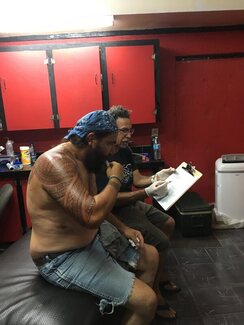

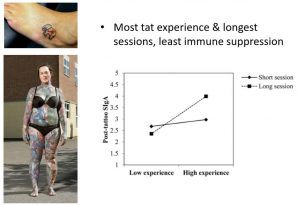

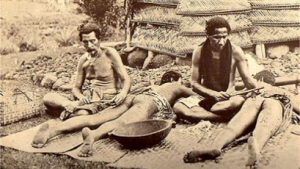

I’d been in Samoa for a month, studying Samoan tattooing culture and the impact of the big traditional pieces called pe’a and malu – tatau in general – on the immune system. Now I was getting my own hand-tapped leg tattoo, albeit considerably smaller. This field season was the fourth of my research on the relationship between tattooing and immune response. My first study had focused on a small sample, mostly women, in Alabama. What I’d observed among that group suggested that tattooing could help beef up one’s immune response. But one small study in the United States wasn’t proof of anything – despite headlines blaring that tattoos could cure the common cold. Good science means finding the same results multiple times and then interpreting them to understand something about the world. That’s why I traveled in 2018 with fellow anthropologist Michaela Howells to the Samoan Islands. Samoans have a long, continuous history of extensive tattooing. Working with contemporary machine and hand-tap tattooists in American Samoa, we wanted to see if we’d find the same link to enhanced immune response.  Chris Lynn collecting data in American Samoa. Michaela Howells, CC BY-ND Chris Lynn collecting data in American Samoa. Michaela Howells, CC BY-ND Immune defenders rush to tattoo’s tiny wounds More than 30% of Americans are tattooed today. Yet, few studies have focused on the biological impact beyond risks of cancer or infection. Tattooing creates a permanent image by inserting ink into tiny punctures under the topmost layer of skin. Your body interprets a new tattoo as a wound and responds accordingly, in two general ways. Innate immune responses involve general reactions to foreign material. So getting a new tattoo triggers your immune system to send white blood cells called macrophages to eat invaders and sacrifice themselves to protect against infection. Your body also launches what immunologists call adaptive responses. Proteins in the blood will try to fight and disable specific invaders that they recognize as problems. There are several classes of these proteins – called antibodies or immunoglobulins – and they continue to circulate in the bloodstream, on the lookout lest that same invader is encountered again. They’re at the ready to quickly launch an immune response the next time around. Your body also launches what immunologists call adaptive responses. Proteins in the blood will try to fight and disable specific invaders that they recognize as problems. There are several classes of these proteins – called antibodies or immunoglobulins – and they continue to circulate in the bloodstream, on the lookout lest that same invader is encountered again. They’re at the ready to quickly launch an immune response the next time around. This adaptive capacity of the immune system means that we could measure immunoglobulins in saliva as approximations of previous stress caused by tattooing. In American Samoa, Howells and I worked at the Historic Preservation Office to recruit study participants with help from tattoo artists Joe Ioane of Off Da Rock Tattoos, Duffy Hudson of Tatau Manaia and traditional hand-tap tattooist Su'a Tupuola Uilisone Fitiao. Our sample of 25 tattoo recipients included both Samoans and tourists to the island. We collected saliva at the start and end of each tattoo session, controlling for the tattoo duration. We also measured recipients’ weight, height and fat density to account for health. From the saliva samples, we extracted the antibody immunoglobulin A, as well as the stress hormone cortisol and inflammatory marker C-reactive protein. Immunoglobulin A is considered a frontline immune defense and provides important protections against frequent pathogens like those of the common cold. By comparing the levels of these biological markers, we determined that immunoglobulin A remains higher in the bloodstream even after tattoos heal. Furthermore, people with more time under the tattoo needle produced more salivary immunoglobulin A, suggesting an enhanced immune response to receiving a new tattoo compared to those with less or no tattoo experience. This effect appears to be dependent on receiving multiple tattoos, not just time passed since receiving one. This immune boost may be beneficial in the case of other skin injuries and for health in general. Tattooing seems to exert a priming effect: That’s what biologists call it when naive immune cells are exposed to their specific antigen and differentiate into antibodies that remain in the bloodstream for many years. Each tattoo prepares the body to respond to the next. Other studies find that short-term stress benefits the immune system. Stress’s bad rap comes from chronic forms that really do undermine immune response and health. But a little bit is actually good for you and prepares your body to fight off germs. Regular exercise provides immune function benefits through repetition, not necessarily single visits to the gym. We think this is similar to how each tattoo seems to prepare the body for vigilance. Our Samoan findings supported the results of my first study in Alabama. But of course correlation does not imply causation. Enhanced immune response is correlated with more tattoo experience, but maybe healthier people heal easily from tattooing and like to get them more. How could we find out if getting tattoos could actually make a person healthier? ‘Tatau belongs to Samoa’ Samoans have the oldest continuous tattoo culture in the Pacific Islands. Though many Samoans complain that young people are getting tatau for fashion, most get them to honor their heritage, saying their tattoo belongs not to them but to Samoan culture.  Samoans usually obtain permission from family to receive pe'a and malu. Getting and wearing these tattoos involve many responsibilities and indicate willingness to serve one’s community. Several of the Samoans in our sample had little interest in getting other tattoos, and one even reported being afraid of needles. They get pe'a and malu for the importance of these tattoos to their cultural identity, not because they are fashionable ways to show off. The social expectations for Samoans mean that getting pe'a or malu is less about self-motivated fashion choices than getting a tattoo is in the U.S. This is why Samoa is a great place to investigate whether the immune bump we see after tattooing is due to healthier people going under the needle in the first place – in Samoa people of all body types and walks of life get them, from priests to politicans. In July 2019 I focused on collecting multiple biological samples from people getting intensive tattoos in Apia, where they are administered daily in the center of town. I collected around 50 saliva samples from a dozen participants that will be analyzed in the coming year by anthropological immunologist Michael Muehlenbein. An evolutionary take on tattoos Tattoos may provide visual evidence that others home in on to identify healthy mates or hardy friends. Such signals of fitness have been compared to peacock tail feathers, which would be too much of a burden if the peacock were not have enough to escape predators. Even in the modern environment with improved health care, tattoos may “up the ante” by artificially injuring the body to demonstrate health. In a study I conducted among nearly 7,000 undergraduates, male intercollegiate athletes in general and football players in particular were more likely to be tattooed than non-athletes and less likely to suffer tattoo-related medical problems than those non-athletes who were tattooed. It’s not clear that the benefits tattooing provides are big enough to make a clinical difference on health, so don’t expect a new tattoo to cancel out a diet of cheeseburgers and fries. But there is no doubt that tattooing is associated with toughness, and that we humans influence each other through impressions as much as reality.

0 Comments

We're a little behind in our updates, so a few of these are dated...but without further ado.

This summer we ran a successful crowdfunding effort to fund the first half of a second field season to study Polynesian tattooing and immune response. I attended the Northwest Tatau Festival in Seattle/Tacoma, WA, where we collected data from 52 participants. Next step is to gather the funds to analyze the samples!

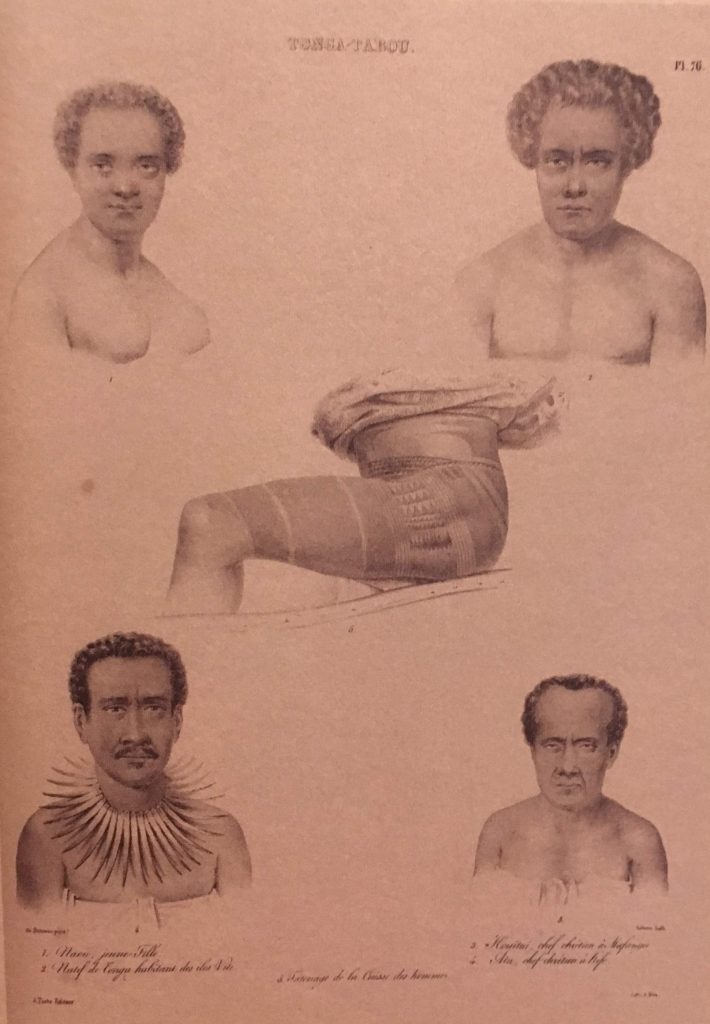

Oh, they tried. According to Mallon and Galliot, the decentralization of Sāmoan authority may have played a large role and been abetted by the later arrival of the missionaries in the Sāmoan archipelago than to other islands. The initial missionization of Sāmoa was conducted by John Williams and the London Missionary Society, which had gone first to Tonga. Tonga and the Sāmoan Islands are close and have a long (and tense) history of close interaction (this according to a book I picked up published by the Samoan Studies Institute of the American Samoa Community College that I will have to track back down to cite appropriately). Thus, there have always been lots of Sāmoans in Tonga and lots of Tongans in Sāmoa (with the requisite slanders against each other--see my previous post for a bit on this in my field experience). In Tonga, they met a Sāmoan who had already converted to Christianity (not sure how, but there were vagabonds, outlaws, and castaway Europeans who had arrived in the Sāmoas earlier and set up heretical little Christian cults for themselves before) and who became their emissary and assistant in Sāmoan Christianization (this is my memory from reading Robert Shaffer’s coffee table history, American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag) while sitting in Off Da Rock Tattoos waiting for Joe to finish tattooing so I could collect another saliva sample).  Drawing of Tongan tatatau by Louis Auguste de Sainson, official draughtsman of the voyage of Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumon d'Urville 1826-1829 on the corvette Astrolabe (From Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 31)[/caption] Drawing of Tongan tatatau by Louis Auguste de Sainson, official draughtsman of the voyage of Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumon d'Urville 1826-1829 on the corvette Astrolabe (From Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 31)[/caption]

Importantly, early European reports of South Pacific tatau have it that Sāmoan and Tonga styles were similar or the same and characterized mostly by description of the pe’a, the male tatau the looks like nearly solid blue shorts. But Tonga was centralized under King George Taufa’aahau, who was Christianized by 1831 and banned tattooing in 1839 in the Vava’u Code, Tonga’s first set of laws. This effectively ended “traditional” tattooing as practiced by Tongans, but this did not apparently stop the Tongans from getting tatau—they simply traveled to Sāmoa for them! The same was true in other Pacific Islands. Makiko Kuwuhara indicates that tatau had disappeared in Tahiti shortly after the arrival of missionaries in the early 1800s in Tattoo: An Anthropology, and Tricia Allen notes the same pattern for Hawai’i in Tattoo Traditions of Hawaii. According to Mallon and Galliot:

Part of the issue was that not enough missionaries were in the Sāmoas to have the kind of impact they’d had on other islands without the help of a central native authority. A previous Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS) mission had made a small number of converts, but the mission was ended early because John Williams of the London Missionary Society (LMS) convinced the Wesleyan London HQ that the two missions (WMMS and LMS) had agreed to give LMS free reign over the Sāmoas. WMMS didn’t return until around 1857 and seems to have been somewhat indifferent to tatau. Reports about missionary indifference to tatau are ambivalent though—the issue seems to be that missionaries were aware of their limited numbers, precarious support, and potential for backlash if they were too heavy-handed in banning everything Sāmoans liked about their own culture. Tufuga tā tatau (tattoo master craftsmen) were considered matai (chiefs) and garnered high rank, status, prestige, and honor. Tatau ceremonies were huge village expenses lasting weeks to months that bonded alliances together. For instance, German colonial efforts to limit the authority of matai is what led in part to Sāmoan colonial resistance and forging allegiances with the U.S. and British to push the Germans out.  Auta collected before 1871 and now in the British Museum collection (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 43). Auta collected before 1871 and now in the British Museum collection (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 43).

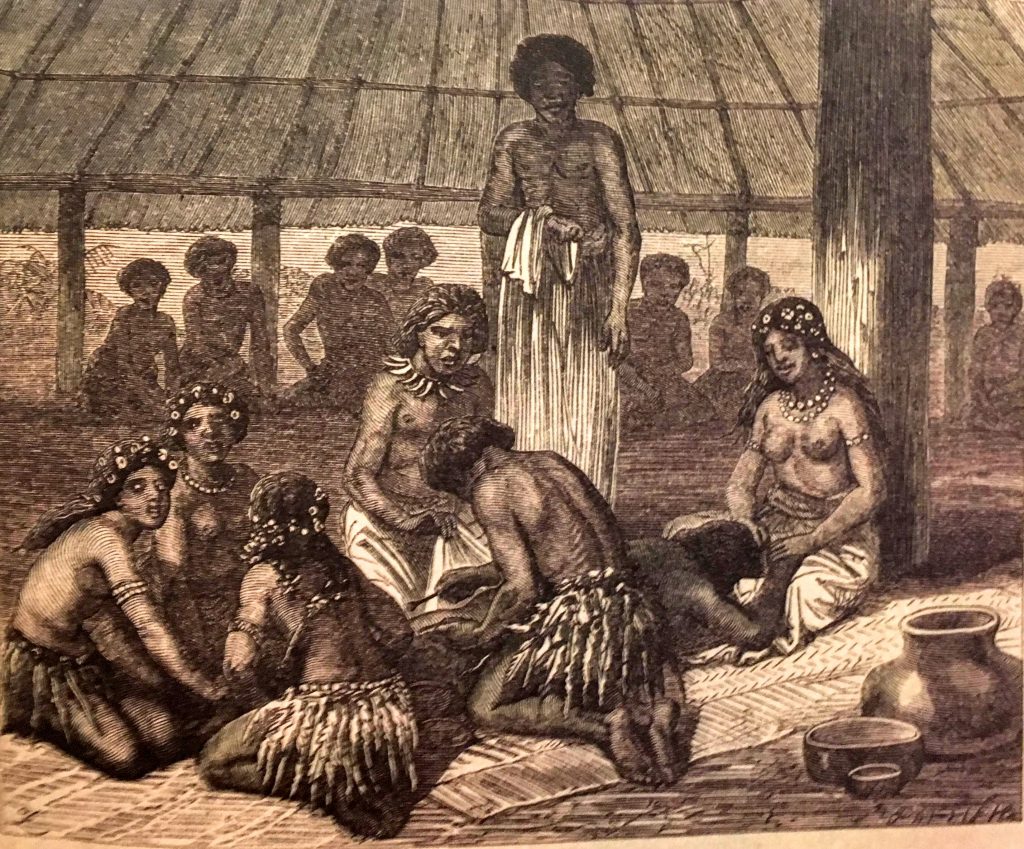

Sāmoan culture may have also benefited in ways from a period in which several matai were struggling to attain dominance over others but not succeeding. Part of Williams’ LMS missionization strategy in the Sāmoas was to convert chiefs who would impose Christianity in their territories. Not long after he arrived in 1830, he converted powerful chiefs Mālietoa Vaiinupō and Tui Ā’ana Tamalelagi, who made it possible to establish long-term missions in several districts. However, other districts resisted specifically because of traditional oppositions to the ‘āiga sā Mālietoa (Mālietoa clan). Williams realized he couldn’t institute laws without backlash by the powerful opponents and thus trained his missionaries to apply a light hand, making themselves available to give advice and so practice a more subtle form of evangelizing. Thus, Sāmoans were able to pick and choose what aspects of Christianity they wanted to abide by and which they did not. The ability of some matai and their villages to hold out—and, ironically, an extended period of civil war among Sāmoans in the 18th century—may have protected much of Sāmoa’s cultural traditions, including tatau, from being relegated to the wastebin of the Christian missionization. Many districts on the big islands of Upolu and Savai’i remained untouched by LMS even 30 years after Williams’ arrival. Not far from where John Williams first landed in Savai’i, for instance, Chief Su’a of Salelāvalu remained faithful to native beliefs and maintained the last temple shrine in Sāmoa, a temple of Taimā (Taemā and Tilafigā are the twin women fabled to have brought tatau tools to Sāmoa and gifted them to ‘āiga sā Su’a).  Tattooing day in Samoa 1868-70. Illustration for a publication titled 'The Natural History of Man: Being an Account of the Manners and Customs of the Uncivilized Races of Men' (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 49) Tattooing day in Samoa 1868-70. Illustration for a publication titled 'The Natural History of Man: Being an Account of the Manners and Customs of the Uncivilized Races of Men' (from Mallon & Galliot 2018, p. 49)

Despite how über-Christian Sāmoans are today, their adoption of Christianity was reportedly very strategic. Missionaries arrived with cool swag (metal stuff, linen cloth by all accounts was just way more comfortable on the loins than siapo bark cloth—go figure), and chiefs could obtain prestige in their communities by allying with them. But the missionary period coincides with a struggle for the four pāpā—the four supreme titles of the Sāmoan hierarchy that comprised several large alliances—to become Tafa’ifa or sovereign over Sāmoa. The previous tyrannical Tata’ifa has literally just been offed by villagers from Fasito’outa weeks before Williams arrived. Thus Williams was faced with converting chiefs who were in the process of consolidating power for their own purposes. Thus, they would promise to obey Christian rules not to kill thy neighbor…right after they killed all those SOBs in the districts that opposed them. Ultimately, Sāmoans chiefs allied with various missions and colonial powers in attempts to attain hegemony in the archipelago, but no one power ever actually succeeded. Since there is little record or description of Sāmoan tattooing before the colonial and missionary period, it is unclear how much tattooing changed. It appears to have varied throughout the islands, consistent with the prehistory of political instability across not just the Sāmoan Islands but also in conjunction with the extended relationship with Tonga. An ethnographic account by German naturalist Augustin Krämer (probably largely co-authored by Sāmoan chief Tofā Sauni), who worked in Sāmoa from 1897-99, suggests that the missionary impact on tattooing was that it transformed from being a large public ceremony to being a private one. The political system of Sāmoas remained largely intact; thus, tattooing was preserved in Sāmoa. Some of the larger changes in how Christianity appears so ubiquitous today in Sāmoa would come later with the arrival of the Mormons, Seventh-Day Adventists, and Pentecostals; but, while some of these continued to ban tattooing, some of the staunchest defenders of tatau today are among Sāmoan Christian pastors. More on that in a future post as I continue to explore this amazing book! I am excited by the prospects of returning to the field next summer to do more research, as I’ve been digging into relevant theory in cultural evolution that is, I believe, spot-on in outlining what is going on with the resurgence of Pacific tattoo cultures. I’m struck by how completely so-called traditional tattooing practices were quickly purged from many Pacific cultures in the 19th century. (I use the term “traditional” as shorthand, since Pacific cultures have maintained tattooing practices to varying degrees during this period and never been isolated from the influences of each other or outsiders—according to Samoan poet and activist Albert Wendt, as quoted by anthropologist and Te Papa Museum Senior Curator of Pacific Cultures Sean Mallon in “Against Tradition”—there is no such thing as “traditional.”) Mind you, we all know what shits missionaries and colonial agents were in trashing native cultures, but it wasn’t one-size-fits-all trashing. For instance, the French were more interested in trade alliances than enforcing decorum, such that it appears many French colonials got tatted up in native styles to show their sincerity (e.g., Bienville). It’s like when our ALLELE guest speakers throw out a gratuitous “Roll Tide” at the beginning of their talks to ingratiate themselves with the audience, except, well, way more committed to their cause (I wonder if LSU ichthyologist Prosanta Chakrabarty will say “Roll Tide” this week when he gives his talk two days before Bama whips LSU’s patootie…). https://twitter.com/PREAUX_FISH/status/1055465915033247744 I’m a few chapters into reading Makiko Kuwuhara’s 2005 ethnography on tattooing in Tahiti (efficiently titled Tattoo: An Anthropology), and she notes that Tahitian tattooing almost completely disappeared right out of the missionary gate in the early 19th century (perhaps why we don’t see any tats in any of those Gaugin paintings). Tahitian tattooing reappeared like it did in the mainland U.S., among fringe and “deviant” types and in similar motifs. Then, what is so fascinating to me, traditional tattooing was reintroduced by Samoan tufuga ta tatau (tattoo masters). I am imagining the Samoan tufuga who reintroduced traditional tattooing to Tahiti was the Sa Su’a Sulu’ape guild, but I haven’t read far enough in to confirm. However, based on our ethnographic interviews with tatau historian Christian Ausage in 2017, the Sulu’ape branch of the Sa Su’a guild was all that remained and that persisted of traditional Samoan tattooing. Sulu’apes have, as far as we can tell, ensured that the Samoan tradition remained unbroken and taught all active Samoan tufuga today. At least this is one of the things we’ll be investigating. Some of these answers are no doubt in the new book by Sean Mallon and Sébastien Galliot, but I have yet to get my hands on a copy.  Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author). Su'a Petelo Sulu'ape sharing knowledge with our student research assistants before the Northwest Tatau Festival, Puyallup, WA, 2018 (Photo by author).

I am imagining that a variety of environmental/social factors are at play here, which, in theory, we can mathematically demonstrate with the data in hand. Joe Henrich, Bob Boyd, Pete Richerson, Christopher von Lueden, Alex Mesoudi, Maciej Chudek, and others I’ve been reading over the past few weeks make the case and provide the models we can use to test a few predictions in this regard. Robert Shaffer’s giant coffee table book American Sāmoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag indicates that tattooing and other native practices were banned by missionaries in Samoa but that Samoans just tended to compartmentalize and ignore some of those dictates, while becoming über Christian. Some have derisively called Shaffer’s history a biased account of governmental propaganda, but he was good friends with several Samoans I’ve come to respect immensely, such as Reggie Meredith and Wilson Fitiao, so I don't dismiss it out of hand. The book essentially indicates that, in the mid-19th century, American Samoa asked to become a territory of the U.S. so German mercantile companies did not take them over as was happening with Western Samoa. According to the book, Germans came into Western, set up trade, took land from native peoples, made tons of money, were pricks, and that led to the infamous standoff between British, U.S., and German navy ships that was interrupted by a hurricane (the summary of most brief histories of American Samoa). The colonial powers then simply divided the Samoas up instead of fighting over them, with Western Samoa going to Germany, Eastern going to the U.S., and the U.S. giving Britain Guam. After WWI, New Zealand was gifted Western, which became independent in the 1950s. After that, a quote from former American Samoa Historic Preservation director John Enright from his noir detective series (Fire Knife Dancing, in this case) based in American Samoa seems aptly to describe the circumstances, though it also brings into question the whole please-help-us-U.S. of Shaffer:

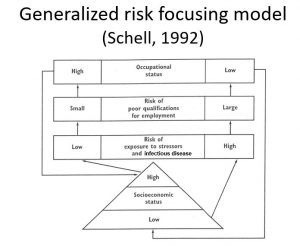

But I digress. The simplifying model I’m imagining (great quote from someone via Katie Hinde during her recent visit by the way—“all models are simple; some are useful”) is that:

Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption] Several members of a Hawaiian MC were in the house getting their Pacific tatau (Photo by author, Northwest Tatau Festival, July 2018).[/caption]

Among the sources I know I’ll be returning to again and again as I explore this, Joseph Henrich “Cultural Transmission and the Diffusion of Innovations: Adoption Dynamics Indicate That Biased Cultural Transmission Is the Predominate Force in Behavioral Change.” I think everything we need to know right now is right there in that title. [Nerd drops mic] One of the reviewers for my recent article on tattoos among undergraduate athletes turned me on to another tattoo researcher who I'd previously overlooked. Andrew Timming is an associate professor of human resource management at the University of Western Australia whose focus is the social psychology of work. Of interest to us in particular is his research on perceptions of tattooing in the workplace. How do employers/potential employers view them? How do customers view tattooed folks in businesses they patronize? I like his work because the perception of tattooing research has largely been so coarse-grained. We've been focusing on how people perceive others with tattoos---usually as open-minded people who take a lot of risks---but we all know that a lot goes into that perception and which we struggle to measure in our studies: style of tattoos, quantity, location, quality, how it fits the person, context, other stuff about the person, etc. and so on. Timming's work is digging into specific situations with ingenious nuance. Since he's interested in human resource psychology, his focus gets at a locus where a lot of these opinions and the possibility that we act on them matter. And one of his major findings is something I've been interested in my work. In "Body art as branded labour," he

His intuitively logical finding is that some employers market in hipsterism and edginess and value visible tattoos. Their employees looking cool makes them look cool. I say this seems intuitive, but maybe that's because I worked in the music industry for several years. Working in records stores and music distribution, it was people who dressed in suits or conservatively who had a more difficult time. Of course, it's not all about having tattoos or not having tattoos. What makes tattoos so important is that they are unique as a permanent commitment to style or attitude. Jack Black's attitude comes across quite clear in the movie Hi-Fidelity, but maybe it takes asking for "I Just Called to Say I Love You" to learn that (probably not, but you get my point). https://youtu.be/-ECyX8A3iP0 (Incidentally, I have acted just like this in my former life as a record store clerk. It was because I didn't like the store owner and didn't want people shopping there, but the owner saw me and didn't care. It's really a thing.) I wanted to introduce Timming's work because a new article is out that is getting a fair amount of press. Though it's sort of meta. When I search "tattoo study" on Twitter (yes, to RT my own press □), I get: https://twitter.com/guntrust/status/1053107010898681856 Which leads back to a study that was just published in August in Human Relations called "Are tattoos associated with employment and wage discrimination? Analyzing the relationships between body art and labor market outcomes" by Michael French (lead author) and Karoline Mortensen at University of Miami. They collected survey data from 1323 females (women? men? trans?) and 685 (males) via MTurk and found that

This does not suggest that tattoos are accepted in all walks of life now, but it does suggest what it means to say that tattoos have gone mainstream. The number of occupations where tattooing is now OK has crossed the cultural Rubicon (it's now cool to be a tattooed college professor---elbow patches are only cool if you're ironic or not ironic that you're 'cute'). OK, now this part gets a bit confusing. Another new article out in 2018, this time in Journal of Social Psychology, is "What do you think about ink? An examination of implicit and explicit attitudes toward tattooed individuals" by Colin Zestcott and colleagues. (This is not to be confused with "What do you think of my ink? Assessing the effects of body art on employment chances" by Timming and colleagues the year before.) Zestcott is as assistant professor of social psychology at SUNY Geneseo (note, while neither Andrew Timming, Michael French, nor Karoline Mortenson appear to be tattooed hipster doofuses like me, Zestcott is fully ironic with shirt, tie, and tattoo-sleeved forearm! □). This is a survey study using MTurk as well (40 females, 36 males---again, I self-righteously ask---it's 2018, can we use self-identified gender and not sex, if it's nuance we're looking for, as well as more accurate representation). Zestcott previously conducted a similar study of tattooed individuals with neck tattoos and found evidence for an implicit bias against people with neck tattoos even if they said they were acceptable, suggesting there are still latent negative feelings in the general public against tattoos. While tattoos may be mainstream in general, some tattoos are still not so common or accepted, including neck tattoos. But in this new study, they had folks rate 27 different tattooed people across a variety of dimensions, some of whom had neck tattoos, and took 6 that received the most average ratings to be compared compared to a variant of the Implicit Association Test. While participants expressed negative explicit and implicit biases toward tattooed individuals, those biases were not associated with strong negative emotions or disgust. This is an important point because

Cool, so I don't disgust you... □ All summer after our fieldwork for the Inking of Immunity project at the Northwest Tatau Festival (see video about our project here and follow along on Facebook here), I was asked the same two questions: did you get any tattoos at the convention? And, why are you tattooing yourself? This post is the FAQ to answer those questions, because people seem to find the answers (and the sausage that goes into the science) interesting. Did I get any tattoos at the Northwest Tatau Festival, where around 100 tattooists were working, including some of the most celebrated Polynesian and traditional tattoo artists in the world? Um, no, dammit. I wish. No, I didn’t get any tattoos at the convention because that would have meant I was spending the money folks gave me for research on personal tattoos (and one specifically said, don’t get any tattoos with this). I hoped to maybe get some work done before the convention started, but we were literally working (observing, networking, training) the whole time. The convention was two days, but the malu and pe’a Sometimes this is followed up with this question: You know all those tattoo artists and are doing this research—you don’t get any freebies? Nope, no freebies. First, we were working a convention, where many people had appointments already set up. Second, if they were tattooing me for free, they’d be passing up on paying clients. Three, if I were getting tattooed, I wouldn’t be collecting data—there was literally no time to get a tattoo while collecting data. Believe me, I would love some Poli tat work, and I would have spent donor money on it in a hot second if that’s what it Why are you tattooing yourself? My answer to this question is longer. After the last year of watching and learning about hand tapping and thinking through some of the issues underlying our study, I’ve become intrigued with the mechanics of tattooing, not just the biological mechanisms of the immune response (Do different techniques affect immune response different? Does how much it hurts matter? Do different inks matter? A friend of mine noted the issue with carriers and immune response). While conducting the crowdsourcing campaign on Instagram, I went down a stick-and-poke or handpoke tattoo hole as well. Handpoke tattoos are fashionable at present. Many of you learn about handpoke and recognize them for their previous slang derogation—jailhouse tattoos. And, indeed, if you search handpoke tattoos or stick-and-poke tattoos on Google or Instagram or Pinterest, the aesthetic among many of the twentysomething EuroAmerican hipsters out there doing it is, get drunk with your friends, draw designs, tattoo them on each other. They tend to be small, ironic, and potentially embarrassing. However, they’re also quite popular and prominent in music culture, from Ninja of Die Antwoord to Post Malone. But when I went down the Instagram hole, I found some really amazing handpoke stuff too. It simply looks different than work done with multi-needle tattoo machines. I became interested in what could be done, the inks that were being used, how deep people were going, how it felt, and if I could understand traditional hand tapping better by tattooing myself. In other words, a little participant observation meets autoethnography. And, to me, the And of course with YouTube, we can figure out how to do almost anything nowadays (there’s a great series called AfterPrisonShow on how to make jailhouse tattoo guns and how to teach yourself to use them to become good). https://youtu.be/3qn9FcZZe7E I picked a design I like and thought I could pull off and a part of my body I didn’t care if I screwed up on. I tend to be ambitious, even when doing things for the first time and know I have a decent hand for art, so I chose an ouroboros design. I’ve always loved the symbolism of the ouroboros and feel like life—and particularly our consciousness (see the book I’m writing for more on this)—is a tension between devouring ourselves and thriving. It’s death and birth literally, it’s the cycle of the day, cycle of the year, winter vs. spring, you name it.  I chose to try to make this ouroboros design for my very first self-handpoke tattoo. I chose to try to make this ouroboros design for my very first self-handpoke tattoo.

For the first one, I started with a sewing needle taped to a pencil with a bit of thread wrapped around the end as an ink reservoir and non-toxic, water-soluble blotter ink. The ink was very thick, almost like toothpaste. I shaved the spot on my ankle, then cleaned it with alcohol on cotton balls. (Those cotton balls end up getting stringy and make a mess. The pads used to remove makeup are much better, but I discovered that later.) I bought a light blue thin tip sharpie to draw the design on, but it didn’t work. I had to revert to a regular ink pen. The trick I eventually learned is that as soon as I start wiping away extra tattoo ink to see better, I wipe away the drawing. Therefore, it’s best to get enough pokes to make an outline before wiping it all down and losing the drawing. It can be redrawn, but if you’re using a stencil and not drawing by hand or aren’t steady and accurate with your drawing, you might be in trouble—again, stuff I would figure out along the way.) Before wrapping the thread around the needle, I sanitized the needle with the flame from a lighter, then cleaned it with alcohol.  My first handpoke kit. Note: There's a reason tattoo artists use those little plastic caps to put ink in and stick them in petroleum jelly. This lid is way too big to use to dip, and it moves around too much without something to stick it in place. My first handpoke kit. Note: There's a reason tattoo artists use those little plastic caps to put ink in and stick them in petroleum jelly. This lid is way too big to use to dip, and it moves around too much without something to stick it in place.

That first night, I could not get much of the pasty ink to go in. It was too thick and didn’t flow well, so I accomplished an outline of my design, but it was a raw red outline of punctures. The punctures were not deep and not exactly bleeding, as I was tattooing my inner ankle, and only going about 1-2 millimeters deep, but that spot is apparently very sensitive, and it hurt so bad after an hour or so that I had to stop for the night. This problem led me to wonder what carriers are and why people had mentioned that. So I investigated, and it turns out there is pigment, which varies in density and brilliance, and there are carriers, which hold the pigment and interact with your skin. For instance, alcohol is a good carrier because it moves into skin. And it’s antibacterial. If you watch tattoo artists set up, many will squirt a little alcohol or alcohol-based soap into their ink to get the viscosity they want. So then next night, I played with that, which worked much better. I also tried working with two needles. Most tattooing is done either with machines using various needle configurations to cover more skin faster or various head lengths when hand tapping. I put two sewing needles close together to see if I could speed up this process and make heavier outlines. However, the sewing needles aren’t thin enough to do this well, and I toggled back to the single needle after a time. Also, I don’t think my blotter ink had much pigment, because I had to keep going back over and over the same areas to get enough ink in for the design to show. I did this again until it hurt so bad I couldn’t stand it anymore.  I tried a couple different configurations with the sewing needles, playing with different diameter needles and doubling needles. I tried a couple different configurations with the sewing needles, playing with different diameter needles and doubling needles.

Many hand tappers simply use tattoo needles and tattoo ink, since they are so cheap and readily available on the internet. So I decided to wait till it healed up and go over it again with tattoo ink. And, indeed, I found a bottle of black and a box of 20 sanitized individual needles for $6 each ppd on eBay.  First handpoke effort, using sewing needles and blotter ink.[/caption] First handpoke effort, using sewing needles and blotter ink.[/caption]

Now, in the meantime, all the data collection I’ve already written about happened. Let me recap some of what I've written about over on our crowdfunding site, at least the part relevant here. After the 2nd day in Seattle/Tacoma, I believe, of watching Su’a Petelo Sulu’ape (affectionately known by the tatau community as “The Old Man”) administer malu, Mua of Paka Polynesian Tattoo, the shop hosting Su’a Petelo and his son Su’a Paul Sulu’ape, told me to go out and chat with the Old Man. “He’s been drinking so he’s in storytelling mood. Go have a drink with him.” (Also, as later would become apparent, the Old Man is a high-ranking matai, or chief, and, really, probably equivalent if not literally the Paramount or high Chief of the tatau community, so everyone is expected without needing to be told to go pay their respects to him—this was a way of telling me to pay my respects). It was just me and the Old Man outside the shop, and I asked him about the tool innovations Su’a Peter (another of his tufuga or master artisan sons) had told me about the previous year. The Old Man reiterated the stories of those innovations in great detail. Then I asked him about his inks, since I know Intenz has branded an ink in his honor called Suluape Black. He said the Intenz guys marketed that ink with his blessing based on his ink formula, which he developed personally. He told me about the formula he and his brothers were using to make ink and the secret change he personally had made to get a darker black. I commiserated that I’d played with blotter ink and alcohol to try to understand the issues he’d been facing and showed him my ankle tattoo. This is what got me thinking more about the importance of pigment and what specifically is used as the carrier and how some carriers may dilute or dull pigments more than others or cause them to seep out into the surrounding skin (for instance, I’ve noticed that using alcohol to wipe mine down seems to facilitate the ink to spread out over a broader area, so that there appears to be a grey shadow around my tattoos where the ink has bled beyond the boundaries of the tattoos themselves).  Stick-n-poke kit #1 (left) and kit #2 (right). Stick-n-poke kit #1 (left) and kit #2 (right).

After fieldwork, I went back to experimenting on myself. Long story short, the tattoo needles and tattoo ink work way better. The ink is darker and more fluid, so I can tattoo faster and darker with it. The tattoo needles are also much thinner and sharper, so it hurts less and penetrates better. I completely redid the ouroboros tattoo, then, because the needles was so much finer, it enabled me to have the precision to add some detail work that required a fine hand. The most difficult part was building up thick outlines  Re-done ouroboros tattoo with a bit of my revised kit above. I sketch with the yellow sharpie, then go over it with the green to get the lines right and ensure I can see them. Re-done ouroboros tattoo with a bit of my revised kit above. I sketch with the yellow sharpie, then go over it with the green to get the lines right and ensure I can see them.

For years I’ve wanted a rooster and a fish on my knees. My rule of thumb (which I’m violating literally left and right [both my legs, get it?] lately). When my wife and I were trying to have our kids, I was in a painting phase where I was using acrylics and painting designs on our furniture (e.g., filing cabinets). I painted several with magical symbols of fertility I found in a coffee table book of cross-cultural magical icons. I painted three roosters and three fish, and we ended up with three babies. (Maybe I painted them during the pregnancy, knowing I had three on the way—I don’t recall. My point is that these were important to me and have remained so.) Therefore, my next tattoos were a rooster on the inside of my left knee (it’s easier to reach the inside when one is tattooing oneself, and it’s less subject to distortion when flexing) and a fish on the inside of my right. Most handpoke tattoos tend to be small, but as I noted previously, I tend to be ambitious and enjoy the detail work, so they both ended up larger than first intended. However, I like them, so why not?

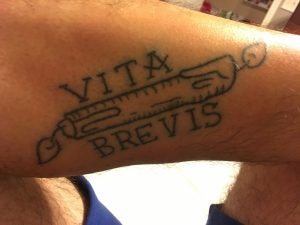

The last one I’ve done to date is something I picked from handpoke flash on the internet. I used to hate flash as unoriginal, but through my research I came to appreciate the Americana style like old Sailor Jerry stuff, and of course Sailor Jerry has become one of the markers of the rock’n’roll, punk, rockabilly, greaser, gearhead, Rat Fink, tattoo subculture I’ve identified with throughout much of my life. So the last one I share with you is “vita brevis,” which I placed on my inner left calf. Vita brevis means “life is short,” and it’s a candle burning at both ends. The full quote, attributed to Hippocrates, is “ars long, vita brevis” or “art is long, life is short,” and perhaps I’ll do an art is long tat on the other calf, but school has started back up and I’m back in Alabama with a thousand other projects calling to me and saliva samples from the field season to get analyzed, so who knows when that will happen.  (Art is long, but) life is short. (Art is long, but) life is short.

One funny thing that won’t happen is that several of my students have seen my tats (handpoke is popular, I’m telling you, so many have them) and not only asked me to tattoo them but offered to pay me to do it. Not. Gonna. Happen.  UA Anthropology graduate student Mackenzie Manns (Photo courtesy M. Manns).[/caption] UA Anthropology graduate student Mackenzie Manns (Photo courtesy M. Manns).[/caption]

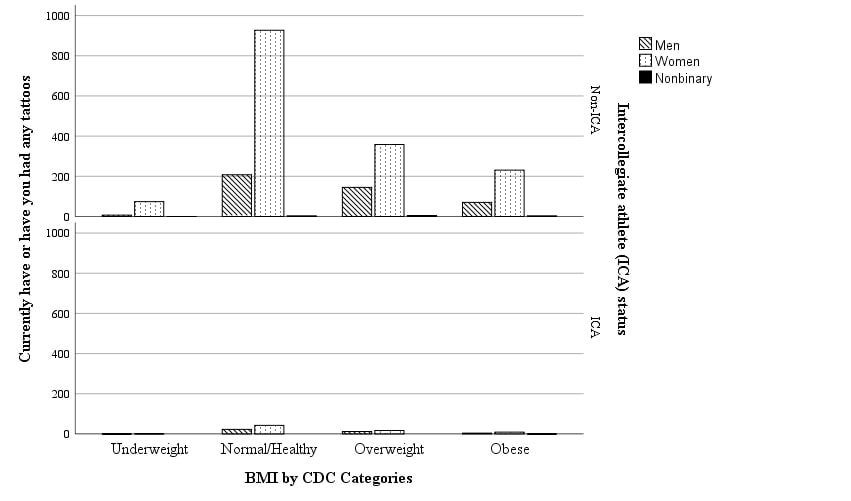

Do my tattoos make me look more fit, or fit at all? Gosh, I hope so. Look over here at my guns—er, arms---and not at the middle age gut I’m fighting to suck in. In a study of 6528 undergraduates we conducted nationwide, we found that tattooing may be used by those who are generally more fit, especially among men, to highlight that fact. There is extensive ethnographic literature suggesting that tattoos are signs of status and social roles. They indicate marital status, age, success in life, affiliation, and so on. But contemporary tattooing seems so dispersed and idiosyncratic—do those same motivations still apply in today’s world? In 2012, Rachael Carmen, Mandy Guitar, and Haley Dillon suggested tattoos (and piercing, but we’ll come back to that) fit two evolutionary patterns of behavior—these body modifications may indicate our affiliations with successful groups or injure our bodies so we can heal and show off our healthy immune systems. In 2016, Cassie Medeiros and I wondered if media portrayals of tattooed athletes amplified that signal out of proportion—in other words, are there really so many tattooed athletes or do they just get the most press: ...Or both, in a positive feedback cycle? ...Or are fans more likely to get sports tattoos? After all, athletes at the intercollegiate or professional level are already obviously highly fit people, for the most part, and being recognized for such through through athletic performances---especially if they win! Maybe it’s the folks who aren’t on the teams getting all the ESPN attention who need to shout, "Hey look at MY hot bod!" Or, "Yes, I AM the 12th (hu)man responsible for the decade of football success at the Alabama, as you can see from my 'Roll Tide' tattoo." We tested these hypotheses in two online studies, asking undergraduates if they were tattooed, pierced, athletes, had any college or pro sport-related tattoos, and had ever had any related medical complications. The first study was a national study of 524 respondents but was inconclusive because of the low number of intercollegiate athletes who responded. For the second study, we surveyed all 31,000+ University of Alabama undergraduates and received 6004 usable responses, including 50% of UA’s 572 student athletes and 31 of our national championship (ahem, repeated championship) football team. Here's what we found:

Article Accepted Regarding Tattooing Among Intercollegiate Athletes and Other Undergraduates9/19/2018 In writing our chapter "Tattooing, Commitment, Quality, and Football in Southeastern North America" for Evolution Education in the American South, Cassie Medeiros and I hypothesized that tattoos would be more common among elite athletes to highlight their fitness or among non-athletes who were fit as an alternative way to advertise fitness (besides being an elite athlete). Our HBERG team then tested this using the Body Art Study Questionnaire (Mayers et al., 2002) via first a nationwide internet survey among undergraduates, then a survey of all 31,000+ University of Alabama undergrads. The first survey elicited around 600 responses but very few tattooed athletes among them. The repeat study elicited around 6500 responses and a full 50% of the UA intercollegiate athletes.

The article summarizing these findings, "Shirts or skins?: Tattoos as costly honest signals of fitness and affiliation among US intercollegiate athletes and other undergraduates," has been accepted by Evolutionary Psychological Science and is current in press. Several people worked on this project over the years, but the authors who ultimately pulled this together include Taylor Puckett (cleaned and set up data codebooks), Nick Roy (cleaned data, helped with analysis, and edited paper), and Mandy Guitar (developed the hypothesis we tested in Carmen et al. [2012], and edited paper). We're grateful to work done along the way by Connor Fasel, Kat Beidler, and Kira Yancey, as well as the title idea by Rob Else. We are allowed to provide an Author's Accepted Manuscript here for preview. Our findings were consistent with the Human Canvas Hypothesis (Carmen et al., 2012), an evolutionary hypothesis that suggests tattoos advertise fitness or affiliation:

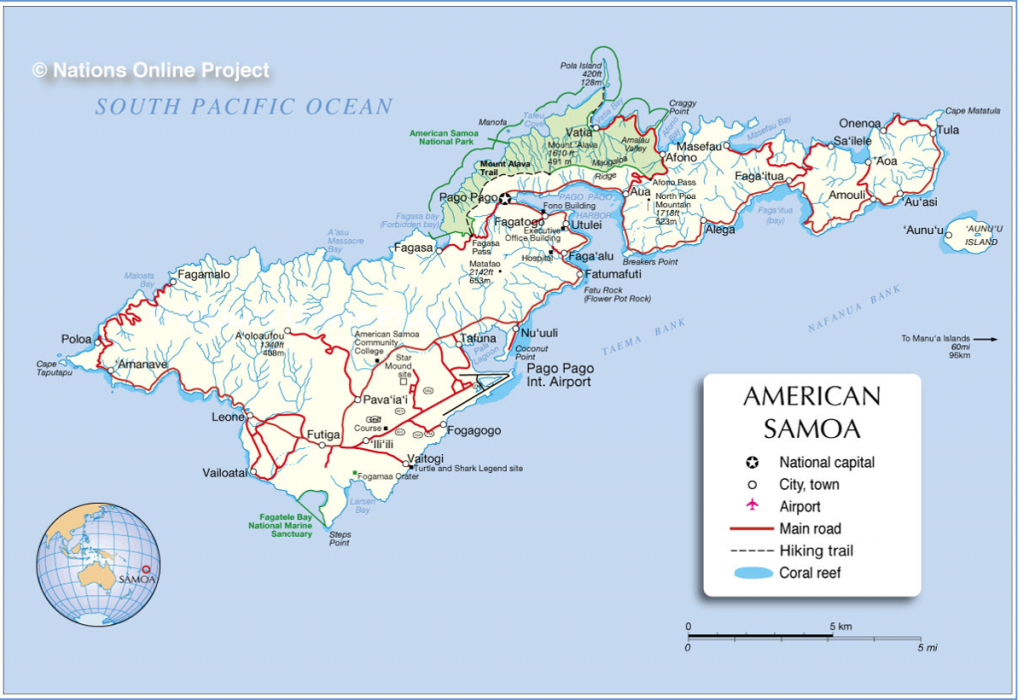

To learn more, read our AAM here. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We were scheduled to start data collection with Chilo and the malu at 11AM in Pago Pago, with Joe at Off Da Rock in Nu’uuli at 1PM, and with Su’a Wilson in Leone at 3PM. In theory, we could have been stretched much further. The island is not that big, and there is only one road, but the speed limit is only 25 mph, and we’d have been truly screwed to have collecting even two sets of data if they were at complete opposite ends of the island. As it was, we never went past Pago Pago or Leone this trip, but it would take at least 30 minutes to make this trip, so we needed to time things right. Things would inevitably change. And they did. First, we called Chilo to confirm the time of the malu and got no answer. Chilo had given his wife’s number on Monday when his battery had been dying, and I had kept it, so I called her. I asked if he was available, and she said, no, he is at work. At work? Isn’t he supposed to be starting a malu. So we drove to Family Mart, and I looked for but could not find him. I asked the clerk at the register, and she said he was butchering meat. I wandered around till I found him, butcher’s apron on, putting cuts of fish in the store freezers for sale. He greeted me and told me that the malu was delayed until 1PM. He did not get my calls because reception was poor in the freezers. I asked how he would get there, and he said he would either take an aiga bus (what they call the rickety private buses used for public transportation) or the family would get him on their way to his house from Leone. The whole family of the girl getting the malu, of course, would be accompanying her and, in fact, had arranged things with him. First, I thought to volunteer to pick him up and drive him, but then I knew this might make coordinating the other two tattoos difficult, so I promised to call him at 12:30 to make arrangements. I left somewhat aggravated but accustomed to such changes and delays. Off Da Rock was delayed as well, though not as much. Joe was building a shop for his wife in the house next door and was frequently running around picking up materials before an appointment. When he arrived for an appointment, he would still need to go back and forth to manage workers in the house while also tattooing and managing his business. He is the only tattooist in his shop and managing many affairs. He and his wife also run a morning workout for the community that starts at 5AM every morning, are officers with the National Guard, are financial advisers, and design and sell clothes on the internet and out of his shop until hers is finished. Plus they have two young daughters and, like all good Samoans, attend church regularly and are active members of their villages. Joe handles all the fa’alavelave obligations for his family rather than send to his parents in the mainland for remittances. Fa’alavelave are the obligations that interfere with normal life and call for special activities or celebrations, such as funerals, weddings, granting of matai titles, births, birthdays, and so on. Joe’s uncle a few homes over is the village high chief. We had collected enough data at Off Da Rock that we were able to get the first sample and anthropometrics from Joe’s client, then drive to Pago Pago to meet Chilo. We had to leave Joe and the client with the post-test saliva collection tube and instructions on how to collect the saliva. Apparently, we neglected to tell them how to take the collection straw off the tube and screw the cap on, as we recovered the sample the next day lying on its side, wrapped in a paper towel, with some of the sample dribbling out. There was enough still in the tube to use, but the devil of data collection, like so much, is in the details. We drove to Pago Pago, and I had to drop Michaela off with materials for collecting demographic info and saliva, along with good cameras we had borrowed from the American Samoa Historic Preservation Office. A malu would take more than one day, so we planned for me to take the hand dynamometer and bioimpedance analyzer to collect data at Su’a Wilson’s tap-tap session and collect body density and handgrip strength from Chilo's client later today when I returned for the balance of the session or tomorrow when we returned for the inevitable second session. I drove to Leone and asked Michaela to text me when she got picked up and their session started. The session in Leone started almost immediately. I barely had time to get set up and collect anthropometric data. Su’a’s stretcher, his son Mark, had them ready to go. I sat behind Su’a’s wife Reggie and watched as she fanned everyone, comforted the client, and chatted with everyone. The hours went by, no text. Finally, “still waiting.” That was both a relief and distressing. Su’a took 2 ½-3 hours to complete a tauvae or band around a girl’s ankle. It was her first tattoo, and her mother, who had grown up in American Samoa, had brought her to get it as part of her heritage. As I drove back to Pago, I texted Michaela. She was still waiting for Chilo but had tracked down his wife and was sitting with her. When I arrived, Michaela and Chilo's wife and their baby were sitting at the picnic table where we had talked to him and where I had left Michaela waiting 4 hours earlier. There was a half-eaten package of Tim Tams. I introduced myself then Michaela asked me to give them a few more minutes to talk alone. I wandered around for about 30 minutes until Chilo's wife left. Then Michaela told me to drive to a nearby Japanese place for dinner. Chilo was not doing a malu today after all, but he had another tattoo job and would be calling us. Does anyone at this point believe that he will be calling us or that he will doing any sort of tattoo? Neither did we, but we did eat nearby, if only to be able to process what was going on and get some food in us. After several hours of calling Chilo and having him say he was on the way, Michaela called his wife. The Samoan islands are very traditional and very gender stratified. One of Michaela’s cardinal rules of research there is that she will not form friendships with males. It is too fraught with gender disparities and opens everyone up to accusations of impropriety. If she must work with a male in some capacity, she goes to lengths to get to know the wife as well. So Michaela called Chilo's wife to forge a relationship, since she was allegedly going to be working in Chilo's studio without his wife present. Michaela’s instincts in this regard have been as accurate as her sense that she should bring a male researcher on—me—to be able to talk with high chiefs and other males in her primary research, the impacts of social inequalities on unwed mothers and their babies. American Samoa and Samoa still retain their traditional, male-dominated, village-based political structures for the most part and to varying degrees. They share the same culture and language but, for the past 100 years, slightly different colonial histories. In the early 19th century, missionaries took firm root on all the Samoan islands. It was just before and during this period that several paramount of high chiefs sought to extend their power over multiple islands, using European trade goods acquired by converting to Christianity toward these ends. It was through these political and economic pursuits that Samoan and colonial interests became entwined. It was the son of the first successful missionary who established copra as a trade item, which is dried coconut from which oil can be extracted. Flourishing copra plantations were established across the islands, especially the bigger and more agriculturally accessible Upolu. A German trading company moved in and monopolized this industry and was so successful that when the business failed in Europe, the German government bailed it out to retain the income coming from Samoa. However, German treatment of natives was poor and exploitative, and, in an effort to retain control of their own lands, chiefs in Tutuila sought protection from the U.S. government against German incursion by offering sole use of its prized deep sea harbor at Pago Pago. The U.S. resisted for some time but ultimately became embroiled in Samoan affairs and recognized the need to prevent German colonial expansion throughout the Pacific. A naval standoff between U.S., German, and British ships that nearly came to head was prevented by a sudden hurricane that scuttled nearly all the ships at anchor and killed hundreds of men, forcing a quick negotiation that resulted in the Germans holding Western Samoa and the U.S. Eastern Samoa, later named American Samoa. Western ended up in the hands of New Zealand after World War I, and then became independent in 1962. It changed its name from Western to Samoa in 1997, much to the consternation of American Samoans. American Samoa was managed by the U.S. Navy beginning in 1901. After several failed efforts to install kings of Samoa during the earlier colonial trade period, the U.S. opted to follow the German governing style of allowing Samoans to govern themselves at the village level as they have always done, through a hierarchy of selected matai and a government-selected mayor or pulenu’u. A gathering of representative chiefs or the fono met regularly to discuss issues with the governor, who for the first 50 years as a U.S. territory was a U.S. Navy officer, then an appointed U.S. politician sent to American Samoa, then, beginning in 1978, a native Samoan elected by Samoans.

Most people in the U.S. are likely unfamiliar with American Samoa and even the most educated would struggle to find it on a map. American Samoa is the southernmost U.S. territory and is closer to New Zealand and Australia than it is to the U.S. Its strategic purpose relative to, say, Hawai’i has always been limited and, thus, it is in many ways unsullied by modernization. On the other hand, American Samoa is as sullied a territory as there is in other ways. American Samoans having the ignominious distinction of being among the most obese peoples in the world. Samoans have been studied to death by scientists because of their interesting Polynesian ancestry and large phenotype. Aside from the high rate of obesity, Polynesians in general and Samoans in particular are a large-bodied people. Samoans are much sought after as American football players and New Zealand rugby players. Yet because of modernization and a switch, especially in the less agricultural islands of American Samoa, to reliance on trade and, more to the point, U.S. subsidies and aid, American Samoans have transitioned to diets of commodity foods high in calories and low in nutrients and suffer high rates of the diseases of civilization, including obesity, as well as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease. When we dig down a little deeper then, we come back around to John Enright’s noir depiction of the American Samoa Michaela invited me to help study last summer. When a society is highly patriarchal, highly Christianized, and is almost completely reliant on U.S. aid, NGOs, and family remittances, what social group is at the bottom of society suffering the most? Poor women, women with little family support, women with little family support and no husbands, women with children and little family support and no husbands. Of course, this is a synergistic type of situation, one created by the structure of the society as it has developed. Poor women are women without titles in their family. They have no access to village-level resources unless chiefs allot it to them. There are so many political and ritual obligations to become titled and among titled families that resources do not generally circulate much beyond them. Except when a fa’alavelave is held, and there are a lot of them. For each fa’alavelave, chiefs might demand that everyone in the community contribute, especially the family at the center of the celebration. So if a low-rank woman and man want to get married, their families are expected to pay lots toward the celebration. Of course they are also paying, like everyone, toward everyone’s celebrations, so it will take them a long time to have enough money to be able to get married. In the meantime—whoops—they have a baby. American Samoa has the worst condom education of any tribe, territory, or state in the U.S. Sex education is verboten because of their strong, conservative Christian identity and values. Which is a double-edged sword, since this young woman is now pregnant. So she gets in trouble with her village and her church and is literally ostracized from both. This is how she becomes the lowest echelon of society with the most suffering. Often, to save the family from shame, the woman will be taken to Samoa or the U.S. mainland to have her baby, which is then raised by a family member. Secrets are kept. Shame is hidden.

Which brings us back to Chilo's wife. She was mystified as to why he had told us he was doing a malu. He had never done a malu before. He didn’t do hand tap tattoos. He hadn’t done any tattooing in months. He worked so many hours a week at the Family Mart, he could not afford to take off the two days he told us he’d taken off to do the tattooing. He hadn’t told her anything of his plans to meet with us that day and never told her about his extracurricular activities, though he had told her of meeting with us previously and of our interest in his tattooing. He did seem to do tattoos occasionally, but they did not bring in much money and he needed to put in as many hours at Family Mart and ensure his job there. They were barely hanging on. She’d had two children by another man before him, a man now in prison. She couldn’t afford food for those children, so she tried to breastfeed them both and suffered maternal depletion syndrome. She liked how it made her so skinny and attractive, but it was not enough food for the children. They were starving, and her family told her she should take them to an aunt who could care for them. She used to visit them there more, but her aunt chastised them for showing the kids too much affection, as if she wanted them back. She had to pretend she was not their mother, so the aunt would continue to care for them. And now she and Chilo had this child to care for. She did not know why he had told us his studio was right across the way from Pago Plaza. He did not have a studio that she knew of, and they lived far up the mountain off the road. He called a few times throughout this conversation. No, the malu was not happening today. But another person had made an appointment with him. Stay there. He would be tattooing later tonight. We could come to the studio and see that tattoo, take photos. We had explained the entire study to him in words we thought he understand, had given him copies of the consent forms in English and Samoan. We had asked him if he understood and he’d said yes. But to his wife he said he didn’t know we wanted to collect saliva samples. He wanted us to take photos. He thought we were taking photos. He thought we were writing articles and would bring attention to his business. His wife explained to him and said his English was not all that good. She was not sure how much he could read or understand.

This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. Please consider contributing supporting the Inking of Immunity 2018 field season at Experiment.com/InkingImmunity. We had worried when the study started that we would have difficulty juggling multiple tattoo sessions with only two researchers because we only took along one bioimpedance analyzer (BIA). The study protocol is ultimately rather simple. It involves a short questionnaire about tattoo experience and some basic demographic information, then we collect hand-grip strength using a hand dynamometer, body density using a BIA, and a saliva sample right before the tattoo starts, noting the time, and another as soon as the tattoo concludes. From the saliva samples, we extract immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Immunoglobulin A is an antibody that lines the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract and is a frontline defense against common infections like colds and flus. Cortisol is a stress hormone that increases when the body or mind are responding to a stressor, like getting a tattoo. Part of the classic stress response involves turning off non-essential functions to deal with the source of the stress until the body can return to homeostasis, and the production of IgA is one of the things usually suppressed during stress response. But as we point out as part of our induction protocol, the body can become habituated to certain types of stressors and have mediated responses. Take exercise, for instance, which stresses the body and results in immunosuppression when a person is new to it. With regular exercise, the body actually becomes healthier and is better able to deal with the stress of it, as well as daily potential insults of other types. Unless one overdoes it. Studies of elite athletes find they catch upper respiratory tract infections more often than most and suggest it is due to fatiguing this system. There is a growing body of research that finds overtaxed stress response systems result in deterioration in the body, including cognitive deficits results from apoptosis in the hippocampus. We collect body density as an indicator of fitness and handgrip strength as indicator of underlying neurocompetence. By controlling for these—essentially equalizing people for these variables—we can compare tattoo experience to the changes in cortisol and IgA from the beginning to the end of the tattoo. In our previous research, we found that people with little to no tattoo experience responded to being tattooed with the predicted spike in cortisol and immunosuppression of IgA but that people with lots of tattoo experience did not have immunosuppression. In American Samoa, the logistic catch was that we had one dynanomometer and one BIA between us. Ironically, for much of the study, because there are so few tattooists in American Samoa, there were two of us hanging out for the entirety of a tattoo session when only one of us was necessary, and not even for the whole session. We really only needed to be there for the beginning and end, except for the need and want to collect ethnographic data. As it happened, the same day Chilo said he was doing a malu was the day Joe at Off Da Rock Tattoos had a client and Su’a Wilson was doing the first hand tap tattoo we’d been invited to collect data at. Finally, we had the luxury problem of having come all the way to American Samoa to collect as much tattoo data as we could in 6 weeks and had to juggle three at once. But why did we come to American Samoa? If there are so few tattooists, why not conduct this retest back in the mainland U.S., where there are more tattoo studios in any given town than there are McDonald’s and Starbucks combined (American Samoa doesn’t even have Starbucks, though they do have Starstruck—however, they have two McDonald’s, one of which has been the highest grossing McDonald’s in the world several years running). We came to American Samoa to retest the model because you can’t generalize a scientific finding from 29 mostly women in Alabama to much of anyone else, despite the elementary nature of the finding (this finding, though compelling to media, is consistent with basic stress response and allostasis theory but cooler when applied to culture and especially to tattooing). And we came because the Samoan Islands have the longest continuous history of tattooing.

The myth of the twin sisters who brought tattooing to Samoa is a story everyone knows, though there are different versions of the story. The most common version is known because of “The Samoan Tattoo Song,” which one can hear regularly on Samoan radio. https://youtu.be/wIgCNQeZYBA

As the song indicates, women brought the tattoo tools because tattooing was originally the realm of females, but they made some mistake and ended up switching things around. The longer myth deals with the families who were given the tools, which relates to the guilds that are allowed to teach and apply hand tapping now. Ausage also believes the story originally referred to Fiti, not Fiji, which is short for the village of Fitiuta, but that it has been distorted and confused with time. When the first explorers recorded to have sited Samoa landed, they thought the Samoans wore silk knickers because of their pe’a, which are the male tattoos extending from midriff to below the knees. To be continued… This narrative derives from field notes from the Inking of Immunity and Pepe, Aiga, and Tina Health Study (PATHS) in American Samoa. |

Christopher D. LynnI am a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alabama with expertise in biocultural medical anthropology. Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed