through my visit back in March, arrangements had been made for Leota Sanele to be our research assistant, interpreter, and cultural liaison. Leota is a tulafale (talking chief) from Savai'i, as well as a linguist in the Centre for Samoan Studies at NUS. In fact, Leota is his chief title, which becomes one's first name upon initiation. Leota is talking chief for the Centre for Samoan Studies and NUS as well, as we discover in a few weeks. More about him later, but the match for this project could not have been better. Together with Leota and Bernie, we revised the freelisting protocol for Samoa and made plans for data collection. Bernie would collect data on campus, Leota would collect data in Savai'i, Grant and I would travel around Upolu and recruit people, and Josh Naseri and the Olaga Project would collect data in Tutuila. Once we had the protocol set and paperwork revised (consent document in English and Samoan, data collection sheet in both languages), Grant Pethel (UA undergraduate research assistant) and I went around Apia looking for people to participate in the first step in the project. I began this last summer in Hawaii, when we couldn't travel to Samoa because of COVID-19. The objective was to ask people to write down all the terms that come to mind when thinking of a typical Samoan. We do this among our target group (Samoans in Samoa and the diaspora). In Hawaii, we just asked the questions verbally and gave participants tablets of notebook paper to write down terms. However, in Hawaii it was difficult to identify Samoans from other Polynesian people without weird/awkward profiling. Instead, we went to convenience stores in the known Samoan neighborhoods, to the Samoa Island at the Polynesian Cultural Center and to BYU Hawaii campus. Since all the terms we collected in Hawaii are from the Samoan diaspora, we repeated this activity on Upolu and Savai'i (Samoa) and Tutuila (American Samoa). I had planned the same activity in the Manu'a Islands of American Samoa as well, but we did not have time to travel there on this trip. Despite being in the Samoan Islands for 6 weeks, travel among the islands is difficult because of the limited boat and plane options and the advance planning needed to travel among them. Nonetheless, it was apparent that the terms from Samoans who had never been to Samoa were wildly different from Samoans who visited regularly or had migrated from Samoa. dGrant and I were most successful at the bus station and around the Cultural Arts Village, both of which are in downtown Apia. The bus station was great because there are hundreds of people waiting for dozens of busses to take them home to various parts of the island. The Cultural Arts Village was great because I have worked there before and know many of the people around there. We were less successful when we traveled around the island. There was one day when we saw groups of people watching rugby at a school, and we probably could have recruited several people there. However, we were exhausted by that point and couldn't must the energy for another cold approach. I thought we could stop at stores along the way and at a few of the tourist stops around the island, but there were very few people at any of the stores. Furthermore, those people were working, and it seemed rude to impose on them when working (though maybe that was naïve of us). There were many people at their homes in the villages and sitting on church stoops, but without a local Samoan person to advise, I wasn't sure it would be appropriate to approach people in their yards in the villages. Usually, village-based work entails meeting with matai (chiefs) and/or faifeau (minister), which we had not done. As a last ditch effort, we went to To Sua Trench, which is a collapsed lava tube that is used as a swimming hole and gussied up to make some money off tourists. Again, the only locals were working, so paid our money and went in, but with no one seemingly free to interview, we went swimming in the hole and checked out the other tourist-friendly features. Too bad we didn't have our masks and fins with us though because swimming in the lava tube was way cool, and I would have liked to dive down and explore more.

By the end of the week, our team had collected terms in Upolu and Savai'i and a few from American Samoa. We finished the American Samoa sample as we transitioned to the next stage and had to go back and confirm some assumptions made because of time constraints. When we had the opportunity to travel to Savai'i the weekend after Leota collected the terms, it would be our only chance to conduct the next phase of research, so we had to proceed even though we had not yet confirmed saturation in Tutuila. Fortunately, when we received more data from Tutuila, there were no new terms that were mentioned with enough frequency to have made it to the next round (the pile-sorting activity, which I'll explain in a future post).

The terms collected at our various sites each had some distinctive terms, making the objective of saturation problematic. The concept of saturation means that eventually additional interviews don't elicit new terms. However, by including the diaspora as part of our target group, we realized saturation was impossible, as every place that Samoans live (e.g., Samoa, American Samoa, Hawaii, New Zealand, mainland US, etc.) has a few new terms. Saturation among native Samoans in the Samoan Islands, on the other hand, was reached pretty quickly, and there was considerable overlap in the terms people provided us, as opposed to the list of terms we gave them to choose from. In Samoa we collected the "free lists" differently. My collaborators were concerned that asking Samoans to simply write down terms associated with typical Samoanness would be difficult for a number of reasons. Bernie was born in Samoa but raised in New Zealand, and she understands both the Western and the Samoan mind. She could do this method in New Zealand as I did in Hawaii but not in Samoa. Leota was born and raised in Samoa and has only traveled out of Samoa once, to visit family in New Zealand; and he agreed completely with Bernie. The issues were language and custom. For Samoans, writing is not a custom, considering they were a preliterate society until ~200 years ago. They do not see the point in writing about their culture when they live it daily. Moreover, Samoans main ethos (and this came out of our research and from Bernie and Leota) is hospitality, so they are generally eager to please. Thus, they are also likely seek to write what think researchers are looking for and not much else. Instead, we gave them a partial list of terms that typifies Samoans according to the literature from which to choose. We drew on previous research by Dr. Samau, as well as unpublished work by Leota Sanele. Both have explored similar topics in their work, making these terms theoretically and culturally relevant. We compiled a short list of terms and added several blank lines after the list. We asked participants to circle each term they identify with typical Samoanness and to write down at least six additional terms not on our list. The lists were translated by Leota and checked by Bernie, and bilingual participants indicated to us that the consent and survey made sense to them in both languages. All good stuff, right?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed