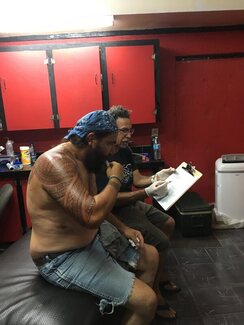

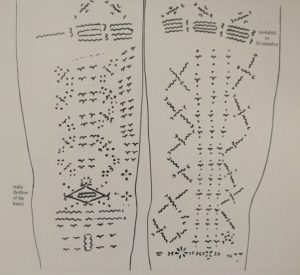

Na ou i ai i Samoa mo le masina, e sailiili i le tu o tāga tatau faaSamoa ma le aafiaga o mamanu tetele e iai le pe‘a ma le malu –poo le tatau i lona tulaga lautele –i le mafai e le tino o le tagata ona tali atu i siama. Na i‘u ina ta ai loa ma la‘u pe‘a i lo‘u vae, e ui e laitiiti mamao atu. O le vaitau lea o a‘u suesuega i nofoaga i tua, ma e atoa i ai le fa o a‘u suesuega faatino i le faiā o le tāina o le pe‘a ma le tete‘e poo le tali atu o le tino o le tagata i faama‘i poo ni siama. O la‘u sailiiliga muamua na faapitoa i se vaega to‘alaiti, e matele i tamaitai, i Alabama. O le mea na ‘ou matauina na faaataata mai ai, e mafai ona fesoasoani le taina o le pe‘a e siitia ai le mafai ona tete‘e pe le tali atu i inifeti ma siama. Ae lē lava se suesuega itiiti se tasi i Amerika e faamaonia ai se o‘oo‘oga o le mataupu –e ui i ulutala matamata tetele o faasalalau solo ai le fo‘ia o le fulū masani i le tāina o le pe‘a. O le mea tonu e ta‘u o le faasaienisi maumaututū, o le maua lea o le tali lava e tasi, mai le lasi o suesuega, ona faauiga lea ia maua ai se malamala‘aga e faatatau i le lalolagi. O le mafuaaga lena na ma malaga ai ma Michaela Howells, i le matātā lava e tasi tau Su‘esu‘ega o Tagata, i motu o Samoa. E loa le talafaasolopito faifaipea o tāga tatau i Samoa. Sa faaaogā masini faaonaponei ma sa ta lima fo‘i pe‘a, ona sa matou fia iloa pe maua ai le fesootaiga lava e tasi - o le faasiliga malosi e maua e le vaega tetee siama o le tino. Lāgā le vaega tete‘e siama e puipui manu‘a iti mai le tāina o le pe‘a E silia ma le 30% o tagata Amerika e ta a latou pe‘a [e o‘o mai] i le asō. E ui i lea, e laiti suesuega na faia i ni aafiaga faapaiolo e ese mai ma lamatiaga tau kanesa poo le inifeti. O le tāina o le pe‘a e gaosia ai se ata tumau pe a o‘o le lama (vaitusi) i pu iti ua taina i lalo ifo o le vaega pitoaluga o le p ‘u. E manatu lou tino o se manu‘a le pe‘a ma e faapenā ona tali atu i ai i ni auala se lua. O le gaoioiga faanatura a le tino e teena ai se faamai poo se inifeti, e aofia ai le tali masani i soo se mea fou e alia‘e. O le mea lea, o le tāina o le pe‘a, e faaosofia ai le vaega tetee faama‘i e ‘auina atu ni sele papa‘e o le toto e ‘aina le ‘au osofa‘i, ma tete‘e atu i ai tusa pe mamate ai (sele papa‘e), a ia puipuia le tagata mai le inifeti. O le mafai e le vaega teesiama o le tino ona ola fetuunai, na maua ai le avanoa e fua ai le porotini imunekelopulini e maua i le fāua, ‘auā se ata faatusatusa o le tūgā e o‘o i ai pe a ta se pe‘a. I Amerika Samoa, na ma galulue ma Howells i le ofisa Faasao o Talafaasolopito e saili ni tagata e faatino ai le suesuega, ma sa fesoasoani mai atisi ta pe‘a ia Joe Ioane mai le Off Da Rock Tattoos, Duffy Hudson mai le Tatau Manaia, ma le tufuga ta tatau ia Su‘a Tupuola Uilisone Fitiao. O tagata e to‘aluasefululima na lautogia mo le tāgā pe’a e aofia ai tagatanuu o Samoa ma turisi asiasi mai.  Chris Lynn na aoina faamaumauga i nei i Amerika Samoa. Michaela Howells, CC BY-ND Chris Lynn na aoina faamaumauga i nei i Amerika Samoa. Michaela Howells, CC BY-ND Na matou aoina faamaumauga o fāua i le amataga ma le faai‘uga o tāgā pe‘a ta‘itasi, ma faapito‘augafa suesuega na ‘o le taimi na tatā ai. Na matou fuaina fo‘i le mamafa, le ‘u‘ūmi ma le māfiafia o le ga‘o i tino o le ‘au tatā, e iloa ai le tulaga o lo latou soifua mālōlōina. Mai su‘esu‘ega o le fāua, na matou tō ‘ese mai ai le vaega tetee faama‘i A, le homoni e tutupu mai ai faalogona o le lē to‘a, atoa ai ma le porōtini-C lea e faailo mai ai ua lūgā se manu‘a. O le vaega tete‘e faama‘i A ua faatusa nei o le ulua‘i talipupuni tāua, e puipuia le tagata mai siama e pei o ituaiga e maua i le fulū masani. O le faatusatusaga o tulaga o nei faailoilo tau paiolo, na matou mautinoa ai le maualuga o le vaega tetee faama‘i A i totonu o ālātoto, e o‘o lava ina ua pepē manu‘a o le pe‘a. E lē gata i lea, o i latou ua faatele ona tofo i le au o tāgā pe‘a, na tele le porotini (Imunekelopulini) tete‘e siama na maua i o latou fāua, e faaata mai ai le siitia o le malosi teesiama mo ē ua toe ta, e faatusatusa ia i latou ua faato‘ā tatā ma e le‘i o‘o lava i lea faiva. O lea aafiaga e faalagolago i le ta so‘o o le tino, ae lē na ‘o se vaitau ua mavae talu ona ta. E ono aogā lea malosi faasili mo le vaega teesiama ‘aua nisi manu‘a o le pa‘u e alia‘e mai, atoa ma le soifua mālōlōina lautele. E foliga mai a ta le pe‘a, e mafai ona aogā lea mo le tino o le tagata. O se molimau lena mai le ‘au suesue i le matātā faapaiolo, pe a faailoa tonu sele tetee faama‘i i molekiule e fitoitonu i ai, ona aga‘i sa‘o lea i pōlōtini magalua ia e faamautū pea i totonu o ālātoto o le tagata i le tele o tausaga. O taimi uma e ta ai se pe‘a o le taimi fo‘i lena o loo tapena lelei ai le tino e tali fuaitau atu i se isi tāgā pe‘a e soso‘o ai. Na māua i isi suesuega le aogā o le lē to‘a (o le tagata) mo sina vaitau puupuu, ma e penefiti ai fo‘i le vaega tetee faama‘i o le tino. O le ituaiga faalēlelei, o le ituaiga lē to‘a lea e matuā olopalaina ai le vaega teesiama ma le soifua mālōlōina o se tagata. Peita‘i e aogā sina lē to‘a ititi aua e tapena ai lou tino e tetee atu i siama. E aogā faamalositino masani mo vaega tetee faama‘i o le tino pe ‘a fai ma masani, ae lē na ‘o aso ta‘itasi e asi ai se fale toleni. Matou te manatu, e tai tutusa lea ma le tapenaina e le tatau o le tino, ina ia mātaala mo soo se faafitauli e ono tula‘i mai. Na lagolagoina e faaiuga i Samoa a matou ulua‘i suesuega i Alabama. Ae lē faapea a felāta‘i ona faailo mai ai lea o ‘i‘ina le mafuaga tonu. E moni e felāta‘i le ta faafia o le tino o le tagata, ma le siitia o le malosi o le vaega tetee faama‘i o le tino, ae atonu o tagata e mālōlōina atu, e pepē gofie o latou manu‘a mai le taina o pe‘a, ma latou fiafia fo‘i e ta soo o latou tino. E faapefea ona tatou iloa ma le toto‘a o le ta so‘o o pe‘a i le tino e mafai ona mālōlōina atili ai se tagata? ‘O Samoa e ana le Tatau’ E i a Samoa le aganuu ta pe‘a pito i matua o loo faaauau pea i totonu o motu o le Pasefika. E ui e toatele tagata Samoa e faitio i le ta o tatau a le tupulaga ona o tifiga, ae mo le toatele o ia tupulaga, e mafua ona o le faaaloalo i o latou tupuaga ma na latou ta‘ua e faapea, o a latou tatau o se mea totino o le aganuu Samoa.  E masani ona sailia le faatagāga a aiga pe afai e fia ta se pe‘a poo se malu. O le taina ma le la‘eiina o le tatau e aofia ai le tele o tiute tau‘ave, ma e faailoa mai ai le agaga malie e fai le faiva o le tautua i nuu ma alālafaga. O nisi o tagata Samoa na auai i le sailiiliga, sa faailoa lo latou lē manana‘o i isi ituaiga pe‘a, o se tasi fo‘i o sui na ta‘ua lona fefe tele i nila. Na ta a latou pe‘a ona o le tāua o nei tatau ma malu i o latou faasinomaga faaleaganuu, ae le ‘ona o le fia faaalialia. O lagona masani o le lautele o Samoa i le mafuaaga e ta ai se tatau a se tagata, e lē mafuli ona o le fia fai tifiga, e faatusatusa i le taina o se pe‘a i le Iunaite Setete. O le mafuaaga lea ua avea ai Samoa ma nofoaga sili e saili i ai, pe mafua le faasiliga malosi e maua e teesiama o le tino, ona e mālōlōina lava tagata o loo tatā -i Samoa, soo se ituaiga tino ma soo se tagata e ta, mai faifeau e o ‘o i sui o le mālō. Ia Iulai 2019, sa aga‘i tonu suesuega eseese faapaiolo na ao, i tagata na matuā fato‘ato‘a le taina ‘o o latou tino i Apia, e pei ona faatinoina i aso taitasi i le ogatotonu o le taulaga. E 50 vaega mo suesuega o fāua na ‘ou aoina mai tagata ‘auai e to‘asefululua, ma o le a auiliili e le tagata suesue i lea matātā faapitoa ia Michael Muehlenbein, i le tausaga a sau. O vaaiga eseese i le malaga a le pe‘a E mafai ona avea le pe‘a ma pine faamau vaaia e ‘a‘apa i ai tagata e faailoga ai uo mālōlōina poo ni uo tino malolosi. O ia faailo o le lava toleni o ia tagata, ua faatusa i fusi o fulu (matagofie) o le si‘usi‘u o le manulele iloga o le tuki, lea semanū e fai ma avega mamafa pe ana le malosi ma gafatia lava e lea manu ona sola ese mai ona fili. E oʻo lava i le siosiomaga faʻaonapo nei ma le aga'i i luma o le tausiga o le soifua mālōlōina, e ono siitia e le pe’a le malosi teesiama o le tino, e ala i le faafoliga mai ua manu’a le tino, ina ia faaalitino mai ai o loo mālōlōina. I se suʻesuʻega na ou faia i le lata i le 7,000 tagata aooga o faailoga amata, o tama afeleti mai kolisi ma iunivesite eseese, atoa ai ma tama ta‘a‘alo lakapi (Amerika), o i latou ia na tele ina ta a latou pe‘a nai lo e lē ta’aalo, ma o ia fo’i alii sa tau lē aafia i ni ma’i e afua mai le taina o se pe‘a, e faatusatusa i a i latou na ta a latou pe‘a ae le ta‘a‘alo. E le ‘o manino mai le lava o penefiti e maua mai le taina o se pe‘a, ina ia iai sona aafiaga iloga i le soifua mālōlōina, o le mea lea, vaai oe ne‘i e manatu e faaleaogā e le taina o se pe‘a fou lou tausami i peka-sisi ma pateta falai. E ui i lea, e lē fesiligia o le taina o le pe‘a, e feso‘otai ma le malosi (e gafatia ai fitā), e lē gata i lena, o tatou, tagata ola, e mafai ona aafia i tatou i le vaai ma mafaufauga e pei lava o le mea moni. https://theconversation.com/untangling-tattoos-influence-on-immune-response-121852

0 Comments

Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. PrologueInstead of syllabus day, I read this story on the first day of my Fall 2017 Neuroanthropology class then launched right into the class. I’d never done this before, but I like to think of the course as interdisciplinary and experimental and that different ways of experiencing materials is important. I was inspired to do this by anthropologist Katie Hinde, who wrote a story to start her human evolution course at Arizona State and blogged about it. Katie is a friend and colleague of mine. She is a contemporary but probably a few years younger than me. Nonetheless, she is trailblazer and someone I admire and look to for inspiration in how to conduct an anthropological career-life. You can find her work at MammalsSuck...Milk, a clever play on words, as her research focus is about mammal milk. This piece is about the fieldwork I’ve conducted the past two summers. I just wrote it the weekend before the first day of class, so, for better or worse, students heard an early draft of this story that may get published on its own somewhere or in a book some day in some form that will probably ultimately be very different than this. I wrote it because I think our work this summer epitomizes the nature of neuroanthropology as essentially biocultural, and because I think this story encapsulates much of our experience of fieldwork this summer. There may be less neuro than you’d expect here, given the course I read it to, but it’s the ethnographic prelude before we’ve finished collecting and analyzing the neuro data.

|

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed